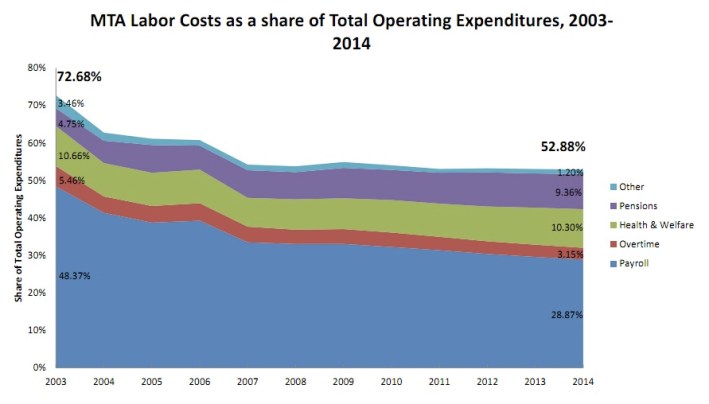

In 2003, labor costs dominated the MTA's budget sheets. Just under 73 percent of the transit agency's operating budget, which pays for day-to-day spending but not system expansions or major repairs, went to workers, according to a new analysis by the Regional Plan Association and the Empire State Transportation Alliance. By 2014, however, labor's share of operating expenses will have fallen to only 53 percent.

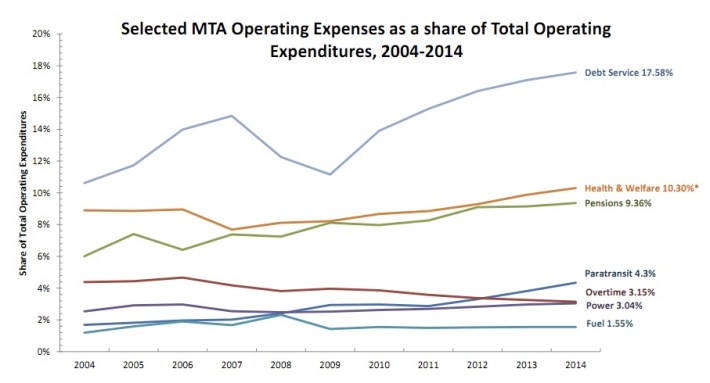

That won't be because total compensation, including rapidly rising health care and pension costs, has shrunk -- it hasn't -- but because the MTA is swimming in debt. Every year, more and more money that might go toward paying bus drivers, buying fuel, cleaning stations or keeping fares affordable is instead spent on debt service. Even over a period when pension costs will have risen by a billion dollars per year, it's debt that is chewing up the MTA's budget.

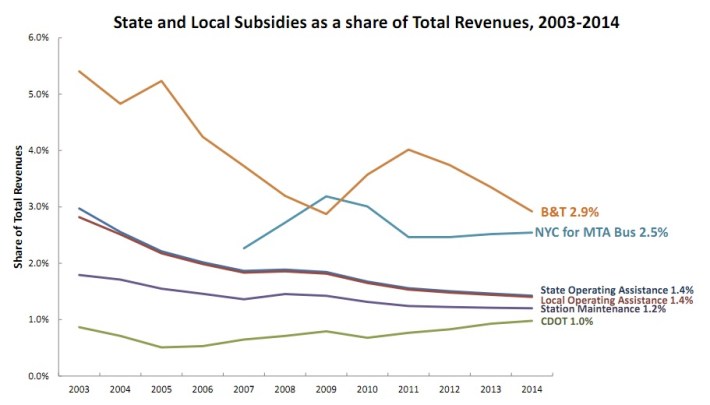

That debt is the outcome of decades of diminishing state support for public transit. After a major infusion of capital under the Hugh Carey administration, Governor Mario Cuomo cut all direct support for the MTA capital program. Though Cuomo found other revenues for the capital plan, notably by repurposing Westway dollars for transit, George Pataki just let those zeroes stand and put the cost of the capital plan on the MTA's credit card, starting the debt build-up in earnest. Pataki also started using dedicated transit funds to pay the state's commitments to the MTA, essentially double-dipping on those funds and costing transit almost $200 million a year.

The 2009 passage of the payroll tax helped the MTA's budgets significantly -- it is now the agency's largest dedicated revenue source -- but Albany's decisions to kill congestion pricing and bridge tolls meant that the MTA still had to borrow heavily to pay for repairs and mega-projects like the Second Avenue Subway.

The result is a massive run-up in debt. Though the MTA spent only $848 million on debt service in 2004, according to RPA, it is projected to spend more than three times as much, $2.67 billion, in 2014. Debt alone will eat up 17.6 percent of the MTA's operating budget by 2014; worse, RPA says that an alternative calculation shows the 2014 debt load at 23.1 percent of the operating budget.

When paired with the precipitous loss of revenues caused by the recession, it's no wonder that the agency was forced to implement historic service cuts and fare hikes last year. Nor does it help that the state and city's direct contributions to the operating budget aren't indexed to inflation; their real values decline every single year (of course, because of Pataki's double-counting, the state's operating assistance has essentially been flat at an effective zero).

This isn't to say that the right debt load is zero. That debt comes from paying for the MTA's capital program, which keeps the transit system in good condition and allows for expansion. It’s not unreasonable to shift some of the cost of debt service onto the operating budget, which is funded by fares, those ever-dwindling state and local subsidies, and by dedicated taxes, especially the new payroll mobility tax.

But the state government has left the last three years of the current capital plan almost entirely unfunded, boosting the debt load significantly. And no one knows how, or if, the next capital plan will be paid for. The fuse on the debt bomb is getting shorter all the time. In fact, it's already starting to go off.