New Amsterdam, meet actual Amsterdam.

Crowded streets in Lower Manhattan must give more space to throngs of tourists and other pedestrians with new designs that would bring motorists to a crawl, says a neighborhood group that is pushing the European-styled solution against a mayor who has refused to implement changes to reduce the vast domain of the automobile.

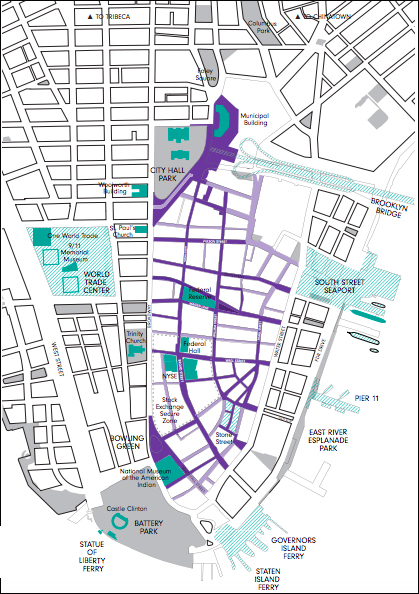

The Financial District Neighborhood Association is seeking the obvious mix of more small parks, fewer parking spaces set aside for city workers and overnight sanitation collection — but the exciting "Make Way for Lower Manhattan" plan [PDF] also calls for the elimination of several roadways to create an expanded Bowling Green and a plaza at the crowded end of the Brooklyn Bridge.

The proposal takes inspiration from shared streets programs across the world, such as La Rambla in Barcelona, most of Amsterdam and Istanbul's Golden Horn.

“Our thinking is something like a slow streets program, something that has been done in cities across the world,” said Patrick Kennell, the group's founder.

New Yorkers have been wondering how to solve congestion below Chambers Street since, well, before there was a Chambers Street. The street grid — such as it is — dates back to the original Dutch colony of New Amsterdam. All those small lots encouraged skyscraper construction, which was great for Lower Manhattan's dominance as a world capital, but was not so great for movement of goods and people.

One hundred years ago, the key to easing congestion was to build a subway system that sped development northward. But the rise of the automobile complicated that effort. And when sidewalks and roadways feel so narrow, no one wants to give up any space.

And the re-emergence of Lower Manhattan as a residential area in the mid-1960s created new challenges. In 1966, then-Mayor Robert Wagner convened a panel of the best and brightest urban planners, who created a 368-page “Lower Manhattan Plan,” which proposed a mix of streets: some for fast-moving traffic, some for delivery vehicles only, and others set aside for pedestrians only. (After the 9/11 terror attacks, some of the area around Federal Hall and the New York Stock Exchange became pedestrianized, but mostly as a security measure — though the areas are popular with tourists, too.)

In 2010, as the downtown population surged towards its current 75,000, the Department of Transportation recommended transformation of many Lower Manhattan streets into "shared" roadways. Very few were actually implemented.

But congestion in Lower Manhattan has reached a crisis, thanks to more cars (and more illegal parking), more vendors, more tourists, more pedestrians, more cyclists and more garbage, the group says. (On some streets, half the parked cars are flashing government-issued, sometimes counterfeit, placards.)

"These issues threaten to undermine both the quality of life in New York’s most historic district and its ability to grow," the report said.

The solution, of course, is to reduce the space for automobiles — and completely pedestrianize part of Lower Broadway and Centre Street from Chambers to below City Hall.

"A reimagined Brooklyn Bridge-City Hall Plaza, focused around a new fountain or monument, could become one of NYC's signature public spaces by ensuring that cars coming off the Brooklyn Bridge are not able to enter the city street grid at Chambers Street," the report said. "Instead they would enter Lower Manhattan from streets north and south of the Bridge off of the FDR Drive."

And the widened pedestrianized area near the Charging Bull sculpture would allow tourists to interact with the statue and make better use of the currently under-visited Bowling Green, the report added. It's no coincidence that these two major walking areas connect through the largely pedestrianized area near the stock exchange.

"[These] three major gathering places that celebrate FiDi’s history could anchor the slow-street district," the report said, citing the desire of tourists to move seamlessly among attractions, just as visitors in London, say, move from the National Gallery to Nelson's Column in Trafalgar Square without having to encounter cars. And more shared streets — where cars and pedestrians mingle at walking speed — mimic the approach of cities like Amsterdam.

"Interventions in Amsterdam, for example, have proven that the best way to slow drivers is to remove most of the tools that traffic engineers developed in the 20th century to make drivers feel comfortable driving quickly," the report said. "The Dutch slow streets, comprising roughly 85 percent of the streets in central Amsterdam, almost counterintuitively have no traffic lights, traffic signs, crosswalks, or painted road arrows. A pedestrian or cyclist may be anywhere in the street at any time. Many of these slow streets have no sidewalks, and none of them have bike lanes (those are reserved for faster streets)."

As such, the report does not create any truly large car-free zones, as its authors likely realized that such a proposal — though implemented successfully many world-class cities — is a non-starter for Mayor de Blasio, who has consistently rejected the idea. But this mayor will be gone in two years. One of his would-be successors, Council Speaker Corey Johnson, says he would be far more aggressive in "breaking the car culture" than de Blasio has proven in his second term.

But the mayor's Department of Transportation is open to some of the Lower Manhattan proposal.

"We’ve held a Shared Streets event in the area previously and we welcome input such as this, which we will review," said agency spokeswoman Alana Morales.

Transportation advocates say the Lower Manhattan proposal is a step in the right direction for reclaiming streets for pedestrians.

“This is going to start a lot of conversations about the role of the automobile in New York City, and that’s a conversation we should’ve been having a generation ago,” said Joe Cutrufo of Transportation Alternatives. “It’s a pedestrian rich, transit rich area, why are we dedicating so much space to cars?”

And in case anyone is worried about the Amsterdamification of New Amsterdam, the former bike mayor of the idyllic Dutch pedestrian and cycling haven says residents of her city quickly figured out how to share the space. And few people chose to drive into many areas of the city because it costs too much to park.

“You just need time to educate people that are walking and cycling that they need to pay attention,”Anna Luten told Streetsblog. “And car drivers [will become] aware that they are guests.”