A car-loving Queens judge issued a scathing indictment of the current wave of lawsuits challenging the city’s right to add bus-only lanes and protected bike lanes saying they are neither arbitrary nor capricious but are, in fact, “progress.”

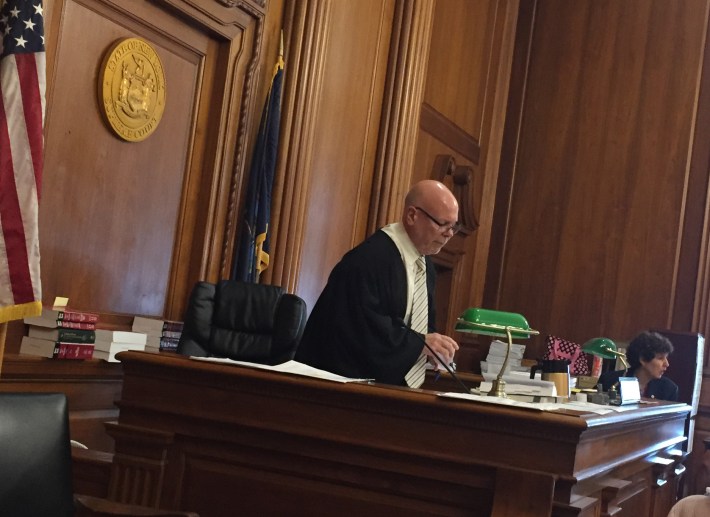

Supreme Court Justice Joseph Esposito was defiant in his position that the city Department of Transportation did not violate state environmental law when it installed a afternoon-only dedicated bus lane on Fresh Pond Road in Ridgewood, where business owners, like other such groups fighting similar city projects in the Bronx and Manhattan, sued on the grounds that the city is acting in an “arbitrary and capricious” manner.

Esposito allowed the plaintiff’s lawyer Arthur Schwartz to make a few substantive points in Monday's brief hearing about the business owners’ belief that the bus lane will hurt their bottom line by removing parking on the commercial strip, but then told Schwartz to sit down.

He'd heard enough.

“You know why they don’t like it [the bus lane]? It’s because nobody likes change,” said Esposito, who had visited Fresh Pond Road in a bizarre fact-finding mission last week.

Esposito then sermonized from the bench with such righteousness (some of it completely erroneous, of course) that Streetsblog will print his comments verbatim:

I’m a car driver. I don’t like change either. I don’t like the changes one bit. The city has put in too many speed bumps. too many red light cameras. Too many speeding cameras. There are too many traffic agents writing tickets and harassing car drivers who just want to go into Dunkin Donuts for a cup of coffee for five minutes. But it’s not about me. It’s not about a narrow group of people who use the roads anymore. You have car drivers, truck drivers, bus riders, pedestrians and cyclists — and everybody has to share the road. You don’t see that, Mr. Schwartz? You have a very parochial, very narrow view.

I’m trying to be honest with you because I don’t see this as arbitrary and capricious. If I was just a car advocate, I would agree because I don’t like driving a car anymore. And maybe Manhattan will someday be car free. But Manhattan is not Queens. which is why I made the visit. People in Manhattan don’t drive cars. They walk. They take the bus. They use Uber. That’s how they live. But we don’t live that way in Queens. You need a car. So as a driver, you deal with it. But it’s not about one group, Mr. Schwartz, whether it’s a business group that you represent, or car owners, or bicycle riders. They’re a dangerous group, too. My wife was knocked down by a cyclist. Everyone is competing for space. Everyone wants to get to work on time. The bus lane will speed up traffic on that street. I’ll be blunt. This is a very narrow rational plan to speed up traffic.

Some people don’t like it and that’s the nature of progress. They used to make buggy whips. Remember buggy whips, Mr. Schwartz? Now they’re out of business. You have to move along. You have to progress with the times. If you don’t see where I’m going with this — what else do you have, Mr. Schwartz?

Schwartz referred to buggy whips, made a quiet joke about not wanting to beat a dead horse and, wisely, sat down. A city lawyer, also reading the room, declined to say a word except that he was available if the judge had any more questions.

Obviously, he did not.

“Being a car driver myself, if it was up to me, I’d grant your petition, Mr. Schwartz, but I cannot,” Esposito said. "It is not arbitrary and capricious. It’s rational. It makes perfect sense. This proceeding is dismissed.”

City lawyers declined to comment, but were clearly delighted. It’s their first outright win in the four cases currently working their way through various courts, including Schwartz’s suit against the 14th Street busway, plus other suits against a road-diet plan for Morris Park Avenue and a protected bike lane on Central Park West.

All of the pending suits share one thing with the Fresh Pond Road suit — they seek to kill various road safety or mobility projects on the grounds that the city did not undertake a full environmental review that is required for major projects under state law. The city says that bike lanes and bus lanes do not meet the threshold of requiring a “hard look” because they amount to merely repainting lines on a roadway.

Schwartz had also argued that the bus lane would hurt Ridgewood businesses because of the removal of parking, but Esposito, who has admitted that he doesn’t go anywhere unless he can park, said that Schwartz did not present any compelling evidence that businesses will necessarily be undermined.

“Removing 70 spots might help the businesses,” Esposito said. “It may not hurt the businesses. You don’t know.”

Esposito’s ruling has no bearing on the other cases, but sends a strong message to anti-city groups that it’s difficult to meet the high threshold of proving that city efforts to speed buses or protect cyclists amounts to an unreasonable reconfiguration of public space or is being done in an arbitrary fashion.

“They’re supposed to be experts,” Esposito said of the DOT. “That’s why they hire all these smart people. I’m not an expert. Neither are you, Mr. Schwartz.”

Outside of court, Schwartz, decked out in an orange-and-blue color scheme befitting his beloved New York Mets, admitted that filing a lawsuit under state environmental law “was always a tough argument” and said his client would consider an appeal.

"I do believe that government is supposed to look at things, not just say, ‘Whatever we say is gold,’” Schwartz told Streetsblog. "I believe that government should be transparent and that communities should have a big say in how you do things. But, yes, the government has a lot of discretion [to act], which is why there are not more lawsuits like this."