This is the fifth installment of our feature: “What will the next Manhattan DA do about reckless drivers?” Earlier features included an op-ed by candidate Liz Crotty, which advocates for decriminalizing reckless driving, and a counterpoint op-ed by challenger Assembly Member Dan Quart calling for stiffer penalties for drivers who injure, maim and kill. Another candidate, Diana Florence, argued for the establishment of a vehicular-crimes task force. while a fourth, Tali Farhadian Weinstein, applied public-health insights to traffic violence. Today’s feature is by Lucy Lang, another candidate in the June 22 primary to replace outgoing DA Cyrus Vance Jr.

As the city comes alive again after COVID-19, the growing numbers of cyclists, runners, and pedestrians to our parks and streets are a welcome sight and testament to the resiliency of New Yorkers. Yet the more than 200 traffic deaths and 2,500 serious injuries of vulnerable road users — a trajectory that looks worse in 2021 — are a stark reminder of our city’s failure to grapple with traffic violence despite city efforts like Vision Zero. We deserve better.

Anemic, under-enforced, and overly driver-protective laws and a culture that too often blames victims make it easy for reckless drivers to escape anything more than minor consequences and any real accountability. As a former Manhattan assistant district attorney, I spent years leading violent-crime investigations and working with the families of victims to seek justice and accountability. I’ve witnessed the devastation that violence causes up close — not just to victims and their families, but to entire communities.

The reality is, traffic violence should be treated like other violence. That starts with enforcing the traffic laws we have on the books, and doing an independent review of any crash that results in serious injury, with public documentation of the review where legally permissible. It means holding those who commit violence accountable, and working to stop it before it occurs.

During a recent ride through upper Manhattan, I spoke with livable-streets advocates about the tensions between traffic enforcement and criminal-justice reform. In a country that is struggling to reckon with mass incarceration, how do we combine justice and better resolution for traffic-violence victims without resorting to harsher penalties or more incarceration?

New Yorkers should not have to choose between ending mass incarceration and safety: We can achieve both. One place to start is in the use of restorative justice — an alternative response to crime with origins in indigenous peoples’ cultures, that prioritizes healing, accountability, and the needs of the crime survivor. I am deeply committed to expanding the use of restorative justice at the Manhattan DA’s office and believe that — used appropriately and in consultation with victims and families — it can be the right solution in a meaningful number of cases, including those involving traffic violence.

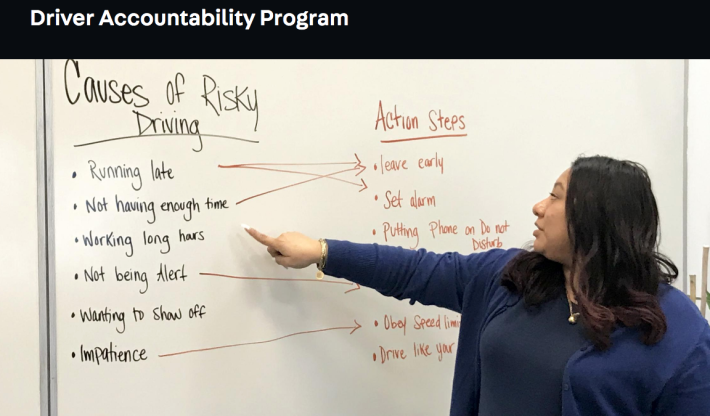

One such model has in part been piloted since 2015 through the Driver Accountability Program at the Red Hook Community Justice Center and has expanded to every borough except Queens. In the DAP, drivers participate in group discussions that incorporate the voices of victims (although they do not directly speak with the victims of their crimes). The discussions and other exercises force drivers to reckon with the harmful beliefs and behaviors they've brought behind the wheel. The program works: Preliminary findings show a 40 percent reduction in rearrests for traffic-related offenses, and 89 percent of respondents reported a change in driving behaviors in a post-program survey.

The time is right to expand the DAP and include a component in which drivers directly face their victims and/or the families of their victims for these serious crimes in a facilitated conversation called a “victim-offender-conference.” VOCs are a well-studied restorative-justice tool that reduce offender recidivism and promote resolution for victims. The wellbeing of survivors and of victims’ families must always be a top priority, and VOCs have been shown to be effective for victims, especially at lowering clinical rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Of course, VOCs alone will not always be enough to address traffic crimes, and should be combined with license suspension or revocation, indirect reparation (such as community service), and incarceration for the most serious crimes. An approach that offers to take incarceration “off of the table” in return for agreeing to non-incarceration penalties (such as license suspension) combined with a VOC gives offenders a choice to own up to their behavior and truly reckon with the harm they caused. Such de-escalation allows for a more positive and, ultimately ,just resolution to terrible moments of violence and tragedy. Even better: We could combine restorative practices with enforcement programs such as the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program. Requiring repeat offenders caught by automated enforcement to participate in restorative approaches could prevent serious injuries — by forcing the worst drivers to face the potential consequences of their actions, not simply pay a fine and move on.

VOCs will not be right for every case and must be deployed intelligently and sensitively by trained District Attorney’s Office staff. I’m running to be the next Manhattan DA in order to shift the culture of the office toward a community-centered approach to law enforcement, guided by what creates the best community outcomes, not by a focus on retribution. We must fairly and consistently enforce the law in a way that prioritizes harm reduction and resolution.

As the city transitions from a focus on automobiles to become more friendly to alternative transportation, we will wrestle with the cultural conflict between the city we are and the city we want to become. We will successfully navigate the shift only through community-centered approaches to changing rules, laws, and culture around traffic and traffic violence.

Lucy Lang (@LucyLangNYC) is a candidate for Manhattan district attorney, a former Manhattan assistant district attorney, and recent director of the Institute for Innovation in Prosecution.