The MTA Needs to Stop Saying it Doesn’t ‘Need’ Congestion Pricing Money: Advocates

4:01 PM EST on November 23, 2021

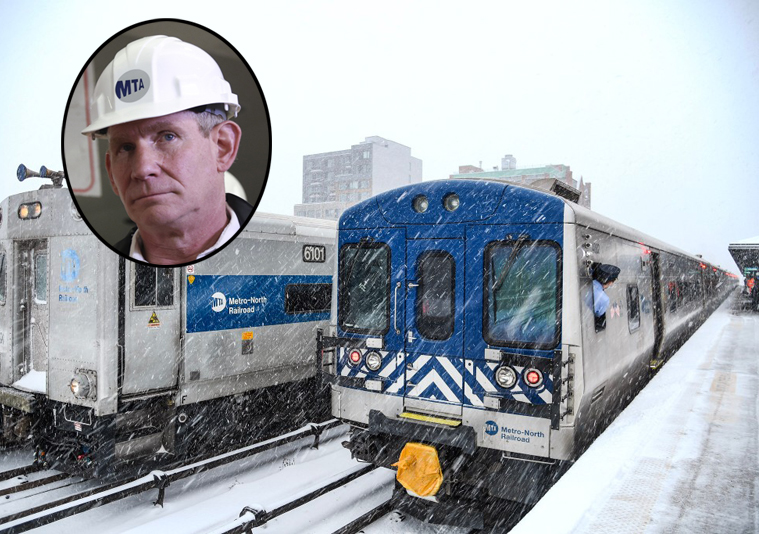

The MTA desperately needs congestion pricing money, though CEO Janno Lieber (inset) doesn’t think so yet. Photos: MTA

It's a capital offense.

The MTA's spending on big-ticket repair items that are vitally needed to keep the transit system operating has slowed alarmingly, thanks to the delay in congestion pricing and the affect of the Covid-19 pandemic — and the agency isn't helping itself by continually saying that it doesn't yet need congestion pricing revenue, watchdogs said on Tuesday.

Multiple factors are creating an imperfect storm for the agency's failure to get its 2020-24 capital plan firing on all cylinders — not to mention finish allocating funds for a handful of still undone projects from the 2015-19 capital plan. Those factors include the Covid pandemic and delays in congestion pricing, which the MTA had once said would be funding repairs in 2021 (now mid-2023, which itself is optimistic).

Nonetheless, MTA CEO Janno Lieber raised eyebrows at a state Assembly oversight hearing on Thursday by saying that the green tide of tolling revenue is "not urgently needed" yet because the purpose of MTA's capital wish list is simply to "get all the contracts awarded in the five-year period," even if work doesn't start (i.e. the money itself isn't spent) for many years. (Roughly 8 percent of the contracts in the current five-year capital plan — which is about to enter its third year — have been awarded, the MTA said.)

Congestion pricing was expected to provide about $15 billion in bonds to fund the $54.8-billion package, but is currently providing zero. The MTA recently hyped its success in gaining billions in federal funding under the recent infrastructure infrastructure bill that President Biden signed last week, but it will not replace lost congestion pricing revenue "because the MTA already budgeted for the federal funds," the watchdog group Reinvent Albany previously said in a statement.

Lieber estimated that the global pandemic delayed the issuing of contracts by a year to a year-and-a-half. And to show how unconcerned he was, Lieber also revealed that 10 to 15 percent of contracts from the 2015-19 capital program have not even been awarded yet.

One advocate for robust capital funding, Ben Kabak of the blog Second Avenue Sagas, publicly blanched at Lieber's suggestion that congestion pricing money isn't urgent. While technically true that the MTA would not be spending toll money yet, even if it was coming in, Kabak suggested that pretending the money wouldn't be immediately valuable is a bad look.

"I am begging MTA leadership to avoid giving CP opponents more ammunition. I mean, I get Lieber's point and it undergirds their slow review process. But come on," he tweeted. "Plus, we need congestion pricing to slow down congestion."

Liam Blank of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign had a similar take.

"They are leaving billions on the table by not implementing it as soon as possible," said Blank. "Besides, congestion pricing is about addressing issues that are long outstanding, such as accessibility, public health from pollution, and the climate crisis. It's more than just revenue."

Meanwhile, the watchdogs at Reinvent Albany are especially concerned about the slowing pace of repairs. In August, the group sounded the alarm that the MTA had gathered just $2 billion for the $55-billion capital plan, slower than it had set aside cash for the previous two capital packages. By last week, according to the MTA, that number had risen to about $4 billion, but nearly $3 billion came from the federal government.

