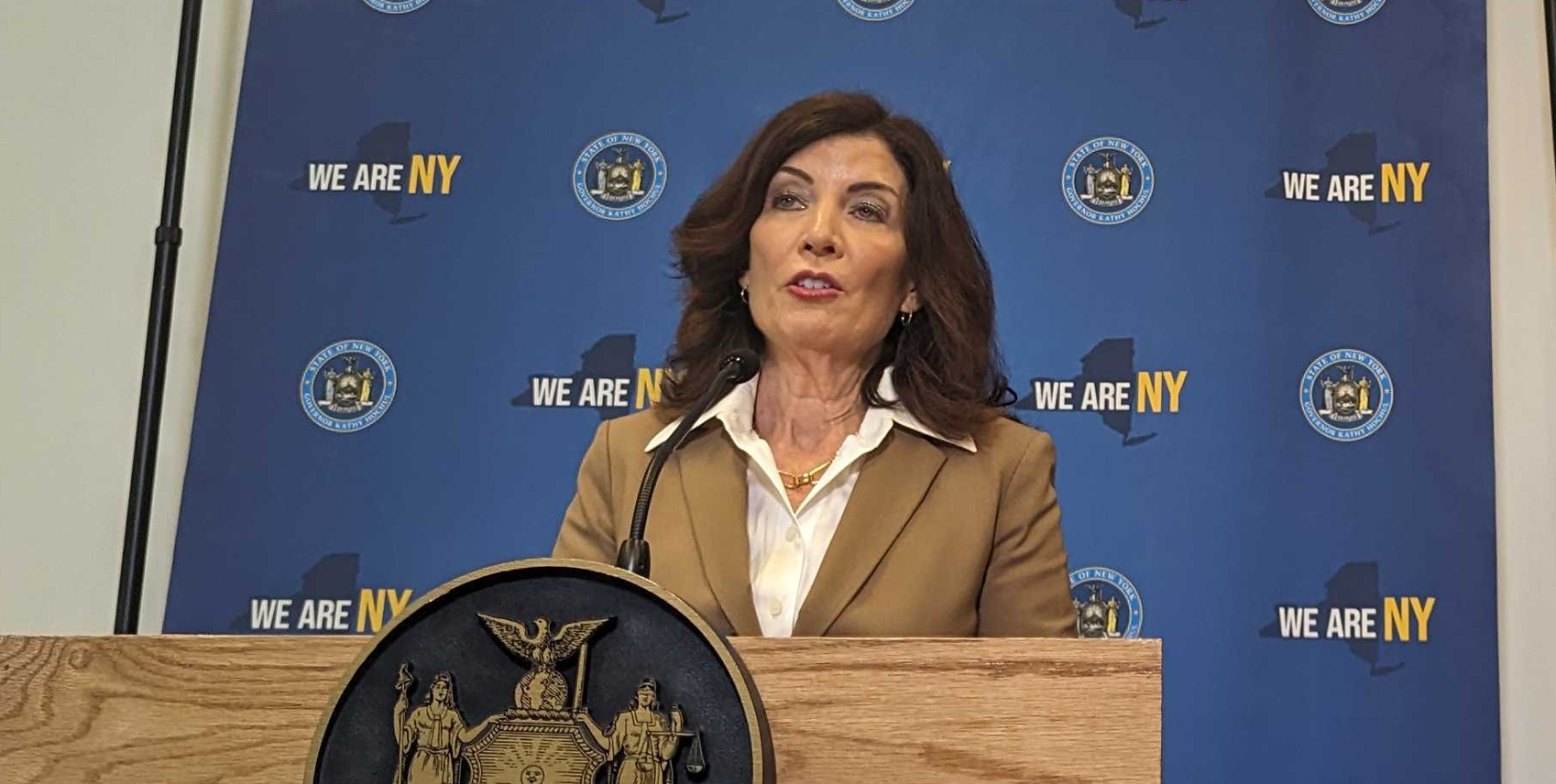

Gov. Hochul has a message for drivers upset over New York City's congestion pricing now that the program finally has the green light from the feds: ride the frickin' train.

