Governor Cuomo's post-Sandy infrastructure commission unveiled its recommendations [PDF] last week, and while it focused heavily on hardening the city's transportation network against future storms, it also offered glimpses of how infrastructure could be more resilient in the wake of disaster, with Bus Rapid Transit playing a prominent role.

In addition to BRT, the report from the NYS 2100 commission supported rail capacity expansions, including the Gateway Project across the Hudson River, Metro-North service to Penn Station with additional stops in the Bronx, communication-based train control on the subway, and adding tracks to the LIRR's Main Line.

But there's a big difference between a report and implementation. Albany will have to take steps to make most of the commission's recommendations a reality, and early indications that Governor Cuomo will prioritize transit improvements aren't promising.

The recommendation for comprehensive BRT isn't just about disaster preparedness. It offers an opportunity to reach populations underserved by existing rail networks in outer-borough and suburban job centers while also providing flexible transit that can pick up some of the slack in the event of a subway shutdown.

The post-Sandy "bus bridge" between Brooklyn and Manhattan showed the value of BRT, the report states, and the success of Select Bus Service -- bus improvements that have cut travel times and attracted new riders -- demonstrates the opportunity to expand, both by incorporating more BRT features in SBS projects and by creating new busways throughout the city.

"The SBS system we have now has helped to introduce a new thing to New York," said Gene Russianoff of the Straphangers Campaign. "But at this rate, it will be a long while before we have a world-class BRT system."

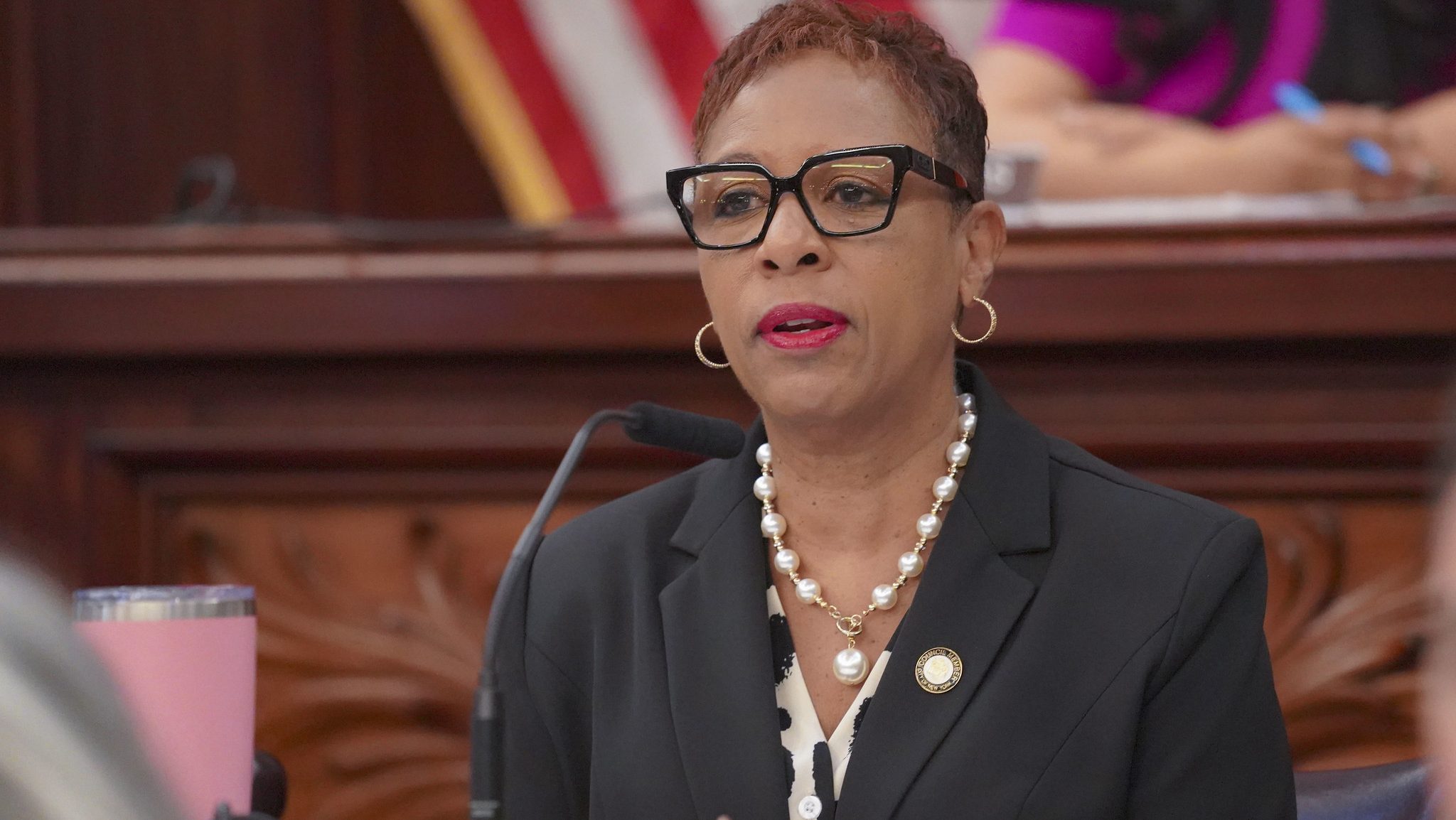

The NYS 2100 report recommends a study commission to evaluate routes for a BRT network, a suggestion Russianoff embraced. But Veronica Vanterpool, executive director of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign, questioned the need for another task force after years of planning for SBS and BRT systems.

Noting that BRT would be a cost-effective means to essentially expand the existing transit network, Vanterpool said it remains to be seen how the NYS 2100 recommendations will move forward. Ultimately, the projects that would build out a robust BRT network should be included in the next MTA capital program, which will invest in system expansion and maintenance from 2015 to 2019. "Really, funding is the impediment," Vanterpool said.

The specifics of the next capital program have not yet been developed, and it remains unfunded. Which leads to one of the gaps in the NYS 2100 report: Besides a section advocating for a vaguely-defined infrastructure bank, it doesn't mention how to pay for its recommendations. Debt financing alone, whether backed by fares or the state's tax revenues, won't cut it. (Last week, State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli raised a red flag concerning the state's growing reliance on debt. The state's debt burden has increased 62.2 percent in the past decade, according to the comptroller, growing faster than state spending on Medicaid or education. All but a sliver of this borrowing is by public authorities like the MTA.)

To anticipate future disasters and build back better, as the NYS 2100 commission recommended, the state will have to find a way to fund these improvements. A good place to start: Reform the city's toll system so it stops contributing to traffic dysfunction.