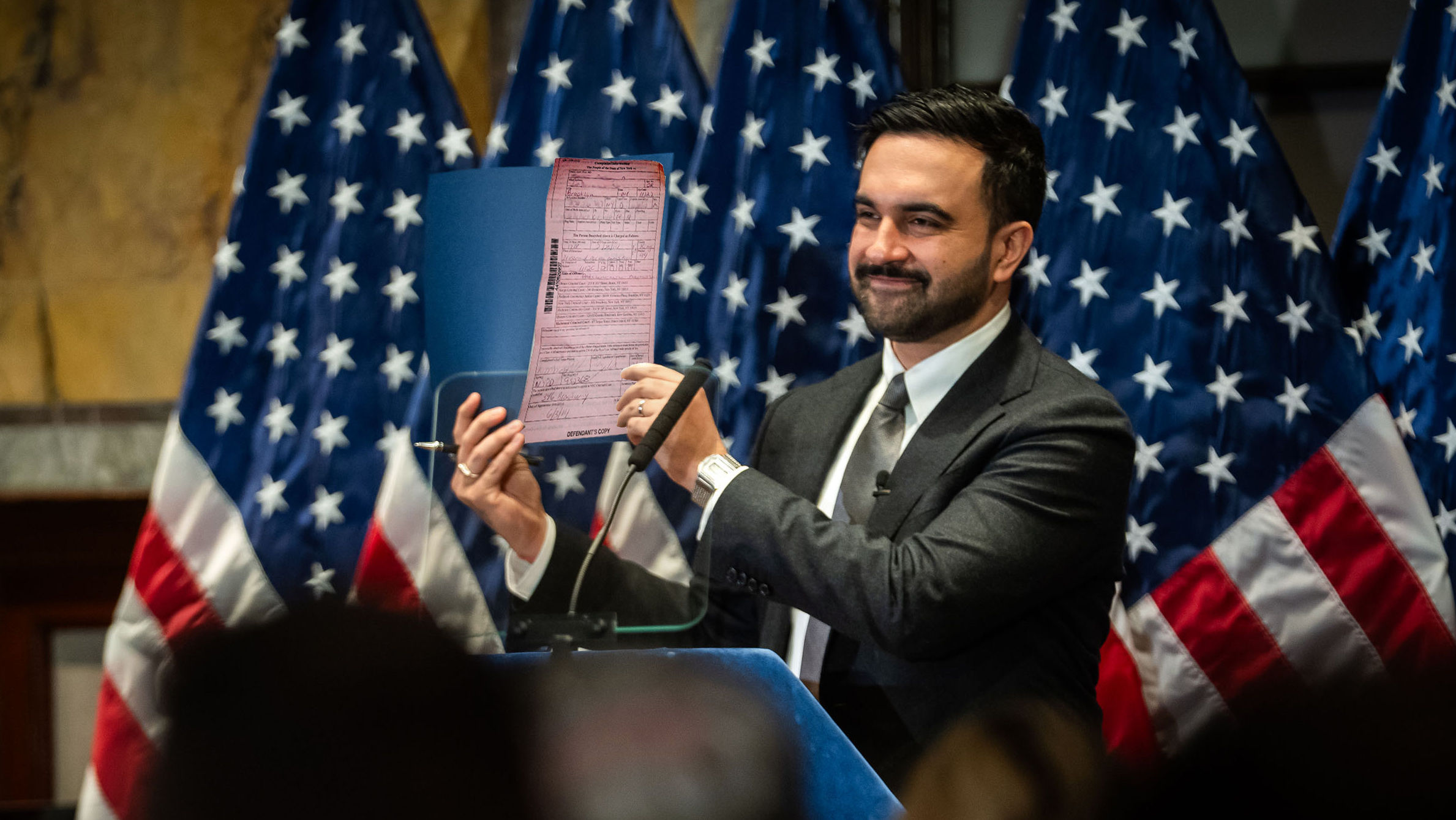

Jeff Geisinger's disorderly conduct summons.

Jeff Geisinger's disorderly conduct summons.When Jeff Geisinger biked through a red light on Atlantic Avenue last October, he knew that he might get a traffic ticket. So when a cop pulled him over, he wasn't surprised. He just didn't expect to be handed a summons for disorderly conduct, a criminal violation.

What Geisinger did wasn't legal and it wasn't the safest technique. Shortly after midnight on a Tuesday, he ran a red while biking north on Sixth Avenue in Brooklyn, at the intersection of Atlantic Avenue. "There was a stopped car to the right of me on Atlantic waiting to turn north," he said. "As the light turned red and I dashed through the intersection, the car slowly started to turn and I cut in front of it, with enough distance between the two of us for me to pass by safely." An officer saw the maneuver and pulled him over.

It's hard to imagine that what happened next would have happened to a motorist who did the same thing. Rather than write a traffic ticket, the officer issued Geisinger a summons for disorderly conduct.

While moving violations are non-criminal offenses, disorderly conduct is part of New York's penal code and carries a fine of up to $250 and up to 15 days in prison. It's something of a catch-all charge, probably by design, that can theoretically be invoked for "threatening behavior," making "unreasonable noise," using "abusive language" in public, or obstructing traffic, among other things.

Geisinger says that he didn't give the officer a hard time or make a scene, making much of the statute inapplicable to his situation, but not necessarily all of it. (The 77th Precinct has not returned Streetsblog's requests for comment.)

"It sounds strange to be charged with disorderly conduct for a moving violation," said Adam White, an attorney who has represented cyclists for more than 10 years. White cited a 2006 court case which determined that improper conduct must be "reinforced by a culpable mental state to create a public disturbance." If Geisinger wasn't intentionally trying to cause trouble, he probably shouldn't have been charged with disorderly conduct. White concluded that "the police officer did not have a reasonable basis for charging the cyclist" with disorderly conduct.

He added that the relevant question is how the law normally gets interpreted and applied. On that score, it's worth mentioning that Gus Gonzalez, the driver whom a witness saw intentionally knock a cyclist to the pavement on Ninth Avenue, causing severe bruising, is now facing a disorderly conduct charge as well.

We'll never know for certain if the charge would have held up in the city's justice system. In December, Geisinger went to court, pled not guilty and had his case dismissed when the cop didn't show up. He regrets being denied his day in court. "I wish I could have at least gotten in a sentence or two to state my case," Geisinger said, "but I silently accepted the dismissal and went home."