This week, U.S. DOT released guidelines for self-driving cars, a significant step as regulators prepare for companies to bring this new technology to market. Autonomous vehicles raise all sorts of questions about urban transportation systems. It's up to advocates to ensure that the technology helps accomplish broader goals like safer streets and more efficient use of urban space, instead of letting private companies dictate the terms.

The rules that the feds put out will be revised over time, and the public can weigh in during that process. With that in mind, I've been reviewing the guidelines and talking to experts about the implications for city streets -- and especially for pedestrian and cyclist safety. Here are a few key things to consider as regulations for self-driving cars get fleshed out.

Fully autonomous cars can't break traffic laws.

The feds say self-driving cars should adhere to all traffic laws. In practice, this means they'll have to do things like obey the speed limit and yield to pedestrians in crosswalks. Following the rules may be a pretty low bar to clear, but it's more than most human drivers can say for themselves.

Transit advocate Ben Ross points out, however, that this standard will only apply to "highly automated vehicles" (HAVs). Cars that are lower down on the autonomy spectrum -- where a person is deemed the driver, not a machine -- wouldn't need to have features that override human error.

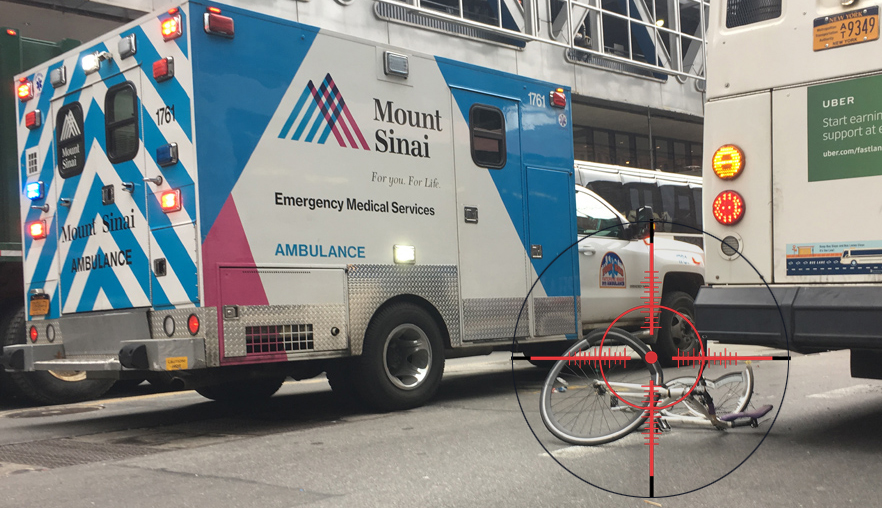

The guidelines mention pedestrians and cyclists, but don't get very specific.

Among U.S. DOT's core requirements for self-driving cars are that they will have to:

- Yield to Pedestrians and Bicyclists at Intersections and Crosswalks; and

- Provide Safe Distance From Vehicles, Pedestrians, Bicyclists on Side of the Road

Beyond that, the guidelines don't say much.

Robert Schneider, a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee planning professor who specializes in pedestrian issues, flagged this passage as cause for concern (apologies for the alphabet soup):

Entities should have a documented process for assessment, testing, and validation of their OEDR [Object and Event Detection and Response] capabilities. Within its ODD [Operational Design Domain], an HAV’s OEDR functions are expected to be able to detect and respond to other vehicles (in and out of its travel path), pedestrians, cyclists, animals, and objects that could affect safe operation of the HAV.

Scheiderman said this phrasing makes pedestrians and cyclists subsidiary to the vehicle and its occupants.

"I think that places emphasis on the wrong roadway user," he said. "Pedestrians are more vulnerable then vehicle occupants when a collision occurs, so automated vehicles should be designed to detect pedestrians first and foremost to prevent injuring pedestrians and then to ensure safe vehicle operation."

It may be that technology governing how automated vehicles interact with pedestrians is simply too undeveloped to include in this early round of guidance. U.S. DOT has said that some guidelines are intentionally vague or flexible to allow room for innovation.

"We need a lot more documentation and research from the pedestrian side to know what is the impact of vehicles in these initial pilot tests to see how they are interacting with pedestrians,"said Schneider.

Regulators don't make much distinction between driving in a city environment full of people and driving on a highway.

Although fully-automated vehicles are being tested in Pittsburgh and Silicon Valley right now, and automakers expect them to be on the market in two to four years, the guidelines don't emphasize the distinction between how vehicles should operate in urban, rural, and suburban environments. The word "cities" appears just once in the 116-page document and the word "urban" appears twice.

In a statement, the National Association of City Transportation Officials urged "that final guidance and rule-making be based heavily on urban streets, where people walking, parking, biking, and making deliveries create a complex environment for driving."

In another worrying sign, U.S. DOT recommends that statewide policies on autonomous vehicles be controlled by a board that includes the state DOT, toll authorities, and transit agencies, but not local government officials. Unless that is changed in the final guidance, board without city representation lead to decisions that overlook the needs of urban residents. Policies about 21st Century transportation systems shouldn't repeat the mistakes of the 20th Century and exclude city residents from the picture.

Not much emphasis on vehicle speed.

Safety is the overriding theme of the document. So it's surprising that vehicle speed is not discussed, given the extent to which managing speeds can prevent serious injuries and fatalities, especially in urban environments. If you search the document for the word "speed," in fact, most references are about speeding up the regulation process or the process of bringing automated vehicles to market.

Schneider singled out this passage discussing the ethical calculations automated cars will have to make:

Similarly, a conflict within the safety objective can be created when addressing the safety of one car’s occupants versus the safety of another car’s occupants. In such situations, it may be that the safety of one person may be protected only at the cost of the safety of another person. In such a dilemma situation, the programming of the HAV will have a significant influence over the outcome for each individual involved. Since these decisions potentially impact not only the automated vehicle and its occupants but also surrounding road users, the resolution to these conflicts should be broadly acceptable. Thus, it is important to consider whether HAVs are required to apply particular decision rules in instances of conflicts between safety, mobility, and legality objectives. Algorithms for resolving these conflict situations should be developed transparently using input from Federal and State regulators, drivers, passengers and vulnerable road users, and taking into account the consequences of an HAV’s actions on others.

Schneider points out that at lower speeds, the need for ethical calculations like this would be reduced, because the risks would inherently be smaller.