It was the best of stations; it was the worst of stations.

The JFK AirTrain has two terminal stations — one at Howard Beach and the other at the Jamaica Long Island Rail Road hub. They both serve thousands of tourists and workers, both are run by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and both play a key role in getting people to and from the airport without adding congestion and pollution to the clogged roads and skies of New York City.

But one station — the one in Jamaica — is an affront to transit, and basic decency (and that's ignoring the idea that what should be a free service in fact costs $8.25 — much more than an off-peak LIRR City Ticket to Jamaica from Penn Station or Grand Central).

At Jamaica, travelers get the sense they are completely unwelcome in the 20-year-old terminal. As you can see in the photo below, passengers are treated like cattle, thanks to barricades that reduce the space by half:

Any deviance from Port Authority-approved movements is also discouraged by the lack of public seating and by the numerous signs warning users against “laying down or sitting on the floor in the building … including sitting on your bags or any other objects you use to sit on.”

“These aren’t really serving a purpose," said one airport traveler who declined to give his name. "I don’t see what purpose they serve.”

It's a striking change from the way the station used to be, as shown in photos from one of the station's architecture firms, when the station was much less constrained and hemmed in, with ample room for passengers and luggage. No public areas of the station were arbitrarily blocked off:

When it opened, the station had an area occupied by airline check-in counters, but those were removed in favor of food vendors. But over time, those food areas were also made less inviting to people.

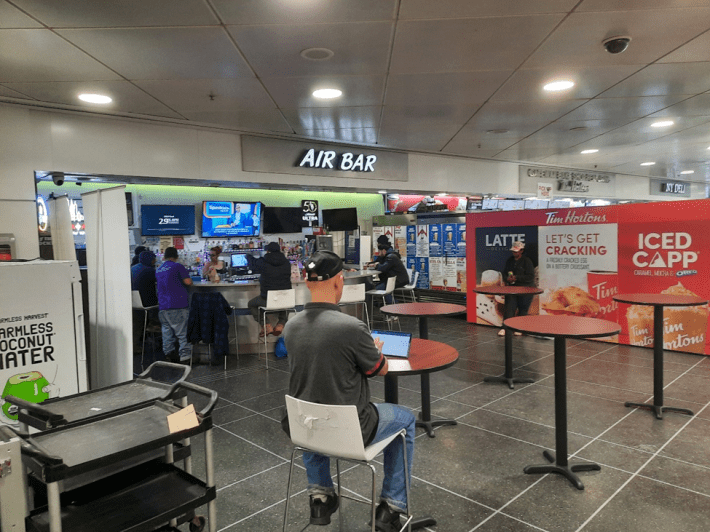

The photo below, taken for a 2017 article for Untapped New York, shows ample seats and tables in front of Air Bar, one the main food vendors in the station. The seats and tables, clearly, are being used, laid out in a way that doesn’t discourage their use. There are even, as you can see, seats:

But now, the only seats are high bar chairs, one of which occasionally makes it over to the standing high-top tables that are otherwise rarely used — and when they are, only briefly, given the lack of seating, comfortable or otherwise.

These changes are selective, as they are absent from the AirTrain's other terminal at Howard Beach. It's by no means the Komsomolskaya Station in Moscow, but at least there aren't barricades. And at least there are two benches.

This Dickensian tale of two stations raises questions about why the Port Authority (which declined to comment for this story) is making the Jamaica AirTrain hub so much less inviting than its Howard Beach counterpart.

One reason is clear: The agency is willfully discouraging unhoused people from congregating in the station; the result is that public infrastructure used by everybody has become much less pleasant.

The AirTrain station area is the only part of the concourse that’s climate-controlled, leading to unhoused New Yorkers using it for rest, according to Saff, the manager of the Tim Horton’s and NY Deli food outlets in the station.

“In the wintertime there were so many homeless people here," he said. "I don’t know why they put [the barriers] in, but it’s maybe related to that.” In fact, the barriers exist in such numbers only in that part of the station complex.

Nonetheless, this policy is a clear failure in that unhoused New Yorkers still find refuge in the station (on a recent visit, a homeless woman who was sitting against a barricade declined to comment).

Is there an element of racial and class bias in the Port Authority's varying conditions? Jamaica is 13 percent white, while Howard Beach is 60 percent white, according to census figures. And Jamaica's poverty rate is double that of Howard Beach. Numbers don't tell the full story, of course, but at the very least, it’s worth discussing why the station in the mostly Black and Latino neighborhood is in worse condition than the one in the mostly white neighborhood.

But perhaps that's by design. In a world where "subway crime" is a talking point (even when incidents are few), barricades enforce the idea that transit should be viewed with caution and concern — a very disturbing message being sent by a transit agency that, presumably, wants people to use the system.

No one wins when public space is made less inviting to the public, housed and unhoused alike. And the murder of Jordan Neely has rightly triggered discussions about how the state unfairly treats its most vulnerable citizens and also how public space like the AirTrain station in Jamaica has been made undemocratic in who gets to use it and how.