The helicopter that broke apart mid-flight and plunged into the Hudson near Jersey City last week, killing the pilot and a family of five, flew more than 8,000 missions in the New York area during the last five and a half years, according to a flight history database compiled by the aviation consultancy FlightAware.

Virtually all of those “missions” were tourist joyrides — a frivolity for the holiday-makers on board, but an irritant or worse for the millions on the ground caught in the helicopter’s noise field.

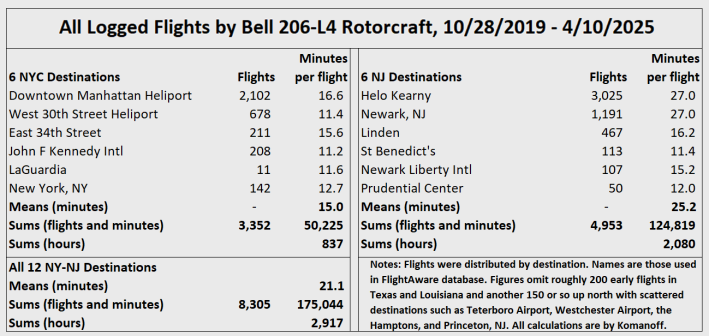

The ill-fated Bell 206-L4 Rotorcraft, denoted N216MH in Federal Aviation Administration records, was brought to our area from Dallas–Fort Worth in autumn 2019. Since then, its 8,305 area flights wreaked, in toto, $60 million worth of noise costs on area residents. That figure corresponds to the lost productivity, cognitive disruption, and vanished peace and quiet borne by people exposed to the machine’s roaring and thwacking.

My $60 million cost figure originates in an equivalence I posited nearly three decades ago when my lifelong friend and fellow mathematician, Dr. Howard Shaw, and I set about quantifying the noise costs of jet skis. From scouring the academic literature relating reduced property values to proximity to highways and airports, we created a formula: each 1 decibel increase in a neighborhood’s noise level above levels in otherwise comparable districts is associated with a 1-percent reduction in property values. (See Shaw’s and my year-2000 monograph, Drowning in Noise: Noise Costs of Jet Skis in the United States; the calculations for my $60-million figure appear below.)

In dollar terms, helicopter N216MH’s lifetime noise harm is close to last week’s loss of life. For decades, federal regulators charged with calibrating health and safety regulations have used in their calculations a benchmark known as the “value of a human life.” This exhaustively studied metric was set most recently at $13.6 million (in 2024 dollars). If we were to apply it to the six lives lost over the Hudson, we could say that humankind took an $80 million hit when the chopper split open.

It’s natural to recoil from these cold-dollar calculations, but they provide a certain clarity — or, at least, a fresh perspective. The calamity of six deaths in a helicopter turns out to be not markedly greater, dollar-wise, than the drip-drip-drip damage that the same craft’s continual racket exacted on millions of residents in five-and-a-half years of flying here.

And that’s just the noise from helicopter N216MH. Multiply its $60 million lifetime noise dis-amenity by the dozen or more tourist and commuter helicopters that ply our airspace each day (and throw in their air and climate emissions, to boot) and the conclusion is inescapable: the widespread and heartfelt distress over last week’s crash should extend as well to the noise and other helicopter-made pollution suffered daily by New York and New Jersey residents.

Methodology

From the FlightAware database, I was able to deduce that 60 percent of the 8,300-odd NY-NJ area flights terminated in New Jersey. The other 40 percent touched down at heliports in the five boroughs

I was also able to calculate that the New York-landing flights averaged 15 minutes duration, and the New Jersey flights 25 minutes. Applying an average flight speed of 100 miles an hour — adjusted from a standard 125-130 mph on account of the tourism angle — we see that the chopper flew a total of 300,000 or so miles in our area.

As shown in the table above, helicopter N216MH logged a lifetime total of 175,000 minutes in our airspace. I estimated a year ago for a Streetsblog post that helicopters caused $360 in noise costs per airborne minute, on average, to people on the ground who were caught in the noise field. Though they pertained to flights from the Manhattan West 30th Street heliport to JFK Airport, I believe they can serve as a starting point for noise costs of New York-New Jersey flights.

Here are my precepts and assumptions:

- Loud helicopter noise radiates audibly for a mile in every direction, creating a mile-wide “noise field.”

- A quarter of Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens households live within a mile of the 15-mile flight path, putting 625,000 households within the helicopter noise field.

- The average affected household is subjected to the noise for 44 seconds. That figure derives from an assumed seven-minute flight duration which translates to an average speed of 129 mph (calculated as 15 miles times 60 minutes per hour divided by seven minutes).

- During exposure. ambient sound levels in the noise field are elevated by 20 decibels on average.

- A “Noise Depreciation Index” of 1 percent, denoting a 1-percent reduction in property values — a proxy for noise annoyance — for each 1 decibel increase in noise levels above customary neighborhood levels. (The NDI applies only during the 44-second period in which the helicopter is audible.)

These assumptions resulted in a collective per-flight noise annoyance for the West 30th Street–JFK run of $2,538, calculated by multiplying 625,000 affected households x 1 percent NDI x 20 excess decibels x $1,200 monthly per-HH rent x 44 seconds of noise exposure divided by 2,600,000 seconds in a month. Applying that figure ($2,538) over a 7-minute flight yielded a noise cost per minute in the air of $363.

For the doomed helicopter, I multiplied $363 per minute by the 175,000 total minutes it was airborne over NY-NJ from the time it arrived here in 2019 until last week. The result: $63.5 million.

What you can do right now

As I wrote a year ago, the best weapon by far for throttling helicopter noise is to tax the hell out of it. And the gold-standard bill to tax helicopter noise remains A2583, the bill written by Albany’s foremost exponent of externality pricing, Brooklyn Assembly Member Robert Carroll (D–Park Slope).

Carroll’s bill would impose a noise charge of $100 per occupied seat or $400 per flight, whichever amount is larger, on any non-essential helicopter flight from, to or over New York City — a category that excludes medical, law-enforcement or emergency operations but includes sightseeing and “commuting.” I estimated in my year-ago post that Carroll’s noise fee, passed along to would-be customers, would cut helicopter use by 30 to 50 percent — a terrific bite out of the (noisome) apple.

Gov. Hochul's support for congestion pricing suggests that she recognizes the concept of using pricing to change one person's behavior that undermines other people's quality of life. But the governor has not signed off on Carroll's bill. I hope you'll join me in calling or emailing Hochul’s office to beseech her to add A2583 to the budget and finally bring helicopter noise in New York City under a modicum of social governance.