The Department of City Planning's commitment to rezoning the city along more transit-oriented lines is a critical component of its sustainability agenda. Allowing more people to live and work next to transit means more people will ride transit and fewer will drive.

Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg and City Planning Commissioner Amanda Burden, upzonings have indeed been concentrated near transit. But what the administration gives with one hand, it takes with the other. Over the last decade, the Department of City Planning has also downzoned large swaths of transit-accessible land, preventing further development in these locations. Indeed, under one representative five-year period of Bloomberg and Burden's city planning, three-quarters of the lots rezoned for greater density were located within a half-mile of rail transit, but so were two-thirds of the lots where development was further restricted, according to research by NYU's Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy.

The pattern still holds. In fact, some of DCP's most recent rezonings are restricting development on blocks literally around the corner from a subway stop.

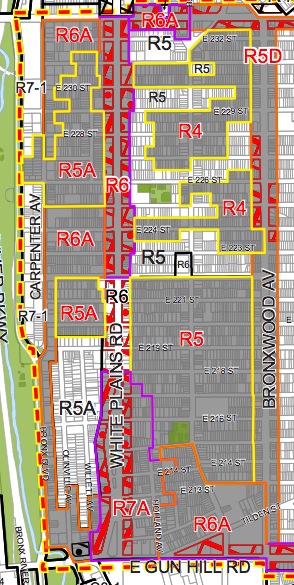

Take the Williamsbridge/Baychester rezoning in the Bronx, which the City Planning Commission certified last month. There, an elevated train, the 2, runs up White Plains Avenue. Along White Plains itself, DCP proposes to either maintain the existing rules or allow slightly more growth. But turn the corner off the main street even a fraction of a block, and the department is seeking to sharply curtail the opportunity for growth.

At the 219th Street station, for example, the allowable floor area ratio (or FAR), a measure of density, would drop from 2.43 to 1.25 as soon as you move east off of White Plains. Parking minimums would rise, requiring 85 parking spots for every 100 homes (up from a 70 percent ratio). To the immediate northwest of the station, the proposed zoning would be even stricter, with a FAR of 1.1 and a parking space required for each new residential unit.

The story is the same one stop further north at 225th Street. Walk one short block south of the station, turn left and the allowable FAR drops to 0.9, again with a parking space required for each unit.

Two sides of the Baychester Avenue stop on the 5 line are slated for the same extremely restrictive zoning, but in that case there won't even be any upzoning along a main street to compensate for it.

Those neighborhoods are in the northeast Bronx, near the end of the subway system. Even so, transit is heavily used in the area; in that City Council district, less than half of residents drive to work.

Moreover, DCP is tightening its zoning precisely because developers want to build in these areas. Explaining the need for the new restrictions, the department writes on its website that "the residential neighborhoods in the rezoning area have been experiencing development pressure" and that the new rules are needed to "preserve the scale and context of these areas."

Richard Gorman, the chair of Bronx Community Board 12, put it more explicitly. “We are all extremely excited about the proposed rezoning," he told the Bronx Times-Reporter. "We have low-density communities, and we would like to keep that character alive here.”

Surprisingly, City Planning claims that this rezoning is transit-oriented. Said DCP Commissioner Amanda Burden to the Times-Reporter, "In keeping with our commitment to transit-oriented growth, this rezoning would direct development away from residential side streets with small homes, to blocks than can accommodate new commercial and housing opportunities." DCP did not respond to Streetsblog inquiries for this story.

Williamsbridge and Baychester are far from exceptional cases. Another DCP proposal currently working its way through the public review process will change the development rules for Sunnyside and Woodside in western Queens. That plan includes some significant upzonings near transit, near the 40th Street 7 station, for example. But while DCP pushed for more growth near some rail stations, it proposed restrictions near others.

In the four-block area between the 65th Street station on the M and R lines and the 69th Street station on the 7, for example, DCP is seeking to reduce the allowable density of development while adding a requirement that all new residences include a front yard. The yard must be at least as deep as that of the yard next door and no less than five feet deep.

Every time the Bloomberg administration restricts development near transit, it means people who would want to live or locate businesses there cannot. The forestalled development will be pushed somewhere else, perhaps away from transit, out in the suburbs, or out of the New York region altogether. Those would-be transit riders will drive and New York housing prices will rise. It's hard to see how actively halting or shrinking development near transit squares with the goals of PlaNYC.