This essay is part of Streetsblog's "Car Harms" series, a package of stories designed to remind policymakers and the public of the hidden costs, dangers, inefficiencies and just plain old sadness that come from building our city around the needs of drivers. Auto-dependency has undermined the joy and beauty of our great urban spaces, and that must change. Click here to read the full series.

And if you are moved to make a small donation to keep series like these going in the future, please click here.

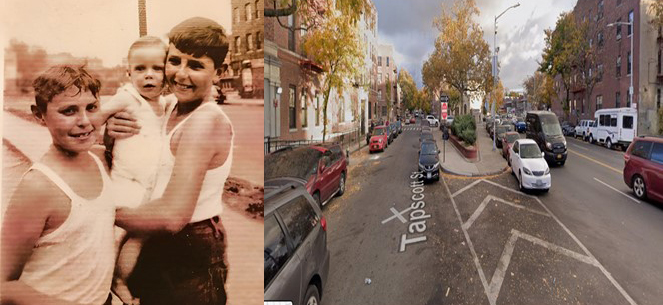

I love the picture below, taken in 1948, of my brothers Brian and Harold holding me in the roadbed of Tapscott Street at Howard Avenue, where we lived in Brownsville. Brian (left) was 10 and Harold was 12 (now both going strong at 86 and 88!) and I’m about 8 months. In the background is Howard Avenue, a wide and significant street that connects with Kings Highway.

What’s missing are cars.

And that explains why the Schwartz boys were in the street in the first place. My mother was the prototypical protective Jewish mama who would never let her babies do anything dangerous. But playing in the street wasn't dangerous in those days — a few years after the end of World War II, just before the car growth rate became astronomical in the region.

Before the car population boom, the “street,” aka the “gutter,” was our playground. And it was lost to the car in the name of progress and improvement. Let's look back.

The early 20th century

At the turn of the 20th century, the Bronx was still up; the Battery down and Park Avenue was a park, Fifth Avenue was a boulevard, and every East River bridge had trains and tolls.

Truly a 'Park' Avenue

I first came across the photo at right in Lost New York by Nathan Silver, a wonderful pictorial of buildings, plazas and streets that once graced our metropolis but have since vanished.

I was probably the New York City Traffic Commissioner at the time (it was the 1980s), and I was floored to learn that Park Avenue was once truly a park, complete with seating, stretching from Midtown to Harlem.

Today, the “park” in Park Avenue is long gone, replaced by a narrow median garden — designed for viewing but not experiencing:

Fifth Avenue was once 'Fifth Avenue'

During New York City’s “Golden Age” (roughly 1870-1910), Fifth Avenue was city’s grand boulevard, lined with wide sidewalks, stores and mansions. But in 1909, the city announced plans to widen the roadbed at the expense of the sidewalks, which the New York Times reported aptly: “The New Fifth Avenue” would become “New York City’s Greatest Driveway” — as sidewalks were to be narrowed by nearly eight feet on each side of the roadway to make way for two more lanes of car traffic.

"Probably no local improvement ... was ever received by the people most directly affected with so much regret as the widening of Fifth Avenue," the paper of record reported.

Fortunately, the Adams’s administration is looking to correct this blunder and restore the sidewalks to their 1900 widths. As shown below from a fall 2024 rendering, the sidewalks would be widened, trees would be planted, and pedestrians would resume their role as kings and queens of the street.

East River Bridges were all tolled

In the late 1980s, while serving as the city DOT’s Chief Engineer, I was reading an editorial in the New York Times written by the great urbanist Herb Sturz. The Williamsburg Bridge was in dire straits, and there was no money for repairs. Herb described a scene from A Winter’s Tale, Mark Helprin’s 1983 novel, in which the opening passage has a white horse silently crossing the snow-laden Williamsburg Bridge, passing the tollkeeper, asleep in his booth.

I called Herb to correct him — there were no tolls on the Williamsburg Bridge. Instead, he corrected me, pointing out that all four East River bridges were originally tolled when they first opened. His point was clear: had we kept the tolls, the bridge wouldn’t have been crumbling from lack of maintenance funds (it had been completely closed in 1988 due to a structural emergency).

Sure enough, there in the city’s records, I found a photo of the long-forgotten toll booth at the Queensboro Bridge. Crossing on a horse cost three cents; if you traveled in one of those new-fangled “auto-mobiles,” it would cost you a pretty dime!

The tolls were eliminated in 1911 by Mayor William Gaynor, who didn’t like the idea of charging people going from one borough to the next. Of course, he never met Robert Moses, who revived the practice with the Triborough Bridge, charging a quarter to cars in 1936.

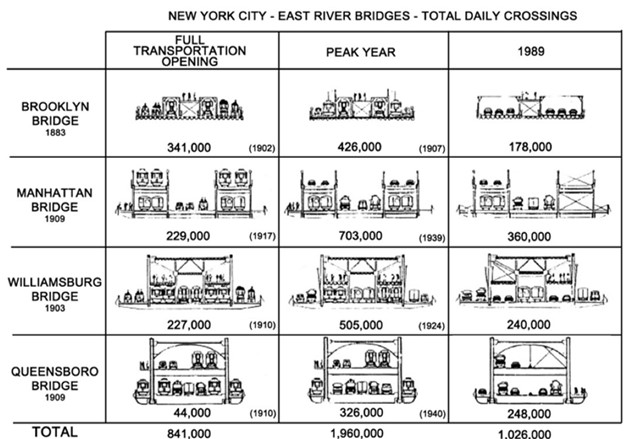

Those bridges once had 24 tracks!

All four bridges were originally designed primarily for transit: Brooklyn Bridge with four tracks, Manhattan Bridge with eight, Williamsburg Bridge with six, and Queensboro Bridge with six – totaling 24 tracks. Today, only six tracks remain: four on the Manhattan Bridge and two on the Williamsburg Bridge. In 1989, while at DOT, I looked at "persons carried" by each bridge over time and found that the “old” unmodernized bridges with rails carried nearly a million more people each day than the rehabilitated mostly trackless structures.

Streets are For People (especially kids)

I met David Gurin in 1977 while I was an engineer for the old Traffic Department. He had reached out to me after a go-between, Steve Jurow at the Natural Resources Defense Council, told him there was a guy at Traffic who’d could be trusted – someone who, in fact, was the “Deep Throat” providing NRDC lawyers Ross Sandler and David Schoenbrud with valuable information for their lawsuit to force the city to comply with the Clean Air Act and install tolls on the East River and Harlem River bridges.

The following year, Gurin became Deputy Commissioner for Planning at the newly created Department of Transportation and hired me as his Assistant Commissioner. Like me, he grew up in Brooklyn and recalled the days when the streets were playgrounds.

Conclusion

The message is clear: we have lost a great deal in our collective efforts to accommodate the automobile. We have lost so much that some can't even see it. Even old-line civic groups that plaster on their websites sepia-hued pictures of kids frolicking in the street in the 1940s end up putting the needs of car drivers over today's children — on the same website!

Fortunately, the pendulum is finally starting to swing back, and valuable public space is being restored to the people, albeit slowly.

The end result will be a healthier, happier, and more humane city.