Amsterdam Avenue in Upper Manhattan is the kind of four-lane traffic free-for-all that costs lives. Between 2010 and 2014, drivers killed four people on Amsterdam above 110th Street. But instead of endorsing basic safety measures that have proven to work on other NYC streets, Manhattan Community Board 9 keeps resisting any changes to the configuration of car lanes.

It's been nine months since DOT first presented a safety overhaul of Amsterdam Avenue north of 110th Street. Last night, the agency showed a watered down version of that plan to the CB 9 transportation committee, but chair Carolyn Thompson wasn't appeased, insisting on at least a few more months of delay before voting on the project.

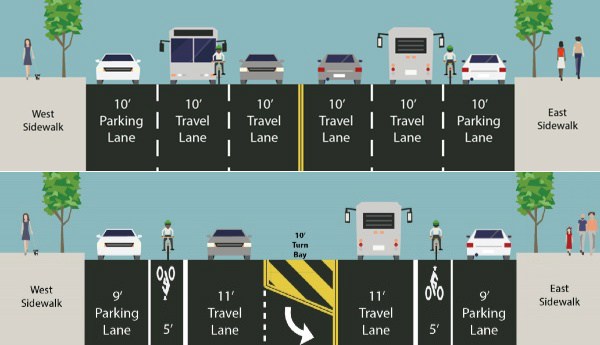

The original plan called for a standard road diet on Amsterdam between 113th Street and 162nd Street, reducing the number of motor vehicle lanes from four to two, with left-turn pockets. It also included unprotected bike lanes in both directions, and concrete pedestrian islands at about a dozen intersections. But after some members of CB 9 balked after a presentation in the spring, DOT scaled back the plan.

The new version maintains two lanes of northbound motor vehicle traffic between 135th Street and 145th Street (the bike lane is still in that section, but not a painted median) [PDF]. In a better modification, DOT also added commercial loading zones to reduce double-parking. The iteration presented last night was an attempt to compromise, said DOT project manager Brian Hamlin.

Thompson didn't see it that way. "You're still removing a lane. And that's what we don't want," she told Hamlin.

But to say the project "removes a lane" ignores how road diets work. Four lane, two-way streets are inefficient as well as dangerous, with a lot of unnecessary merging, because left-turning drivers stop traffic behind them while waiting for gaps in oncoming vehicles. The redesign DOT presented imposes order on traffic flow -- drivers making left turns, motor vehicle through traffic, and people on bikes all have designated space.

The result is a reduction in crashes without much change in car capacity. Streets all over New York City have received similar treatments in recent years.

Nevertheless, most of the discussion consisted of Thompson repeatedly hammering her concerns about traffic and the loss of car lanes, while Hamlin and DOT Bicycle Program Director Ted Wright reiterated that the modified design was an attempt to compromise. DOT's traffic analysis showed no impact on travel speeds as a result of the redesign.

"We heard you, and that's really what you're seeing today, is us pulling back -- we understand your concerns," Wright said.

Another CB 9 veteran, Ted Kovaleff, objected to the very idea of "cutting out a lane to be able to put in a bike lane." The scene was almost a repeat of the 2015 discussion of the Riverside Drive road diet, which Thompson and Kovaleff also fought.

Community board members serve two-year terms with no legal limit on consecutive terms. It's up to council members and borough presidents to change the personnel who sit on community boards, through their power to make appointments. Thompson and Kovaleff were both appointed to CB 9 most recently by Borough President Gale Brewer.

Last night, Thompson eventually conceded that the plan was "better" in her mind, and other committee members expressed support for it, but she still insisted on tabling it until the next committee meeting in February. Despite nine months to consider the project, Thompson and some of her colleagues said they needed more time to read through the plan. "The thing about it is, we want to read the proposal," Thompson said. "Then we can meet in February."

The small room was packed with over a dozen supporters of the project.

"I’ve probably been to this board five times over the course of the year to discuss this bike lane,” said Adam Sacarny, who lives in the neighborhood but doesn't bike on Amsterdam because it feels dangerous. “I thought it was telling that all of the community board’s questions were about the effects of this policy on car traffic, and the experience of car drivers, and people who are in cars, and not all of the residents who are biking and walking and using the street, who vastly outnumber the people in cars.”