Robert Moses built the Prospect Expressway for a few million dollars in the 1950s, cutting a scar between Park Slope and Windsor Terrace. Now, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams is championing a plan to spend upwards of $100 million that to heal the wound.

On Monday, Adams released "PX Forward," a report [PDF] commissioned from NYU's Wagner School of Public Service that called for transforming the mostly below-grade highway from a blighted trench to create space for new parks, new development and better transportation infrastructure.

"Windsor Terrace and Park Slope were ripped apart by this trench," Adams said. "We must reunite these neighborhoods physically and emotionally. This is a canyon through two communities...not a canyon made by nature, but by Robert Moses."

The 69-page report, written by NYU-Wagner graduate students, offers 11 recommendations. Some are quick fixes, such as altering light timings, re-routing trucks or adding a four-way stop at Seeley Place and 19th Street, while other mid-priced changes include closing some entrance ramps and opening new ones.

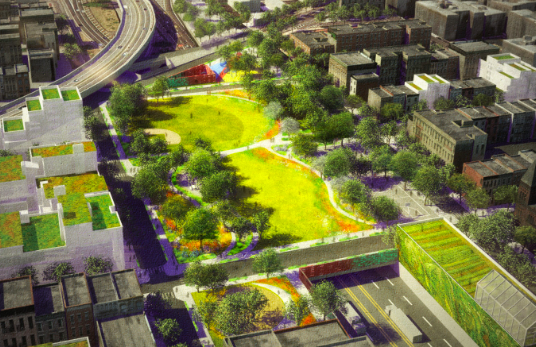

But the big-ticket items include megaprojects such as decking the entire expressway or filling the trench to create an at-grade boulevard modeled on the Embarcadero in San Francisco or the West Side Highway below 57th Street in Manhattan.

Both of those last proposals would cost tens of millions. So as a fallback, the NYU-Wagner planners offered something dubbed, the Prospect Path, "a cantilevered linear park running along the below-grade length of the expressway."

"[It would] both extend the sidewalk and improve user experience by creating height and distance from vehicular traffic," the report says. "The Prospect Path could also incorporate elements such as dedicated walkways for pedestrians, bike lanes for cyclists, passive seating, and planters."

Another proposal calls for using some of the currently inaccessible shoulder space on the highway for public buildings such as libraries that can be accessed from the raised sidewalk.

But by far, the two most radical proposals — decking the roadway or turning it into a wide boulevard — are the eye-catchers. Let's unpack them:

Decking the halls

Covering over the two-mile below-grade portion of the highway would cost hundreds of millions of dollars, if other cities' experience, and other proposals in New York, serve as a guide. New Jersey spent $150 million on a short deck over Route 29 to create "Riverwalk," a park linking the city to the Delaware River. But the presence of the park led to a surge in local real estate values that partially offset the cost.

Dallas spent $60 million to build a park over a three-block stretch of the open-trench Woodall-Rodgers Freeway, connecting the city’s downtown and arts district to its Uptown neighborhood. Condo towers are proposed for each side, with one developer gushing to the Dallas Tribune that the park “will be a fabulous amenity to [my] building.”

Indeed, the only way to make decking work is apparently to have private developers involved from the state.

"As in other cities, innovative partnerships between federal and local governments and private parties may present a unique funding opportunity," admitted the PX Forward planners, echoing several prior studies.

In 2008, for example, a city study on fixing trench highways deadpanned, "Decking over a transportation corridor can be very expensive."

"The cost of decking could mean that either public subsidies or high densities would be needed in order to make such a project economically feasible," the report continued. "As a result, privately built buildings constructed over transportation rights-of-way are often large and tall in order to minimize the cost of footings and decking and to provide sufficient revenue to justify the level of investment required.

"Such proposals," the report concluded, hinting at neighborhood concerns about skyscrapers, "need to be evaluated in the context of the communities in which they would be built."

More recently, a 2016 proposal to deck over and beautify an even shorter below-grade portion of Brooklyn-Queens Expressway through Williamsburg was priced at $100 million. That proposal, called "BQGreen," is still on a drawing board.

Decking is so daunting that a 2010 study of the below-grade portion of the BQE between Atlantic Avenue and Summit Street through Carroll Gardens did not even address the possibility.

Instead, the proposal offered piecemeal treatments such as planting more street trees, installing acoustic barriers, adding pedestrian bridges or even building a "Green Canopy" of vines and solar cells over the exposed highway.

As a result, the proposals ranged from $10 million to $50 million.

A new Brooklyn Boulevard?

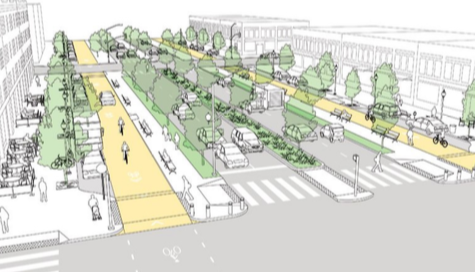

The report's other high-cost option calls for filling in the trench and raising the roadway to street level — then "reducing the number of vehicle traffic lanes and introducing new paths for cyclists and pedestrians."

"Adding medians, traffic signals, dedicated bus lanes and pedestrian crossings would create a safe and attractive space for multiple modes of transportation," the report added, citing examples such as Rochester and San Francisco's torn-down Embarcadero Freeway, now a grand boulevard along the bay.

"Boulevarding would enhance mobility for pedestrians and cyclists by providing more points of connectivity across and along the Expressway," the report says. "Converting the Expressway into a multi-modal thoroughfare would also calm traffic, thereby enhancing safety. The addition of pedestrian green space would promote opportunities for recreation."

The Regional Plan Association pushed such a proposal in 2017 over costlier decking schemes that the group preferred for several other open trench highways in the city. The RPA boulevard proposal was more radical than the current student white paper, saying the expressway should "be narrowed to one lane in each direction, opening up land for a new bicycle 'highway,' residential development, and public spaces."

PX Forward's boulevard plan hints that the expressway would retain at least two lanes for cars.

On Monday's unveiling of the study, Adams declined to say what plan he would push for, or how he would get state and local authorities to commit funding.

"This study is a call to action," he said.