"More vehicles have come back than we had even before the pandemic. Now, that's a sign of life, but these vehicles have another alternative — an incredible alternative — called public transportation," Hochul declared at a rally on Tuesday to celebrate the Federal Highway Administration's official approval of the MTA's environmental review of the tolling program.

"We're more cognizant of what's going into our lungs these days [as] we're experiencing the effects of the wildfires in Canada. What about the wildfires that are happening on our own streets right here, coming out of the exhaust pipes of all these vehicles?" the governor said, in reference to poor air expected to hit the region again on Wednesday.

"It doesn't have to be this way. That is the good news. This does not have to be our destiny, New York, and it's not going to be any longer."

.@GovKathyHochul kicking off congestion pricing announcement at NYU. As @ReinventAlbany says, the Gov hasn’t flinched once in the face of the (typical) knuckleheaded stuff that came out during last summer’s comment period, nor the dumb hypocrisy coming from her NJ counterpart https://t.co/rIbl39FxhV pic.twitter.com/8NIgQB1oY4

— Jon Orcutt (@jonorcutt) June 27, 2023

Former Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the State Legislature passed congestion pricing in 2019 to help fund $15 billion of the MTA's $55-billion capital program. Initially expected to launch in late 2020 or 2021, the program has faced years of delay — first by the Trump administration and then by a requirement that the MTA conduct a 16-month environmental review of every potential impact of the program.

The FHWA's "finding of no significant impact" from the tolls marks the culmination of a 15-year effort to get road pricing implemented for the busiest part of Manhattan. Multiple efforts in the late 2000s by then-Mayor failed to materialize. In 2013, a new coalition proposed the "Move New York" plan that eventually became congestion pricing, but the proposal didn't gain significant momentum until the subway's "Summer of Hell" in 2017 made the transit system's maintenance needs impossible for politicians like Cuomo to ignore.

Federal approval means the toll on car trips in Manhattan below 60th Street is on pace to start in the spring of 2024, according to the MTA's timeline — barring legal challenges or other inevitable obstacles. New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy has retained former Deputy Mayor Randy Mastro to explore "all possible legal options" to stop the program, according to reports.

Some potential legal challenges may have been preempted: The MTA's initial environmental study anticipated increased truck traffic through Bronx communities already plagued by bad air quality; the updated assessment released in May proposed tens of millions of dollars in spending to mitigate and address the borough's environmental concerns, as Streetsblog's Dave Colon reported exclusively.

"This is a win for environmental justice," said U.S. Rep. Ritchie Torres (D-Bronx), who led the outcry when the draft review forecasted increased pollution in his district.

Hochul, who hails from suburban Buffalo, opted to pursue the toll plan despite having inherited it from her disgraced predecessor. On Tuesday she declined to criticize Murphy or disclose the state's legal strategy going forward. The governor deferred to the Traffic Mobility Review Board — which she controls thanks to appointing the majority of members — when asked by reporters about the dozens of proposed toll exemptions floated at public hearings on the plan.

"Everything we're doing here is for the benefit of New Yorkers and people in the entire region. Twenty-eight million people will benefit from the investments that we're going to continue to make — not just for New Yorkers, but the entire system that serves the neighboring states as well," she said.

The TMRB may ultimately have its hands tied when it comes to setting tolls and creating exemptions: The 2019 legislation requires the program to raise $1 billion annually, so any revenue lost to exemptions will have to be made up for through higher tolls on everyone else. MTA board members will vote on the TMRB's recommendations.

And almost every driver wants an exemption. Tiffany-Ann Taylor, the Regional Plan Association's Vice President for Transportation, said she expects the TMRB to give the public a chance to weigh-in, but less than was offered during the environmental review period.

“My gut tells me there’s probably going to be two, maybe three meetings if they’re ambitious. That will be an opportunity for folks to give public testimony in person," Taylor said.

“The MTA board will vote yay or nay on the TMRB’s recommendation. We still don’t know how much it will cost; we only know that there is a range of possibilities right now between $9 and $23.”