New York City’s designated truck routes are a site of disproportionate harm: More than 50 percent of fatal bike and pedestrian crashes between 2019 and 2022 occurred on truck routes, according to an analysis of city data — even though they account for just 13 percent of city roads. Amidst that ongoing carnage, recently proposed City Council legislation to jump-start a redesign of the network is long overdue.

It's not surprising that these high-traffic roads are so problematic for safety: They serve multiple purposes and users all at once, providing access to the adjacent workplaces, retail, residences, and parks that line their curbs, while also organizing a speedy flow of a vehicular traffic considered especially essential to metropolitan life — the near-last mile flow of freight. Traditional traffic engineers call these priority roads “arterials.” As a body needs blood, a city needs a flow of goods on trucks and people in cars.

Or so the analogy goes.

The truck network is also a product of city planning. New York City widened and reconfigured local roads to support the speedy movement of trucks in the 1950s and 1960s, under the claim that such changes would increase safety by limiting trucks to designated areas. Yet the unavoidable presence pedestrians along these routes was even planned-for at that time, such as when officials added park-like medians to Lower Manhattan’s Allen Street in 1957.

As the city continued to develop, many designated trucks routes became more dense with more mixed uses. Current open data shows that 55 percent of non-highway New York City truck routes pass through dense commercial, mixed-use, or apartment residential areas.

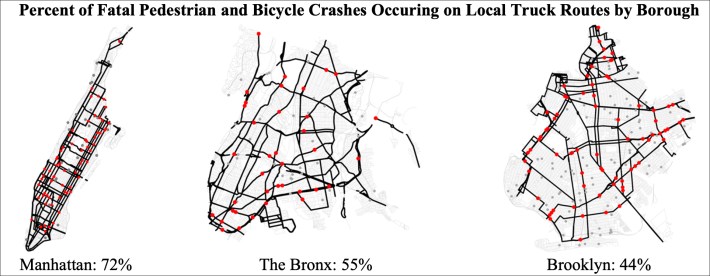

There are differences in truck routes among the boroughs, but the overall picture of disproportionate harm remains the same:

- In Manhattan, which has the highest density of truck routes, over 70 percent of its fatal pedestrian and bicycle crashes occur on truck routes, yet 69 percent of the borough's roads are lined with commercial or dense residential uses.

- In the Bronx, with the second highest density of truck routes, over 55 percent of fatal pedestrian and bicycle crashes occur on truck routes, while commercial or dense residential areas line 51 percent of its roads.

- And in the larger Brooklyn, which has the highest per capita pedestrian and bicycle crash rate in the city, 44 percent of fatal pedestrian and bicycle crashes occurred along truck routes, while commercial or apartment residential areas line 65 percent of its roads.

The problem is not just trucks themselves (which pose a particular danger to cyclists), but the prioritization of routes for high-volume vehicular traffic — including cars — in a transit, walking, and cycling city. Streets like Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue, the site of several recent crashes, become deadly for local pedestrians as a result.

Better design can improve safety. Interventions such as daylighting intersections, loading zones, and leading pedestrian intervals can and should be prioritized in areas with dense commercial or residential land uses along truck routes. Yet such interventions can be overwhelmed by traffic volumes, speeding, and oversized vehicles.

The challenge stems from a widespread (and equally misguided) belief that we need some non-highway urban roads to be wide, fast, high volume, and accommodating of large vehicles for the sake of our economy and our consumption. Lasting and just solutions therefore need to center on reducing vehicle sizes, traffic volumes, and practical speeds on non-highway truck routes and other major arterials. This can be accomplished through promoting forms of micro delivery, the restriction of oversize vehicles, better/automated enforcement of speeding, and widespread traffic calming. Robust investment in quality transit can also reduce the volume of cars clogging our truck routes. In Manhattan, congestion pricing will also help. Such reductions will also ease the task of more equitably distributing the environmental and health burdens of truck routes.

Does limiting the form and speed of goods flowing on our “arterial” roads damage the body — our city’s economy and our consuming lifestyles? Not necessarily.

If there is a premier tech-world art form of the 21st century, it is logistics. If local government shifts the rules of transportation toward keeping people safe, and collaborates with industry in doing so, tech talent will find a way to deliver goods in a reasonable time to shops and doorsteps. Such rule-setting in the interest of resident well-being is merely city government doing its job. Recent collaboration on piloting micro-hubs is an example of such a role.

After reconsideration, where large trucks are deemed needed, they can be allowed. But up to now, we have mostly let an assumption of the necessity of widespread large truck traffic dictate the pace and design of our most central mixed-use roads, with cars benefiting most of all. The renewed focus on truck routes is a chance to rethink that assumption.

Jonathan Stiles is an urban planning researcher and technologist residing in Brooklyn. He is a post-doctoral fellow with Florida Atlantic University and the Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety. A sample of the analysis and the data sources used in this piece can be found here.