On Thursday, the group also pushed back on Lieber's comments.

"Funds for the 2020-2024 plan have come in at the slowest pace of the last three capital plans. This trend has continued," Rachael Fauss, the group's senior research analyst, testified. "Dedicated revenues like congestion pricing are essential to the survival of the MTA given its high debt loads."

Lieber says "congestion pricing funds are not urgently needed," because capital plan actually doesn't get done in five years. "The goal is to get all the contracts awarded in the five year period," he says. "Our five-year plan has been pushed out by 12-18 months during COVID."

— David J. Meyer (@dahvnyc) November 23, 2021

Fauss told Streetsblog that her group definitely does not like the rhetoric coming from Lieber (and before him, CFO Bob Foran) about congestion pricing.

"The MTA said they don't need the money, but yes, yes they do," she said. "Money now is better than money later. There are no other sources of money in a meaningful way. If that money started coming in in 2021, they could start bonding right away."

That's one reason, Fauss said, that the MTA only spent $2.7 billion in the first half of 2021, compared to $6.2 billion in 2020 and $7.3 billion in 2019. Part of that is due to the Covid shutdown, but delays cost money and make the work less likely to be done. (The 2015-19 capital plan, originally budgeted at $29.4 billion is now on pace to cost $33.4 billion, according to the MTA's own dashboard; and even the 2020-24 capital plan is costing more, from its original $54.321 billion cost to the current $54.366 billion, a not-insignificant increase of $44.8 million, according to the same dashboard.)

"They are proceeding at a slow pace compared to prior plans — and this is a bigger plan," Fauss said. "In the 2010 plan, there was some Hurricane Sandy work that still hasn't been finished and maybe that would have helped with Hurricane Ida."

Congestion pricing is not technically delayed, at least from the perspective of the MTA's timeline. But experts long said that both the Trump administration and the Cuomo administration slow-walked the required environmental impact assessment while in office. The current timeline suggests that tolling revenue will start coming in by mid-2023 — but even that's optimistic, given mounting efforts to delay or even kill congestion pricing, or to create so many exemptions (firefighters! Cops! Manhattan residents who make as much as $100,000! New Jersey residents!) that the program doesn't raise enough money.

So saying they don't need the money is a bad strategy for MTA officials.

"It's a general problem that the MTA’s has not advocated for itself well enough," Fauss said. "Going to he feds and asking for money is easier than going to the governor — especially the last governor — and asking for money, especially when you are asking for money from things like taxes and tolls."

MTA spokesman Aaron Donovan offered a general comment about the advocates' concerns.

“The pace of committing projects from the 2020–2024 capital program, like all capital programs, is determined by many factors, including the complexity of the specific projects and the overall funding mix of such projects," he told Streetsblog. "The five-year capital program period is designed to provide for the initiation of projects, which cashflow over a period of years after the commencement of work.

"The question about the timing of introducing a bond credit secured by [congestion pricing] revenues contains an embedded assumption that this can begin immediately after the initiation of the program," he continued. "This is the first toll program of its kind in the United States and there are no direct comparable transactions, which is of significance to market participants such as rating agencies and investors. MTA and the Triboro Bridge and Tunnel Authority have stated that in order to successfully bond against [congestion pricing] revenues, the program needs to demonstrate successful revenue collection for approximately 12-18 months to demonstrate a baseline revenue stream and further, critical possible extraneous issues need to be resolved (e.g. legal challenges to the toll, legislative or other political efforts to modify the program, etc.) before a credit is introduced to the market. MTA and TBTA have also stated that toll revenues will be made immediately available to the capital program as PayGo funding prior to the introduction of the [congestion pricing] credit.”

Gersh Kuntzman is editor in chief of Streetsblog NYC and Streetsblog USA. He also writes the Cycle of Rage column, which is archived here.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog New York City

Friday’s Headlines: Canal Street Follies Edition

Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine isn't happy. Plus other news.

Daylight Again: Bronx Community Board Backs Parking Ban at Intersections

The Boogie Down is down with daylighting!

Community Board Wants Protected Bike Lane on Empire Blvd.

Brooklyn Community Board 9 wants city to upgrade Empire Boulevard's frequently blocked bike lane, which serves as a gateway to Prospect Park.

The Brake: Why We Can’t End Violence on Transit With More Police

Are more cops the answer to violence against transit workers, or is it only driving societal tensions that make attacks more frequent?

Report: Road Violence Hits Record in First Quarter of 2024

Sixty people died in the first three months of the year, 50 percent more than the first quarter of 2018, which was the safest opening three months of any Vision Zero year.