When New York City Transit says it's embarking on a "top-to-bottom" overhaul of "the entire city’s bus route network," that's music to Jarrett Walker's ears.

Walker is the consultant who specializes in guiding transit agencies through the process of redesigning their bus networks -- most famously in Houston, and most recently in Dublin. At a time when transit ridership is slumping nationally, Houston is one of the notable exceptions. Its redesigned bus network, which brought frequent service to new parts of the city, deserves substantial credit.

With the MTA embarking on a total overhaul of the bus network in all five boroughs by 2021 (the Staten Island express bus network was the warm-up), Walker's fundamental advice is to start by "wiping the slate clean," he told a crowd at TransitCenter last week. Only a blank canvas will yield "design choices based on the whole network," he said, which in turn produce benefits compelling enough to "overcome little problems."

For transit planners who know their bus network and each justification for all of its quirks inside out, it can be difficult to let go and think freely. At the bus network redesign workshops he leads for transit agencies and city DOTs, Walker insists that participants refrain from discussing historical reasons for routes and steer clear of anticipating political objections (as in, "that parking space over there belongs to a business owned by the city councilor's cousin").

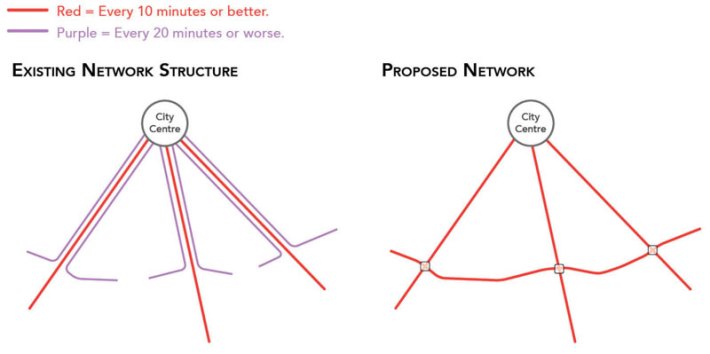

In Dublin, that meant completely redoing a system that emphasized one-seat rides at the expense of frequency. With the old network, riders could avoid transfers, but they sacrificed in the form of longer waits. Under the new bus network design, unveiled earlier this week, service will be simplified into core routes that arrive much more frequently, which is projected to reduce total wait time even though riders will have to make more transfers.

The politics of these major redesigns are never easy. ("Beautiful people will come to you with their elderly parents and their babies and say the redesign will ruin their lives.") But with a sweeping overhaul, the benefits should be substantial enough to win over elected officials and other community leaders.

As Walker put it, "It's easier to take out half of all bus stops than each stop one by one." (Strategic advice that's especially relevant for New York, where stops spaced too close together drag down bus speeds and stop consolidation will have to be embedded in any effective bus network redesign.)

Walker describes his role in the redesign process as a facilitator, and he didn't want to go into prescriptive detail about how to improve New York's bus network.

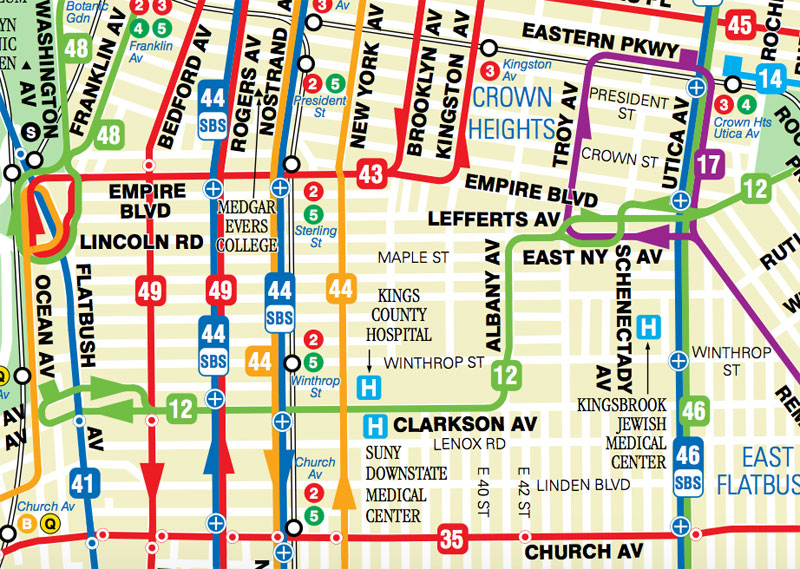

But he did point out the inconsistent distances between parallel routes in Brooklyn. Where parallel routes are close together, riders don't have to walk far to get to a stop, but they have to wait longer than they would if service was concentrated on fewer streets.

Walker also stressed the importance of a bus network that transcends the boundaries between boroughs. While the waterways dividing the land masses of New York justify separate bus networks to some degree, he also sees artificial distinctions in the current network.

When you wipe the slate clean, he said, "There's a way to look at Brooklyn and Queens as one thing."