Last year, 252 people died in city traffic, according to final NYPD numbers. That was 3 percent more than in 2019, the last year before Covid disruptions. Mayor Adams and the city Department of Transportation called that a victory, citing a drop of about 7 percent from 2021 and 15 percent from 2013, before the Vision Zero safety program began.

But 2021 was an abnormal traffic year for comparison, and a drop of just 15 percent in deaths after a decade of street-safety programs isn't saying much.

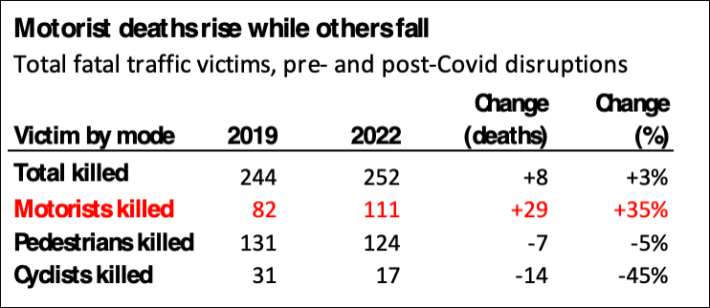

What the mayor could have said is that safety changes specifically to surface streets are working. NYPD data shows that speed cameras, intersection redesigns, road diets, bike lanes, and other interventions brought cyclist deaths down 45 percent in 2022 from 2019, despite the surge in people cycling. Pedestrian deaths dropped 5 percent, bucking a national trend. Traffic injuries overall, which are far more common than deaths, fell by over 11,000, or 18 percent.

The only category that got worse (see table) since the year before Covid was deaths of people inside cars, a tragedy for dozens of families as the victim count rose from 82 people to 111, up 35 percent.

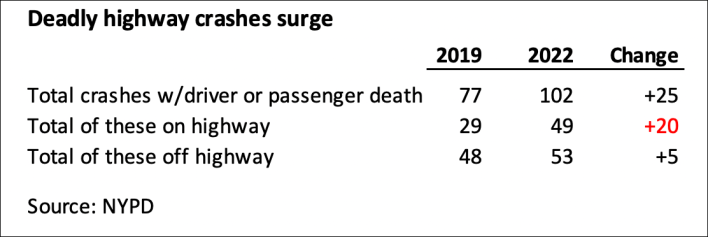

Location data on crash reports reveals that four out of five of the additional crashes that killed people in vehicles took place on highways, not surface streets, more than double the previous proportion. The worst routes were the Cross-Bronx Expressway and the Henry Hudson Parkway, each with five deaths.

The 49 fatal highway crashes in 2022 compare to just 29 in 2019 and were the only reason the total number of traffic deaths in New York rose at all. That's important, because highways are also the only type of New York roadway not to have received major new safety redesigns or speed cameras in the past several years.

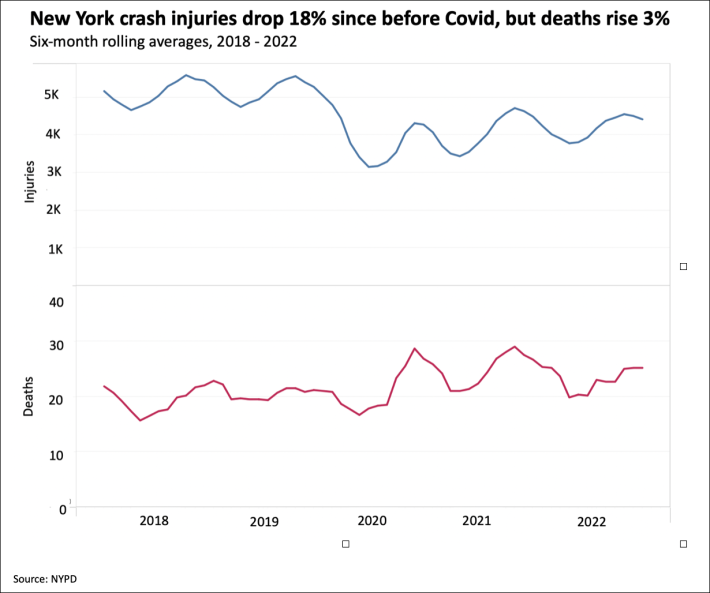

When deaths are up but injuries are down (see graph below), and when the incremental deaths are unusually concentrated on highways, it means fewer collisions overall but more severe ones at high speeds. The speeding likely relates to work-from-home arrangements, with fewer cars on the road than before, at less-concentrated times of day. Less congestion correlates in general to greater speeds and higher crash rates.

What the data tell us overall is that the city is on the right track (even if slow) with safety improvements to surface streets, but that highways need urgent attention. None of the urban toolkit of narrowed lanes, pedestrian refuges, upgraded crosswalks, tighter turning geometry, leading-pedestrian-interval lights, bike lanes, daylighting, or speed humps applies to them.

Unfortunately, the most proven tool for reducing the most violent crashes — control by speed cameras — is not allowed by New York State on the city's highways. That's outrageous, given the way the crash data is trending.

If Mayor Adams wants to stop having to explain away horrific traffic-fatality results with comparisons to a decade ago, he should keep pushing Albany for speed cameras on highways and arterials. In the meantime, he should resist critics who want to roll back or block surface-street improvements. The safety toolkit works well where it's allowed to.

Stephen Graham is on the adjunct faculty in Urban Planning at NYU Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. He also teaches MBA students at NYU Stern School of Business and was a director of US and Latin America research at Citigroup and Goldman Sachs. He can be found on Twitter as @ForwardBike.