DOT needs to accelerate the build-out of the city's bike network in working-class neighborhoods outside the center city, say graduate students in the Hunter College urban planning department. They argue that expanding the geographic focus of the bike program would not only improve access to safe cycling for underserved neighborhoods, it might just help overcome the current backlash as well.

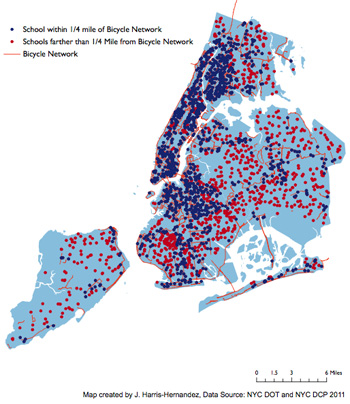

Unless the city devises a successful strategy to build bikeways in neighborhoods where bike infrastructure is scarce, the Hunter team writes in "Beyond the Backlash" [PDF], many parts of the city may get left behind for years to come. "A lot of the city isn't served as well by the bicycle network as the central business district and Downtown Brooklyn," said group member Jennifer Harris-Hernandez in a presentation at NYU on May 6. "This has reinforced transportation inequalities around race and class."

The Hunter team notes that the pattern of building the best cycling infrastructure near the city core may inadvertently give ammunition to opponents of bike infrastructure by overlooking the full breadth of New Yorkers. "Counting [working-class, outer borough] cyclists and planning with them in mind will create a more equitable and relevant network while countering recent claims that bicycling in New York City is for the privileged," they write.

To that end, the Hunter team proposes a geographic shift in focus for the DOT's bike program, paired with more intensive public outreach at the local level. At a moment when the city's tabloid press is launching weekly attacks on bike projects and local politicians seem to think they're doing constituents a favor by blocking plans for bike lanes, the Hunter team's report offers a thoughtful and constructive critique intended to strengthen the city's bike program.

The accelerated expansion of the bike network has built new bikeways in every borough and brought safer conditions to some low-income neighborhoods, but overall the city's bicycle planning has concentrated the most and best bike infrastructure in close-in, affluent neighborhoods. The bike network is at its densest and most interconnected in downtown Manhattan and northwest Brooklyn, and the overwhelming majority of the new protected lanes are located in high-income neighborhoods. While bike lanes serve many people who ride from outside the immediate vicinity, neighborhoods like Chelsea, the Upper West Side, and Park Slope are so far the primary beneficiaries of protected lanes and the robust pedestrian and cyclist safety improvements they produce.

There are good reasons for the bike network to be expanded this way. The roll-out of new bike lanes has tended to follow the path of least political resistance, at least in the short run. The Hunter team notes that the neighborhoods that have received the most bike infrastructure are the same ones that already had bike-friendly community boards or strong local advocates.

There are also technical explanations for DOT's current strategy. In explaining to East Harlem's Community Board 11 why that neighborhood wouldn't be receiving protected bike lanes last year, for example, DOT reps emphasized the importance of an interconnected bike network, which argues for extending bike corridors from the inside out. The city calculates that a bike-share program can succeed without subsidies if the stations are densely clustered in the central city, but a profit-turning system won't reach areas where bike-sharing can be most useful to low-income New Yorkers, the Hunter students note.

At a certain point, the Hunter team says, the lack of bike infrastructure in many parts of the city feeds into a vicious cycle. The full picture of the city's bicycle network "reinforces the impression that gentrification follows bicycle planning, and vice versa," they write in the report. "This practice, in turn, makes it more difficult for DOT to build outside the most bicycle-friendly community districts."

To escape this cycle, the Hunter students offered DOT a range of suggestions. Building local bike networks oriented around transit hubs mitigates the need for new bike lanes to be connected to the Manhattan network, for example. Integrating bike planning into a strengthened Safe Routes to School program could help spread safer infrastructure across the city while addressing the particular needs of young people and families.

They also urged DOT to change the tools it uses to measure cycling. The agency's focus on the screenline count, which measures the number of cyclists entering the Manhattan CBD, quantifies certain trips but ignores others (an issue which has also come up in the context of the screenline's divergence from Census counts). The screenline is "legitimating DOT's siting choices, so there's a cycle of counting and building in the same places," said team member Sam Stein.

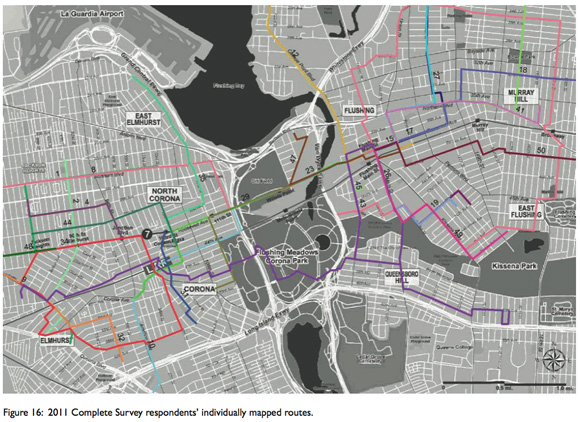

The Hunter team tried out ways to supplement the screenline count by surveying cyclists in Flushing, Corona, and Jackson Heights. One survey was placed on the handlebars of parked bikes in those neighborhoods. The respondents mostly did not bike into Manhattan, so they would never turn up in the screenline count. A majority responded in either Spanish or Chinese. These cyclists had a serious need for safety improvements -- 43 percent had been doored and 28 percent hit by a car -- especially on popular routes like Roosevelt Avenue.

Separately, the Hunter team recommended that DOT build stronger support for cycling by changing the way it integrates local groups, especially community boards, into the planning process. This call didn't come with any rose-tinted glasses about the current failings of some community boards. "Community boards can often be parochial, short-sighted, and not truly representative of the full breadth of the local community," they wrote in their report.

Even so, they argued, engaging more with community boards is necessary, especially given the strong likelihood that the next mayor will be more hesitant to support the expansion of the bike network. There is a need "to think beyond this administration and find community support for bicycle infrastructure," said Harris-Hernandez. Despite the anti-bike impression you might get from some southern Brooklyn community board votes, the Hunter team notes that there are plenty of local groups outside the central city who want to bring safer cycling to their communities.

There are already some good examples of innovative agency outreach for DOT to build on. The Hunter students point to the relatively smooth rollout of a transportation plan for Jackson Heights, arguing that the steady, long-term public outreach that accompanied that project paved the way for its success so far.

Part of the current problem, they say, stems from a lack of capacity at the community board level. Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer has proposed providing every community board with a trained urban planner, but in the absence of that, the Hunter team recommended that city agencies at least provide board members with regular trainings. "While this kind of work was begun with the 'DOT Academy' program," they note, "it seems to have fallen by the wayside."

The report suggests that bringing in community board members early on in the process, by inviting them to collect transportation data with DOT, for instance, can help overcome parochial concerns that too often obstruct change. Perhaps most importantly, Hunter identified groups like Make The Road New York, Desis Rising Up and Moving, and Queens Community House as eager to work with DOT on bike planning in their communities.