Editor's note: This post, the first in a five-part series by Streetsblog contributor Charles Komanoff, recounts the activism that saved and rejuvenated bicycling in New York City 25 years ago. Future posts in this weekly series will place the "bike ban uprising" in the historical context of cycling advocacy. Activists are planning a September 28 bike ride and forum to commemorate and celebrate the events of 1987, and Streetsblog readers are invited to participate and contribute.

************************

You can sit at your computer all day long and you’re never going to get anything done in terms of bringing down a government. What happens is when people got up and went into the streets. -- NY Times Cairo correspondent David Kirkpatrick, interviewed on Fresh Air (NPR), July 18, 2012, A Reporter Looks at Where Egypt May Be Headed.

The Revolution of 1987

Twenty-five summers ago, something remarkable unfolded on the streets of New York City: Bicyclists by the hundreds and even thousands took to the avenues in a series of tumultuous demonstrations -- part protest and part celebration -- that galvanized bike activism.

The demonstrators encompassed the entire spectrum of NYC bicycling in the mid-to-late 1980s: daily bike commuters, weekend recreational riders, bike racers, cycling sympathizers, and bicycle messengers (who in those days were a powerful presence in Midtown traffic and who spearheaded the mid-summer actions). These disparate constituencies joined to resist a mayoral edict banning bicycle riding in the heart of Midtown Manhattan: on Fifth, Madison and Park Avenues from 31st to 59th Street.

The Midtown bike ban would operate from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Monday through Friday, clearly targeting the bike messengers whom the tabloid press and other opinion-mongers held responsible for the city’s rampant traffic chaos and danger, but infringing on everyone’s right to ride and declaring open season on the city’s hardy but beleaguered bicycle community. Flanked by his police and transportation commissioners, Mayor Ed Koch stood on the steps of City Hall on July 22, 1987, to unveil the ban, which would take effect six weeks later, at the start of September, once signs had been posted and the legal niceties disposed of.

The outrage propelling the bicycle demonstrations was predictable enough. Singling out cyclists, a small part of the traffic stream, was ludicrous from a pragmatic standpoint and indefensible from a moral one. Moreover, targeting vulnerable, working-class bike messengers qualified as scapegoating and class warfare. The celebratory aspect was perhaps more surprising, as well as more enduring, for the summer of bicycle protest became an outpouring of frustration, hope and joy: frustration that cycling and cyclists had been maligned for so long; hope that other New Yorkers might stand with us; and the joy that explodes when any marginalized group pours into the streets on its own terms.

We had our terms indeed. Once or twice each week at around 5:30 p.m., the end of the messengers’ workday, masses of cyclists, usually half a thousand and occasionally more, spread across Sixth Avenue and paraded the three miles from Houston Street to Central Park South. Our stately pace, perhaps five mph, was slow enough that passersby could look past our bikes and see our bodies and faces. Walkers and joggers could join our ranks. We were slow enough that we could and did stop at red lights. Letting foot and auto traffic cross at the green was a stroke of genius. It certified cycling as city-friendly and kept the police from using “blocking traffic” as a pretext to bust the permit-less rides. As we streamed up Sixth Avenue, cries of “What do we want? Our streets back!” reverberated through the glass canyons, alternating with “Join us! Join us!” Before long, riders were holding signs and banners lampooning the mayor -- “Koch Can’t Ride” -- and calling on New Yorkers to “Clear The Air: Cyclists and Pedestrians Unite!”

There were other actions too, most notably one at lunchtime in which cyclists snaked through the East 40s and 50s on foot to make the point that a midtown cycling ban would lead to sidewalk gridlock. It didn’t take long for the demonstrations to spill from the streets and into the media. Just as the rarity of lethal cyclist-pedestrian collisions in the early 1980s seemed to stoke press outrage when one occurred, the seeming incongruity of gritty bike messengers stopping at crosswalks and demanding safe streets and clean air ignited waves of coverage. Their prior unpopularity aside, the cyclists were photogenic and made good copy. Soon, each day’s Post, Daily News, and Newsday were plastered with pictures, columns and news stories reporting not just the latest protests but the treacherous conditions confronted by NYC cyclists and the “sweatshop of the streets” in which the messengers toiled. Before long, columnists were quoting cab and truck drivers who regarded bike messengers as fellow working stiffs, and occupational hazards like “dooring” entered the city’s cultural lexicon. The lack of both workers’ compensation for messengers and safe bike lanes for everyone who ventured onto city streets on two wheels became concerns for many New Yorkers and, in the minds of some, issues to be remedied before trying a draconian bike ban.

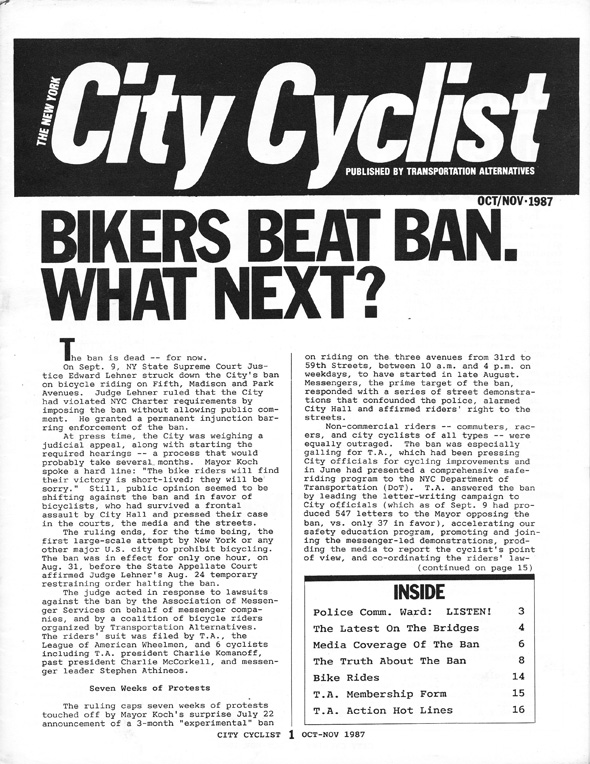

In late August, a New York State Supreme Court judge invalidated the ban on a technicality: the city hadn’t published official notice. The 45-day notice period meant that the ban couldn’t take effect until mid-October at the earliest, and City Hall threw in the towel. Press accounts credited the lawsuit, which had been mounted by Transportation Alternatives, but what gave the suit its legal standing and political currency was the “velorution” in the streets. Not only had Mayor Koch lost the battle of public opinion to the bicyclists -- over 600 letters defending them poured into City Hall -- but bicycling in New York City had acquired a human face, one that was exuberant, passionate and justice-seeking. Out-maneuvered in the streets and mocked in the media as Goliath beset by bike-riding Davids, the mayor who had entered politics as a liberal reformer quietly renounced his own handiwork.

Next week: The Rebirth of Transportation Alternatives