This essay is part of Streetsblog's "Car Harms" series, a package of stories designed to remind policymakers and the public of the hidden costs, dangers, inefficiencies and just plain old sadness that come from building our city around the needs of drivers. Auto-dependency has undermined the joy and beauty of our great urban spaces, and that must change. Click here to read the full series.

And if you are moved to make a small donation to keep series like these going in the future, please click here.

Automobile dependency and sprawl have made the costs of driving exceed its benefit. Here is research to prove it.

Conventional planning claims that wider roads, more parking and cheaper gasoline stimulates economic productivity, employment, incomes, economic opportunity and tax revenue. These assumptions could not be more wrong.

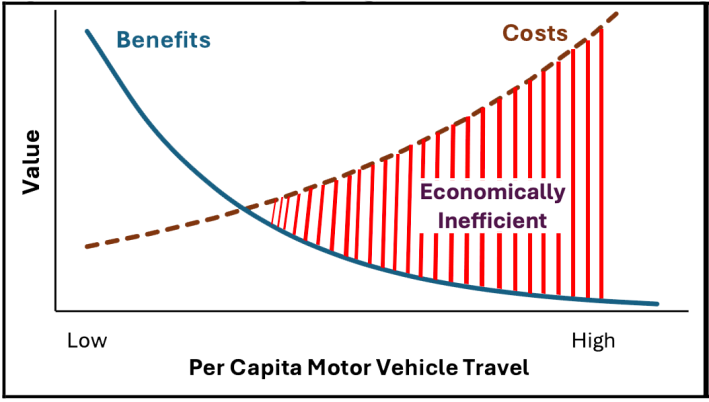

Some vehicle travel is very productive, but a growing portion is economically inefficient — its costs exceed its benefits. This reduces prosperity.

Let me share my new research, called The Mobility-Productivity Paradox, that investigates these effects.

The following graph shows a negative relationship between mobility (vehicle miles travelled or VMT) and productivity (gross domestic product or GDP) for U.S. states. Contrary to popular assumptions, productivity tends to decline as vehicle travel increases:

Productivity and Vehicle Travel for U.S. States

The following graph shows that productivity declines as urban lane-miles increase, indicating that expanding urban roadways is economically harmful. The statistical relationship is quite strong:

Productivity Versus Urban Lane Miles

The following graph shows that productivity tends to increase with urban density, an effect called agglomeration efficiencies. This indicates that policies that encourage compact development increase productivity, while those that encourage sprawl are economically harmful.

Productivity Versus Urban Density

Conventional planning assumes that traffic congestion is economically harmful and urban roadway expansions are economically beneficial, but the following graph indicates the opposite: productivity tends to increase with congestion intensity.

Productivity Versus Traffic Congestion

Similarly, businesses often claim that cities need more parking to attract customers and workers. In fact, the most economically successful commercial districts tend to have less parking supply and higher parking fees as indicated below. Reducing parking supply makes cities more prosperous by freeing up land for more productive uses and encouraging more resource-efficient travel:

Productivity Versus Parking Supply

Similar patterns occur at finer geographic scales. Productivity, employment, incomes, property values, tax revenues and innovation per acre tend to increase with development density and walkability. This reflects the value that residents place on convenient access to local services (shops, restaurants and schools) and the value of resulting transportation cost savings. The following heatmap shows the much higher property values in denser neighborhoods in Eugene, Oregon:

Land Value Per Acre Heatmap

So why does increased vehicle travel tend to reduce productivity?

Driving is expensive

For starters, driving is much more expensive than other modes, as illustrated below. Owning, operating and parking an average automobile typically costs $8,000 annually. I can report from personal experience living car-free in a walkable neighborhood can satisfy your travel needs for less than $1,000 annually. The high costs of driving reduce economic opportunity and productivity. For example, high vehicle expenses prevent some people from affording education that would increase their future productivity and incomes, and auto-dependent areas have high home foreclosure rates due to occasional financial shocks caused by vehicle failures, crashes and citations.

Typical Annual User Costs by Mode

External traffic costs

Second, vehicle traffic imposes various external costs on other people including infrastructure costs, congestion, crashes and environmental degradation. These costs filter through the economy as higher taxes, higher rents, travel delays, disabling injuries and lower property values. Driving imposes higher costs than other modes per passenger-mile, as illustrated below.Since motorists tend to travel far more miles per year than non-drivers, their annual external costs per capita are much higher.

External Costs by Mode

Reduced accessibility and non-auto mobility

Third, increased automobile travel creates automobile-dependent transportation and sprawled communities where it is difficult to get around without driving. Multimodal transportation planning expands the pool of potential customers and employees to include non-drivers. This increases employment and business activity, overall productivity.

Neighborhood accessibility and attractiveness

Finally, housing, retail, office, entertainment and tourist industries depend on attracting residents and customers which is affected by local environmental quality. Urban neighborhoods and commercial districts tend to be more economically successful if they are compact, multimodal and walkable, with less automobile traffic.

Businesses sometimes fear that streetscaping, bikeways, bus lanes and vehicle restrictions that will discourage their best customers by displacing parking spaces and reducing traffic speeds, but numerous studies find that such projects usually increase business sales and profits, indicating that reduced motorists’ convenience is more than offset by increased convenience for others. Business managers often overvalue customers who drive; non-auto customers tend to spend less per trip but shop more frequently and spend more in total than motorists.

The number of parking spaces lost is usually more than offset by shifts from driving to non-auto modes, reducing parking problems overall. For example, our bikeway network here in Victoria, B.C. displaced about 200 parking spaces but after the network was completed the city had 12,390 more bike trips, about 6,000 fewer personal vehicles, and 46,120 fewer car trips. The reduction in parking spaces was more than offset by the reduction in vehicles and trips.

Conclusions

This research suggests that current transportation planning is like medieval bloodletting, it applies misguided treatments that actually harm patients. It assumes that faster, cheaper and more vehicle travel is economically beneficial, but abundant evidence indicates the oppositive. This research shows that beyond optimal levels (about 4,000 annual vehicle-miles per capita, more in affluent rural and suburban areas, and less in cities and lower-income neighborhoods), most driving is economically inefficient: its marginal costs exceed its marginal benefits. This occurs because we underinvest in non-auto travel and underprice roads and parking, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of automobile dependency and sprawl.

Of course, some vehicle travel is very productive. Farmers, carpenters and visiting nurses can usually accomplish much more by using automobiles than other modes, but motor vehicle travel also imposes large costs to users (to own and operate vehicles), governments and businesses (for roads and parking facilities) and communities (from congestion, crash risk and pollution damages imposed on other people). Automobile travel also tends to displace other modes, reducing non-drivers’ mobility. As private motor vehicle travel increases, benefits tend to decline marginally while costs increase linearly, so a growing portion of driving has costs that exceed benefits, as illustrated below:

The message for businesses is very clear. Commercial districts tend to be most productive if they are compact and multimodal, with low vehicle traffic because that maximizes customer, employee, and freight access; creates environments that attract customers to visit and linger; and supports knowledge sharing and creativity, providing agglomeration efficiencies. Similarly, most individuals, particularly those with disabilities or lower incomes, are most productive if they locate in compact, multimodal neighborhoods with good access to services and jobs, which minimizes travel costs and ensures that they can reach services and jobs even when, for any reason, they cannot drive.