Less parking = more housing.

The city should dramatically reduce the amount of car parking it requires developers to build because doing so will result in more much-needed affordable housing quickly — a new report released Tuesday by the Regional Plan Association concludes.

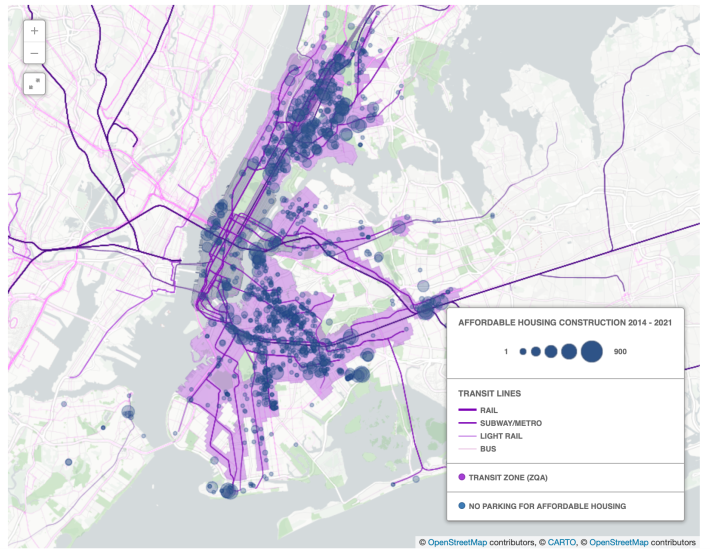

A trio of housing experts and urban planners at the RPA analyzed data from thousands of new housing units built across the five boroughs before and after a 2016 zoning change that eliminated the mandatory minimum parking rules in transit-rich areas, and found that more units were created in areas where the minimum requirement had been waived.

“The big takeaway is that we can really get more affordable housing by doing smart things with parking and land use in the city,” said RPA’s Moses Gates who wrote the report with Marcel Negret and Lindsey Hover. “We can incentivize a lot of it by just being smarter about what our requirements for parking are.”

The report, “Parking Policy is Housing Policy,” comes amid Mayor Adams’s new "City of Yes" zoning vision, which included a new provision to “prioritize people over parking to make streets safer, and reduce requirements to enable more of the housing, services, and amenities that help neighborhoods thrive” — a crucial goal in a city where more than half of households do not have access to a car, and where nearly half said in a recent survey that they believe that the key to addressing inequality is providing people with a roof over their head.

NYC has already waived parking minimums in certain areas through the 2016 Zoning for Quality & Affordability initiative

— Regional Plan (@RegionalPlan) December 6, 2022

In these areas it's yielded more overall housing production, a larger share of affordable housing, and more projects on small lots

📝 https://t.co/D4W1JTSqCK pic.twitter.com/gI0MaIeToM

Forcing developers to build more parking causes myriad deleterious health impacts to neighborhoods, like more congestion and pollution, but it also raises the construction costs that are passed along to tenants, experts say. Multiple studies show that including parking in new developments could cost thousands more, about $1,700 more per unit per year.

The first parking minimums were written into the city’s zoning laws for residential buildings in 1950; and the rules were amended in 1961 to include commercial and mixed-use buildings. The exact number of off-street parking spaces currently mandated for new developments is based on the use of the building, and the zoning district in which it sits.

In the decades since, the requirements have been relaxed; in 1982, all parking minimums were eliminated in Manhattan below 96th Street on the East Side and below 110th Street on the West Side (in response to the 1970 Clean Air Act); they were later reduced in Downtown Brooklyn and parts of Long Island City; and in 2016, the city’s Zoning for Quality and Affordability plan eliminated parking minimums for fully affordable housing developments in transit-rich areas, which typically means within a half-mile walk to a transit option; and the city also lowered or eliminated parking minimums for new developments as part of some neighborhood-wide rezoning plans such as for Inwood.

