“Live long enough,” the saying goes, “and you’ll see everything.”

So it is. On Friday, we saw perhaps the first-ever NY Times link to “Banning Cars from Manhattan,” the seminal 1962 samizdat essay that suggested another urban world was possible. We also saw a 3,000-word essay revivify the truths in the classic 1980s underground sticker, “Ban cars from the city: They pollute, they kill people, they take up space.”

All this, and more, in a piece provocatively titled, "I’ve Seen a Future Without Cars, and It’s Amazing" by Times opinion columnist Farhad Manjoo — with a subtitle that dared to ask, “Why do American cities waste so much space on cars?”

To paraphrase jazz immortal Sun Ra, space is place for us urbanists. To me, what makes Manjoo’s essay so distinctive is its focus on the immense space cars and driving require. That, plus its conviction that New York and other cities can and must be transformed, now — during and post pandemic; plus that it appeared in the New York Times, automatically giving it currency and gravity.

Space — the word — appears 19 times in the essay. Its close cousin, land, shows up for 15. “If cars are our only option, how [after the pandemic] will we find space for all of them?,” Manjoo muses. Cities’ “worst mistake [was] giving up so much of their land to the automobile,” Manjoo declares:

Automobiles are not just dangerous and bad for the environment, they are also profoundly wasteful of the land around us: Cars take up way too much physical space to transport too few people. It’s geometry.

Cars wasting space is old hat to anyone who spends much time biking in New York City. And the hopeless geometry of cars in cities has been a thing on “Transit Twitter” for some time. But I’ll bet Manjoo’s message struck Gray Lady readers as fresh and new. Even if they’re now schooled in tailpipes and carbon and crashes, most “normies” probably haven’t thought that “as roads become freer of cars, they grow full of possibility.”

Manjoo is speaking to this car-cocooned majority, sagely anticipating their objections and trying to help them get over, with passages like this:

What’s that you say? There aren’t enough buses in your city to avoid overcrowding, and they’re too slow, anyway? Pedestrian space is already hard to find? Well, right. That’s car dependency.

Without cars, Manjoo explains, “Manhattan’s streets could give priority to more equitable and accessible ways of getting around.” Crucially, these better ways aren’t ride-hails or Teslas or self-driving cars. Indeed, one of the essay’s notable feature is its kiss-off to digerati fantasies of melding technology, automobiles and cities. (Manjoo, a former reporter, covered Silicon Valley.)

No faux disrupter, Manjoo is going sustainable and long, urging bike superhighways and bus rapid transit and congestion pricing and ample sidewalks — elements of a wholesale repurposing of the vast space taken up by moving cars, parked cars, cruising-for-parking cars, stuck-in-traffic cars, refuel stations and the like.

In Los Angeles, “land for parking exceeds the entire land area of Manhattan, enough space to house almost a million more people at Los Angeles’s prevailing density.” And just in Manhattan, “nearly 1,000 acres ... is occupied by parking garages, gas stations, car washes, car dealerships and auto repair shops.” (Central Park covers 840 acres.)

“The amount of space devoted to cars in Manhattan is not just wasteful, but, in a deeper sense, unfair to the millions of New Yorkers who have no need for cars,” Manjoo writes, before teeing up this killer quote from urban planner Vishaan Chakrabarti: “It really does feel like there is a silent majority that doesn’t get any real say in how the public space is used.”

Chakrabarti, whose Practice for Architecture and Urbanism firm provided underpinning for Manjoo’s column, here joins the Regional Plan Association in demanding that politicians stop coddling the pro-car NIMBY’s who overpopulate city community planning boards and problematize virtually every measure that might take space from cars.

“Cars aren’t just greedy for physical space,” Manjoo writes, “they’re insatiable,” calling out the true meaning of induced demand: “an unwinnable cycle that ends with every inch of our cities paved over” (an outcome sadly familiar to aficionados of Streetsblog’s Parking Madness tournaments).

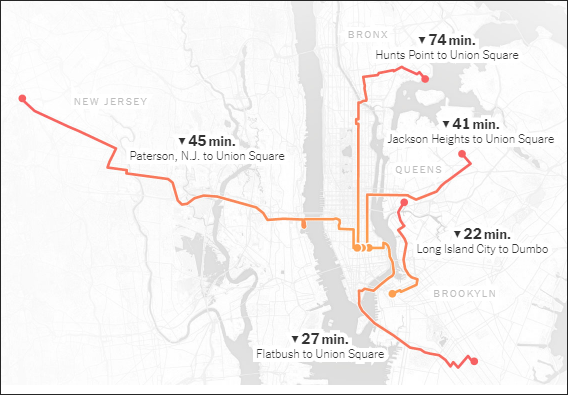

“Cars make every other form of transportation a little bit terrible,” Manjoo adds, perhaps understating. “The absence of cars, then, exerts its own kind of magic — take private cars away, and every other way of getting around gets much better.” That goes for walking, biking, scootering, even taxis and Ubers, Manjoo notes, but, above all, for buses, as Chakrabarti’s graphic of time savings from removing Manhattan car traffic makes clear.

I posted that graphic on Twitter in response to concerns that barring most private autos from Manhattan and upgrading bus service to BRT, as Manjoo suggests, “wouldn’t serve equity.”

“On what planet,” I asked, “is cutting super-double-digit minutes off bus commutes in/around NYC not a win for equity?”

Of course, a win for equity like humane and efficient buses is a poor stand-in for an across-the-board commitment to equity, as was pointed out in response.

“A true commitment to equity changes the power structure for making decisions,” added another commenter — and I fully agree.

But I don’t think it’s helpful to fault Manjoo’s article, or their vision, for failing to confront power structures that enforce economic inequality or white supremacy. Dismantling those structures is the paramount work of our time, in my view. And I want no part of any measures that would further entrench them. Yet making New York and other cities safe, sustainable and habitable for their hundred million or more inhabitants is also vital. I’ve seen nothing suggesting that aggressively reducing car dependence along the lines urged by Manjoo will either interfere with that work or worsen conditions for communities of color and other underserved constituencies.

The 2021 races for mayor, public advocate, comptroller and city council are fast approaching, and Manjoo has sent NYC livable-streets advocates a clear signal to elevate our game. The signoff from their column gets the last word (emphases added):

Many of the most intractable challenges faced by America’s urban centers stem from the same cause — a lack of accessible physical space. We live in a time of epidemic homelessness. There’s a national housing affordability crisis caused by an extreme shortage of places to live. And now there’s a contagion that thrives on indoor overcrowding. Given these threats, how can American cities continue to justify wasting such enormous tracts of land on death machines?

How, indeed?