Carolyn Konheim, a pioneer of the movement to reclaim New York and other cities from the automobile, died last Monday. She was 81. Carolyn’s public profile dimmed during the long illness preceding her death, but her legacy is large and lasting.

As a young Upper West Side mother circa 1964, Carolyn was constantly brushing soot flakes off her sons’ snowsuits when they played in Riverside Park. Alarmed and aroused, she teamed with her neighbor, budding ecologist Hazel Henderson, to form Citizens for Clean Air, one of the nation’s first anti-pollution groups and perhaps the most seminal.

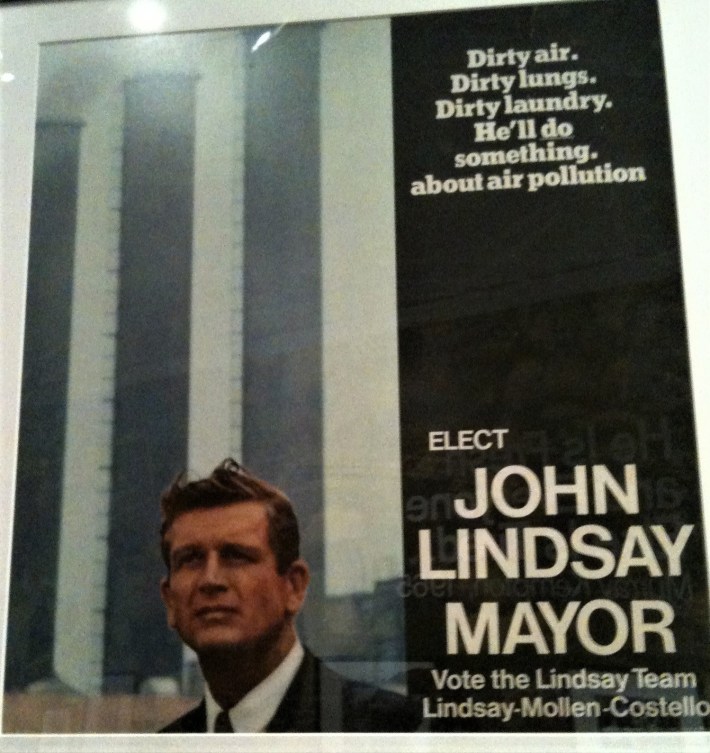

Befitting their name, Citizens for Clean Air unshackled urban air pollution from engineering esoterica and placed it on the agenda of ordinary citizens. Pollution was not a concomitant of progress but a policy failure to be cured by public mobilization and government action. Responding to this rising tide, then-Rep. John Lindsay added clean air to his 1965 mayoral campaign platform. “Dirty air. Dirty lungs. Dirty laundry. He’ll do something about air pollution,” read a Lindsay campaign poster (below).

The clean-air movement made sure Lindsay kept his word. In 1966, his first year as mayor, he outmuscled Big Oil and won legislation slashing seven-fold the sulfur content of the heavy oil that fueled New York’s power stations and steam system. Emissions of sulfur dioxide and particulates plummeted, the first major step in abating New York’s air pollution, and a reprieve for vulnerable seniors and kids.

Half-a-dozen years later, facing a low-sulfur oil shortage, Lindsay’s EPA, stocked with battle-hardened eco-zealots like Carolyn, conditioned a temporary variance to burn cheaper dirty oil on a sulfur surcharge that taxed away the added profit. The sulfur tax kept city buildings warm and illuminated without fouling the air. (My lifelong passion for “externality pricing” started with this elegant win, which I witnessed at close range as a junior economist at city EPA, later renamed the Department of Environmental Protection.)

By then, Carolyn had joined the Lindsay Administration as head of communications for the EPA’s Department of Air Resources. I can’t vouch that she was “in the room” when the dirty-oil surcharge was conceived, but during her tenure, Carolyn oversaw a variety of “stationary source” air pollution controls that largely did away with the soot that had been raining on her kids’ clothing.