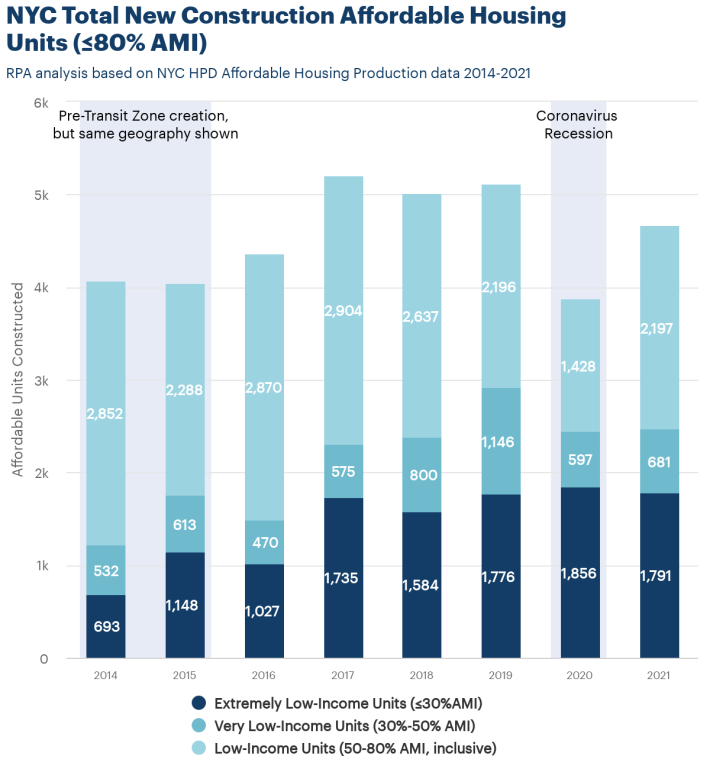

The RPA analyzed new housing units built across the five boroughs before and after the 2016 changes, as well as new construction that relied on a federal tax credit called the Low Income Housing Tax Credits, which typically facilitate smaller buildings, not skyscrapers.

The trio found that between the enactment of the Zoning for Quality and Affordability plan and the start of the Covid-19 pandemic — which halted all development — the number of new affordable housing units built in transit-rich areas increased by 36 percent compared to before the ZQA.

And specifically, it spurred an increase in units at the deepest affordability levels — 50 percent of the area’s median income (AMI) and 30 percent AMI — by 64 percent and 63 percent, respectively.

As a result, the RPA is now calling on the Adams Administration to go a step to facilitate more affordable housing development, following the lead of other cities around the country that have already eliminated parking minimums across the board. For example, Buffalo did away with its parking requirements in 2017, San Francisco in 2018, Minneapolis in 2021, and most recently, Boston did last year for affordable housing developments as well as neighboring Cambridge this past October, which removed parking requirements for all new buildings, not just those containing residential or affordable housing.

The RPA did not go so far as to recommend a wholesale elimination of parking requirements — which has already been proposed by state lawmakers — but it does call on the city to expand the boundaries of the so-called transit zone, including all of the additional areas that had been left out of the initial 2016 change that are still served by mass transit.

It also asks the Adams administration to include all market-rate housing in the types of developments currently exempt from parking minimums. And lastly, it suggests modifying zoning incentives to encourage more affordable and senior housing.

“This is not final steps. We want to recommend that we build on what we have seen be successful and how far that could go,” said Gates. “I don't think we would be opposed to expanding the recommendations on parking requirements in the future beyond what they are right now.”

The Department of City Planning embraced the report, agreeing that much more must be done to ensure adequate affordable housing gets built to reduce the city’s housing crisis.

“When we put people before parking, we help put roofs over the heads of New York families, we bring down the rent, and we make our city greener and safer,” said Daniel Garodnick, who chairs the City Planning Commission and is the Director of the Department of City Planning.