More than one-quarter of the pedestrians and bicycle riders whom drivers killed in the five boroughs last year would still be alive if the kinds of street safety treatments already in place at 15 percent of New York City intersections had been installed universally, according to Manhattan Institute fellow Alex Armlovich, whose new report assessed the effectiveness of NYC DOT safety-related street redesigns.

The report, "Vision Zero and Traffic Safety," confirmed that street design interventions made under the rubric of the city’s Vision Zero initiative are measurably reducing pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities in communities in all five boroughs. It also found that lower-income neighborhoods are receiving fewer street treatments despite their higher rates of crash risk, a deficit the report attributes in part to community board resistance and apparent indifference to the resulting higher fatality rates.

Transportation Alternatives and other street-safety advocates have for years urged street treatments such as shortened pedestrian crossing distances, leading pedestrian intervals (LPIs), bike lanes, and speed cams. The report quantifies their value with new statistical tools that allow us to estimate the injuries and fatalities that could be averted by installing these treatments more widely and rapidly.

For one quantification, Armlovich developed a “Vision Zero Improvement Index” (VZII) -- an original metric based on DOT Vision Zero data feeds summarizing the number of LPIs, traffic signal re-timings and other treatments installed in the last three years in each of NYC’s 59 community districts, excepting the four districts that make up the Manhattan CBD and one covering downtown Brooklyn (for which the influx of workers, shoppers and daytrippers might skew the results). His assigned VZIIs ranged from barely above zero for SI3 (Tottenville, Woodrow, Great Kills) and Q14 (the Rockaways and Broad Channel) to a maximum of around 3.5 for BK8 (Crown Heights North). Armlovich then correlated these metrics to the change in each district’s pedestrian injuries and fatalities in 2016 versus a 2009-2013 baseline.

The result (tucked away in a graph in the report) is a statistical association of a one-unit gain in each district’s VZII to a 7.5 percent drop in that district’s pedestrian casualties in 2016 versus the five-year baseline. If we extrapolate from that relationship and postulate an aggressive citywide redesign to raise the average VZII from its actual value of around one at the start of 2016 to, say, five, we could conclude that pedestrian casualties last year would have been 30 percent less than in the baseline period. (I calculated that by multiplying the postulated change in VZII of four times 7.5 percent.) The actual drop was far less, only around 10 percent, pointing to enormous missed opportunities to make walking safer.

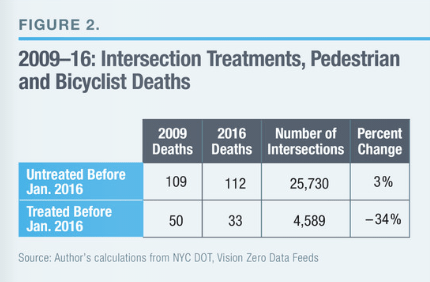

That quantification is dominated by pedestrian injuries, which far outweigh fatalities. Asked to examine the latter, Armlovich made a simple but devastating calculation, based on the divergence in pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities between the nearly 4,600 NYC intersections that received some safety improvements prior to 2016 and the 25,700 that received none. At or near treated intersections, fatalities fell by a whopping 34 percent; whereas at or near the untreated ones, they rose slightly (see table).

(Incidentally, a chi-square test indicates that the divergence in fatalities between the two classes of intersections is significant to the 1.5 percent level, indicating that the difference in outcomes isn’t merely the result of random chance. The upshot, then, is that the Vision Zero design interventions actually do lower the rate at which drivers kill pedestrians and cyclists.)

Pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities totaled 159 in 2009 and 145 in 2016. What if all city intersections, not just 15 percent, had been redesigned for safety prior to 2016? Because fatalities at treated intersections were only 66 percent (that’s 100 percent less 34 percent) as great in 2016 as in 2009, Armlovich theorizes that deaths last year would have been just 66 percent of the 2009 total of 159, or 105. That’s 40 fewer deaths than the actual 145. The absence of safety treatments at those 25,700 intersections thus translates to 40 deaths last year that could have been prevented, but weren’t.

Why aren’t street safety improvements being made faster? Actually, some 5,000 new treatments were added in 2016, a record almost equaling the combined 5,600 in 2014 and 2015, which themselves were record rates at the time, according to a graphic in the report. Armlovich also notes that DOT is targeting “priority [high-casualty] intersections” as a way to “get the bad intersections first and work their way out from there” -- a smart strategy, to be sure.

All too often, however, local elected officials and their community board allies block the way, especially in less-affluent parts of the city, according to Armlovich:

Lower-income residential neighborhoods have not received intensive Vision Zero treatment relative to their risk, and continue to suffer higher pedestrian-crash rates [even though] DOT’s Vision Zero plans appropriately target lower-income neighborhoods in proportion to risk… In addition to opposition from elected officials, community boards … have resisted change, as well.

The tragic irony is that despite the successes of Vision Zero to date, “lower-income neighborhoods were and remain more dangerous than middle-income and higher-income areas,” Armlovich writes, not because of insufficient attention from DOT but because of entrenched opposition. He concludes:

[T]o continue reducing risks to pedestrians and bicyclists posed by poorly governed motor-vehicle traffic, the city must continue to overcome neighborhood opposition to traffic safety improvements.

Thanks to Armlovich and the Manhattan Institute, DOT and safer-streets advocates will have new, potent tools to do precisely that. As the killing of cyclist Dan Hanegby by a charter bus driver in Chelsea earlier this week indicates, the need for citywide street makeovers is as great as ever.