Talk about running in place: At current growth rates in subway ridership, the service increases that NYC Transit is promising to roll out next June will probably be used up by April.

That doesn’t mean the increases are a bad idea, of course. Rather, it underscores the need for transformational increases in subway capacity, rather than incremental moves like the bump announced by the MTA last Friday.

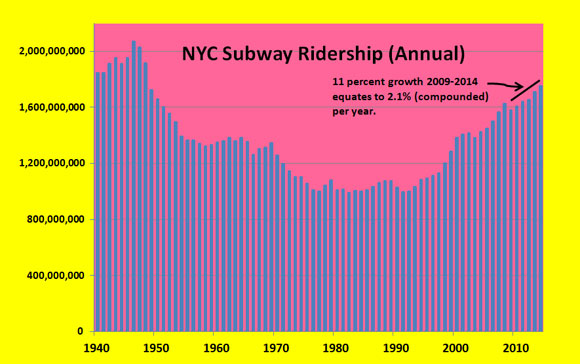

Here’s the deal: Annual subway ridership increased every year from 2009 to 2014. (Data for 2015 aren’t in yet.) The 11 percent rise, to 1.75 billion trips last year from 1.58 billion in 2009, works out to an annual average increase of 2.1 percent. There are now 6 million subway trips on a good weekday, with some 90 percent of those trips, or 5.4 million, happening between 6 a.m. and 7 p.m. Just a single year’s growth, at 2.1 percent, amounts to 113,000 rides during that 15-hour peak.

By comparison, the 36 additional trains that NYC Transit intends to run on weekdays -- 10 on the 1/2 line, six on the A/C/E, six on the J/M/Z, and 14 on the 4/5/6 -- will add room for 45,900 additional passengers (multiplying 36 trains by 10 cars per train by 127.5 riders per car). Throw in 5,000 to 10,000 more spaces for the greater frequency promised on the 42nd Street Shuttle, and the total gain in capacity reaches 55,000 -- enough to handle a mere six months' worth of ridership growth.

The takeaway is that enhanced service commitments like last Friday’s will be needed much more frequently. The only way that will happen is through transformational change, like implementing Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC) on every line.

CBTC supplants the century-old analog "fixed block wayside signal" system for monitoring and controlling train movements. In its place will be fiber-optic communications that link tracks and vehicles into a seamless system, as the Regional Plan Association summed it up in its comprehensive report on CBTC earlier this year. In a nutshell, where subways currently run at 20-25 trains per hour, CBTC would allow at least 30.

If that could be done across the system, a simple calculation -- 14 lines (I exclude the L, which was already upgraded to CBTC) times 7.5 more trains per hour times 15 hours per day times 1,275 additional passenger capacity per train -- suggests an increased capacity of 2 million passengers per day. That means subways could carry at least one-third more passengers than the estimated 5.4 million riders now traveling between 6 a.m. and 7 p.m., when the trains are most crowded. Or some of the new capacity could alleviate crowding, not only making subway travel more humane but reducing delays caused by crowding itself as passengers struggle to enter and exit packed trains and stations.

The calculation here doesn’t address logistical concerns, not to mention costs of buying, staffing, servicing and running the increased trains. But it underscores the vast potential and need to begin bringing subway infrastructure into the 21st Century now -- a process that will require full funding of not just the current MTA capital plan but future five-year plans as well.