Congestion pricing is coming, and Upper West Siders are fretting about a supposed “parkmageddon” caused by drivers who want to avoid paying a toll to enter Manhattan’s Central Business District. But the parking crunch in residential parts of Manhattan long pre-dates the as-yet-unimplemented tolls.

The real villain: Most curb parking is free.

On the Upper West Side, that means that 222,000 residents competing for 12,300 free curb parking spaces — 18 residents per free parking spot (and that's not even taking into account the nonresidents who want to park at the curb when they drive to the Upper West Side to work, shop, dine or deliver packages). Drivers who compete for the scarce curb spaces circle the neighborhood hoping to see a car pulling out. Finding a curb space is, in the words of Borough President Mark Levine, “a brutal and time-consuming process.”

Parking reforms are difficult. In a dense neighborhood where residents greatly outnumber curb parking spaces, only a tiny minority can park a car on the street. Nevertheless, this small-but-vocal minority can take over any public meeting and create the impression that everyone wants free parking — as I witnessed when I attended an Upper West Side community board meeting earlier this month. Elected officials who even consider charging for curb parking probably see it as political suicide.

“Free parking for automobiles is an absolute right anywhere there are automobiles — which is to say everywhere,” one attendee at another meeting claimed. This language exemplifies the "paid parking derangement syndrome" — the onset of extreme paranoia in reaction to the prospect of paying for parking, leading the afflicted person to speak in exaggerated language and lose touch with reality.

A six-month study of a 15-block area in the Upper West Side found that searching for free parking created 366,000 excess vehicle miles traveled annually. The cruising cars congested traffic, polluted the air, and emitted 22 tons of carbon dioxide per block per year.

Charging the right prices for curb parking can remove the incentive to cruise for it.

What does "the right price" mean? The right prices for curb parking are the lowest prices that leave one or two curb spaces open on every block, so the curb lane is well-used (most spaces are occupied), but readily available (a few spaces are open). Goldilocks parking prices (not too high, not too low) eliminate the need to cruise for curb parking.

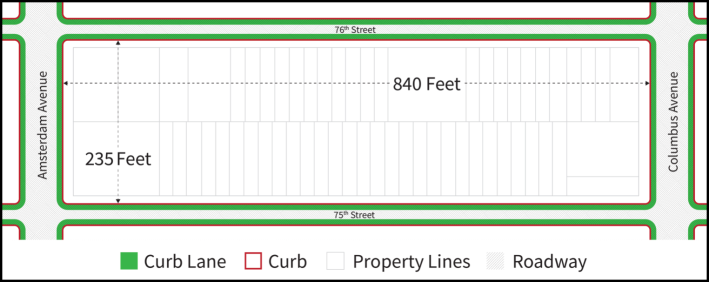

To defuse political opposition to paying for curb parking, some cities have established Parking Benefit Districts that spend the meter revenue to pay for public services on the metered blocks. To understand how this would work in the Upper West Side, consider the block surrounded by 75th and 76th streets between Amsterdam and Columbus avenues.

The block has 1,030 residents and 72 unmetered curb spaces, so there are 12 residents per unmetered space. The parking spaces at the ends of the block on Amsterdam and Columbus avenues are metered at $4 or $5 an hour. If the city begins to charge $5 an hour for the unmetered spaces on 75th and 76th streets, the new revenue will be about $1.1 million a year — enough to pay for free public transit for all the block’s residents.

Free transit for all the residents can create political support for metering the free parking spaces. The MTA will receive the revenue to pay for the residents’ rides, and the residents will ride transit more often. When both the sources and the uses of the revenue are considered, priced curb parking looks reasonable and fair.

There are other ways to spend the meter revenue in a parking benefit district. To get the piles of trash off New York’s sidewalks, meter revenue can be used to accelerate the city’s plan to install large waste containers in the curb lane and empty them frequently. The curb lane will lose a few parking spaces, but the clean sidewalks will improve life for everyone.

Advocates for parking say that free parking is more equitable than priced parking. This is a selfish appropriation of the very notion of equity.

Free curb parking has a veneer of equality, but it is unfair for two reasons: First, 73 percent of households on the Upper West Side do not own a car and they get no benefit from free curb parking. Second, car-owning households have almost double the annual incomes of car-less households. The wealthy get most of the free parking, and the poor get almost nothing. Public services such as transit benefit working people far more than free curb parking does, and parking benefit districts can manage the city’s curb lanes to serve everyone.

What Niccolò Machiavelli wrote in the 16th century applies perfectly to parking benefit districts in the 21st century:

There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in introducing a new order of things. The innovator has enemies in all those who profit by the old order, and only lukewarm defenders in all those who would profit by the new order. This ambivalence arises partly from … the incredulity of Mankind, who do not truly believe in anything new until they have experienced of it.

To overcome this incredulity, New York can create a pilot parking benefit district on a few blocks in one neighborhood. If the pilot program is a success, the residents of other blocks can vote to join the district in a democratic, opt-in process. The Department of Transportation can meter the now-unmetered curb spaces and deposit the revenue in a lock box reserved for free transit passes or other authorized local expenditures in the parking benefit district. Public services financed by the meter revenue will reveal the high cost of free curb parking.

Crowded curb parking is a great opportunity disguised as an insoluble problem. Almost like urban alchemy, parking benefit districts can transform a parking shortage into public services. Such districts can be politically popular, financially successful, environmentally sustainable and socially just.

Finally, here’s a thought experiment: If you live on the Upper West Side, would you prefer free public transit or free curb parking on your block? If you don’t own a car or park off-street, you will probably want free public transit.

Why not give a parking benefit district a try?