ALBANY — Wait 'til last year!

Advocates trekked to the State Capitol to lobby lawmakers for a slate of street safety bills, including permission for the city to set its own speed limits, that failed catastrophically last year despite a 100-hour hunger strike by the mothers of two road violence victims.

This year's version of the annual rite of passage — or, in this case, lack of passage — occurs with no guarantee that things will be different this year for the livable streets movement. Last year's legislative session ended as one of the worst on record, thanks in part to Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie's refusal to allow Sammy's Law, which the majority of lawmakers support, to be voted on amid concern from a small number of members in the lower house.

On Tuesday, as victims families fanned out across the Capitol, the still-powerful pol declined to say whether he would allow the speed limit reduction effort to succeed this time.

Just as she did last year, Gov. Hochul included Sammy's Law in her executive budget, but there's no indication of how the governor will prevent the legislature from again slicing it from the financial document and simply acting (or not acting) on the measure like a normal bill.

The hunger strike and masses of support didn't convince Heastie last year, so it's unclear what will change this year. And Hochul spokesman John Lindsay didn't say why this year would be different, merely saying that “Gov. Hochul ... will continue pushing for the passage of Sammy's Law in this year's budget.”

Brooklyn Assembly Member Emily Gallagher, a strong Sammy's Law supporter, is hopeful, but then again has seen things go south before.

“Last year, the conversation was somewhat of a nonstarter,” said Gallagher. “Even [lawmakers] who had City Council members from their districts supporting the bill were still not interested in supporting it.

“I find it fascinating how personally people take driving,” Gallagher added, without naming names.

Last year marked one of the deadliest in the Vision Zero era, with 249 people killed on the city’s roads, and tens of thousands of injuries. One Queens lawmaker joined those ranks two weeks ago when she was struck by a driver and suffered a broken arm.

Queens Assembly Member Jessica González-Rojas, who was a Sammy's Law supporter before she was run down, said she hoped to share her experience — and those of families who’ve lost loved ones — with her fellow electeds.

“I’m glad I’m just a crash statistic and not a death statistic,” González-Rojas told Streetsblog, her arm still in a sling. ”I’m glad to be here, but had the car been going faster ... I might not be here.”

Lower speed limits do indeed save lives: There was a 36-percent decline in pedestrian fatalities after the city got permission in 2014 to lower its speed limits from 30 miles per hour to 25, according to city data.

Last year Albany passed zero street safety bills and we lost over 700 New Yorkers to traffic violence on our streets.

— Transportation Alternatives (@TransAlt) January 23, 2024

This year @GovKathyHochul announced she will include Sammy's Law in her proposed state budget.

No more delay. Lives depend on this. https://t.co/bL6x2OYrr6

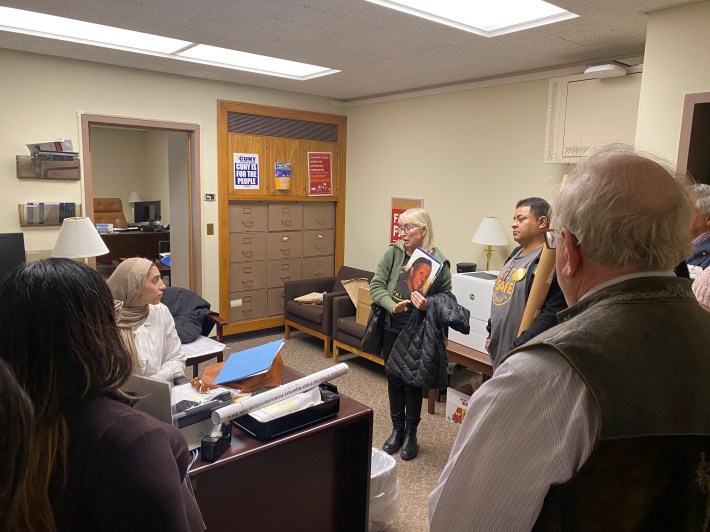

At a rally outside the Assembly chamber on Tuesday, activists refused to engage in negative thoughts.

“We have spent a lot of time building support across the city for Sammy’s Law,” said Amy Cohen, co-founder of Families for Safe Streets, whose 12-year-old son, Sammy Cohen Eckstein, was killed by a driver just steps from his Brooklyn home in 2013. “We have organizations from across the city supporting Sammy’s Law, building support, talking to legislators who had concerns. A lot of it was misunderstandings and I think we’re going to get there this year.”

Cohen produced pages and pages of names of supporters, plus a list of three dozen organizations that joined the fight in the last month.

In addition to Sammy's Law, activists hope to pass a package of bills that includes:

- Requiring transportation departments to consider complete street designs for road projects, including better access for pedestrians, cyclists, people with disabilities, and public transportation.

- Allowing the Idaho Stop, where cyclists can treat stop lights as stop signs, and stop signs as yield.

- Requiring speed governors for drivers who get 11 or more points on their license over 18 months, or were caught by cameras breaking the speed limit six or more times in a year.

- Doubling the funding for complete streets from $5 million to $10 million.

- Reauthorizing the city’s 30-year-old red-light camera program and expanding it from just 150 intersections to 1,325 crossings, about 10 percent of the city's intersections