Phineas Baxandall is a senior analyst at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group.

It’s now common knowledge that annual changes in the volume of driving no longer follow the old patterns.

For 60 years, the amount of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) rose steadily. Predicting more driving miles next year was like predicting that the sun would rise or that computer chips would be faster. The only direction seemed to be up.

Then, after 2004, per-capita VMT fell 6 percent, which has led to a decline in total VMT since 2007.

The most recent data are from July, traditionally America’s biggest month for driving. In July 2012, Americans clocked over 258 billion miles behind the wheel, a billion fewer miles than the previous July despite a slightly stronger economy and cheaper gasoline. In fact, you’d need to go back to 2002 to find a July when Americans drove fewer miles than July 2012.

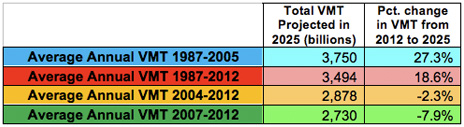

Has America’s long increase in driving turned a corner or just taken a prolonged pause? The answer matters a lot. Consider four scenarios:

- If the volume of annual vehicle miles traveled switches back to the average rate of increase between 1987 and 2005, then by 2025 VMT will be 27 percent greater than the 2012 level.

- If VMT changes at the average rate it sustained over the entire period between 1987 to 2012, then it will grow by almost 19 percent by 2025.

- If instead VMT changes at the average rate that has prevailed since 2004, then the number of miles driven will fall 2.3 percent by 2025.

- And if VMT changes at the average rate that has prevailed since 2007, then VMT would fall off by almost 8 percent by 2025.

The difference spanning these scenarios amounts to over a trillion vehicle miles per year. How we decide to invest in transportation should be very different, depending on which scenario we are planning for – especially since the roads, railways and other infrastructure we build today will be with us long past 2025. Continuing to build new highways at the current pace might arguably make some sense if driving were to return to pre-2005 rates of growth. But those outlays indisputably would be a colossal waste if more recent trends prevail.

There are good reasons to believe the current slowdown in driving may persist. A report by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group earlier this year showed that youth are leading the trend toward less driving. Americans aged 16 to 34 reduced their miles driven by 23 percent between 2001 and 2009. Changing patterns in the use of information technology may be a major factor in reduced driving that is also encouraging growing transit ridership.

It won’t be surprising if an upturn in the economy leads to some increase in driving, especially if gas prices don’t also surge. But it’s harder to imagine that we will switch back to the sizeable increases in VMT that took place almost every year for six decades after World War II. Even if driving continues to increase at the rate of population, this would be a long-term slowdown that should correspond to major changes in transportation policy. While we can’t yet see “the new normal,” it’s a good bet that it won’t be the same as the old normal.

You wouldn’t know that from the last transportation bill. Congress needs to stop trying to build out our grandparents’ transportation system.