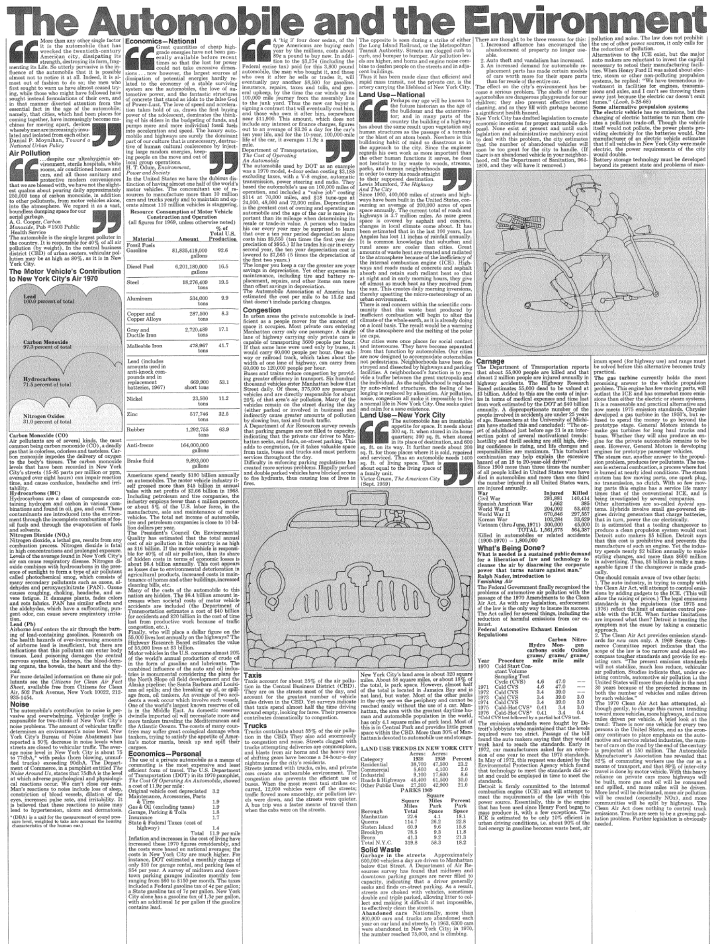

Before long, Carolyn’s attention at city EPA turned to two new matters: urban damage from the city’s ever-expanding plague of cars and trucks, and Air Resources’ renegade automotive engineering genius, Brian Ketcham.

Here, Carolyn’s story begins to intertwine so thoroughly with Brian’s that it is impossible to separate the two. Brian and Carolyn fell in love, dissolved their respective marriages and eventually married. They also synergized their professional expertise — Carolyn’s in writing, policy analysis, coalition building and citizen participation, Brian’s in tailpipe pollution controls, traffic engineering and transportation planning. Their collaboration would blaze paths still being trod by today’s livable streets advocates.

Consider city EPA’s Transportation Control Plan — Brian’s groundbreaking set of stratagems to elevate city air quality to “healthful” levels by downscaling driving in and around Manhattan. When clubhouse pol Abe Beame replaced Lindsay as mayor in 1974, and with the city in deep recession (set off, ironically, by an oil price shock caused by overuse of gasoline), central elements of the plan such as tolling the East River bridges, replacing taxi cruising with cab stands, creating exclusive bus lanes and expanding transit funding fell by the wayside. All would be exhumed (some in different guises, e.g., bridge tolls reincarnated as congestion pricing), but only after a revolution had taken hold in the way we understand cars and cities.

The crucible for this revolution was Westway — the mammoth scheme to replace the collapsed West Side Highway with an underground superhighway topped by massive real estate development. Westway’s government and business backers packaged the interstate-grade highway as a way to unsnarl city streets and clear the air, but Carolyn and Brian, virtually alone, saw it as a taxpayer-financed swindle that would worsen traffic and pollution by making it easier for more cars and trucks to be driven into and through Manhattan. Steadfast and magnetic, Carolyn gradually won adherents to the anti-Westway cause with both the specter of “induced demand” and the promise of “trading in” Westway funds for mass transit (an option she helped write into federal highway legislation).

That Carolyn and Brian eventually prevailed on non-transportation grounds — federal and state government’s dismissal of Westway’s impact on the Hudson River fishery was deemed a violation of the National Environmental Policy Act — in no way diminishes the magnitude of their achievement in stopping Westway. We cycling advocates can identify, having blocked Mayor Ed Koch’s 1987 midtown bike ban on a legal technicality after gaining public and political standing through raucous protests. But whereas our “bicycle uprising” was grand fun over a brief season, Carolyn’s and Brian’s anti-Westway campaign consumed a decade and played out in numbing legal proceedings and stultifying studies.

Their reward for stopping Westway and helping spark New York City's transit revitalization? Exile of their joint consulting company from city and state work, much of it facilitating public participation in transportation planning, that had become their bread and butter. From the late-1970s on, Carolyn and Brian remained largely blocked from professional advancement and barred from the halls of power.

Carolyn’s and Brian’s legacy endures, however, though it is so pervasive that it’s easily taken for granted. It lives in the clean air revolution that arguably slashed pollution levels sooner and deeper in New York than in any other U.S. city. In Transportation Alternatives, of which Brian was one of five founders in 1973, and which carries forward Citizens for Clean Air’s iconoclasm against the automobile. And, soon, in congestion pricing, for which Brian and Carolyn campaigned ceaselessly from the early '70s into the new century.

For me, losing Carolyn is also personal. She encouraged my and Brian’s early-1990s explorations of the societal costs of driving that became my career bridge from nuclear power economics to congestion pricing. She tutored me in communication and journalism. She respected my enthusiasms and helped me channel them into effective advocacy. Through force of everyday example, she nurtured my appreciation of New York’s sidewalk life and human ecology.

Carolyn’s and Brian’s marriage helped me pattern my own union with a charismatic and mission-driven partner. Her (step)mothering helped Brian’s son Christopher, now my close friend, mature into a brilliant journalist and author. She managed, somehow, to endure the heartbreak of losing her elder son Eric in a kayaking accident in Utah, in 1991. (Carolyn’s younger son Alex is a real estate entrepreneur in Massachusetts.)

The final words here are Brian’s:

Carolyn spent much of her life helping other people. Her actions affected millions, doing what others would not or could not do, at great sacrifice to herself and her family. I have known Carolyn since 1969. We lived and worked together since 1979. With the help of her stepdaughter Eve, I spent the last decade helping Carolyn get through each demanding day, as she grew weak from Parkinson’s and confused by dementia. It is a sad ending to an adventuresome life well-lived. As 18th Century preacher John Wesley said: "Do all the good that you can."