Starting on Wednesday in New York, Transportation Alternatives will host its annual “Vision Zero Cities” conference. In conjunction with the confab, Streetsblog is posting content from the annual journal published by TransAlt. We’ll roll them out over the course of the week. Meanwhile, click here for the full conference schedule and to register.

Nearly every city has a “boulevard of death” — a too-fast, too-wide street notorious for being the site of recurring traffic fatalities and serious injuries. From Philadelphia’s Roosevelt Boulevard to Hillsborough Avenue in Tampa, these are streets designed for cars to traverse busy neighborhoods at highway speeds. Transportation agencies call these streets arterials, but these auto-oriented thoroughfares are also spines of urban life: they are places where people live, work, take the bus, go to school, and shop.

In urban areas, arterials make up just 15 percent of all roads but are where a whopping 67 percent of pedestrian deaths occur.

In Philadelphia, an average of 28 people were killed or seriously injured each year on PennDOT’s Roosevelt Boulevard from 2013 to 2017. In Tampa, an average of 29 fatal or serious injury crashes occurred each year on FDOT’s Hillsborough Avenue between 2014 and 2018.

On arterials, as is the case across the U.S., fatalities are increasing most sharply among people walking and biking. In preparing its Vision Zero Action Plan, the City of Tampa found that 78 percent of deadly and life-altering crashes on arterial streets in the city involved pedestrians.

A recent study found that among the nation’s 60 most dangerous corridors for pedestrians, almost all (97 percent) have three or more lanes, and 70 percent require people crossing the street on foot or bike to navigate five or more lanes. Compounding the risk, arterial streets are fast, often too fast for busy, urban areas. Three-quarters have speed limits of 30 mph or higher.

There is a reason these roads often resemble rural highways more than urban streets: about half of all urban arterial streets are owned by state highway agencies – not cities. Despite the fact that urban arterials often run through city centers and neighborhoods, states control the design, signalization, and speed limits on these corridors. And state DOTs, whose vast responsibilities range from rural roads to highway exchanges, often focus on fast vehicle movement through cities rather than safe, local access to schools, homes, and shops. Many state DOTs also often lack the resources to maintain their full urban networks, and few have the organizational setups or staff experience needed to design for the complexity and activity of urban streets where drivers, pedestrians, cyclists, children, skateboarders, scooter-riders, bus drivers, and taxi and delivery drivers all share space.

The extreme concentration of traffic fatalities and injuries on state-owned urban arterials makes fixing these roads an urgent task. Cities and advocates should push their states to transform arterial streets into safe spaces for all modes through the following key actions:

- Apply a context-sensitive speed limit-setting methodology. Speed is the primary factor determining whether someone will live or die in a traffic crash. Several states have recently passed legislation to grant cities more control over the speed limits on their streets, changes that have resulted or will result in speed limit reductions in places like Boston, Seattle, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

In addition to granting localities permission to lower default speed limits, states should evaluate and reduce speed limits on their most dangerous streets using the same context-sensitive approaches that the most safety-oriented cities are beginning to adopt. Many state (and city) agencies continue to rely on the 85th percentile approach, an outdated, unsafe method that allows a street’s fastest drivers to determine what the speed limit should be. Modern approaches to speed limit-setting, like NACTO’s peer-reviewed City Limits, provide a framework for proactively setting safe speed limits in urban areas by evaluating a street’s conflict density and activity level to determine the safest maximum speed.

- Adopt and apply design guidance that is appropriate for urban contexts. Arterials are designed to move lots of cars and trucks, fast. To design these streets, too many engineers take a page from the highway design guidebook – literally – and build streets with wide lanes and setbacks, long distances between crossing points, fast turns, and non-existent or insufficient space for people to safely walk, bike, or roll. But unlike highways, these streets slice through cities and neighborhoods filled with people walking, biking, and rolling and often feature significant commercial activity. The death toll on state-owned urban arterials demands swift changes in the design and management of these critical links in our transportation network. States must adopt guidance tailored to urban environments and apply engineering changes that are compatible with the multimodal needs of city streets. States like Massachusetts, Ohio, and Washington are leading the way by making real sidewalks and protected bike lanes standard features of the streets they design.

Changing the design of these streets will save lives. Contrast the fatality numbers on Roosevelt Boulevard or Hillsborough Avenue to those on the city-owned Queens Boulevard in New York City. Once known as New York’s “Boulevard of Death,” with 186 traffic fatalities since 1990, street design changes implemented over decades have dramatically cut fatalities and injuries and given the street a new reputation as a bike and pedestrian thoroughfare.

- Transfer ownership of state-owned roads in cities to cities. State agencies own over half of the urban arterials across the country.

For some states, it makes sense to transfer ownership of urban arterials to the cities they run through. Several states, including Texas and South Carolina, have launched initiatives to turn state-owned roads over to cities. These arrangements stand to benefit both the city and the state, offering the city more local control over urban transportation assets while allowing the state to offload an expensive piece of infrastructure to maintain. In San Antonio, the city took ownership over almost 22 miles of streets in exchange for much-needed enhancements on a few key corridors and with the promise that TxDOT would pay for all necessary one-time maintenance before handing them over. (Of course, this arrangement has become more complicated and politicized since). Such transfer agreements, when coupled with adequate financial incentives, can allow cities to make necessary safety changes to the streets known to be dangerous in their networks.

Arterial streets are the sites of recurring fatalities and serious injuries in nearly every city in the country. They must be fixed. Better safety outcomes hinge on adopting design standards and speed management practices that were developed for urban contexts, not primarily for highways. In many places, shifting ownership of the street is the best path to ensure that design and speed management changes happen quickly and thoughtfully. Together, cities and states, encouraged by partners and advocates, can reshape the arterial streets we inherited and make them fit for urban life.

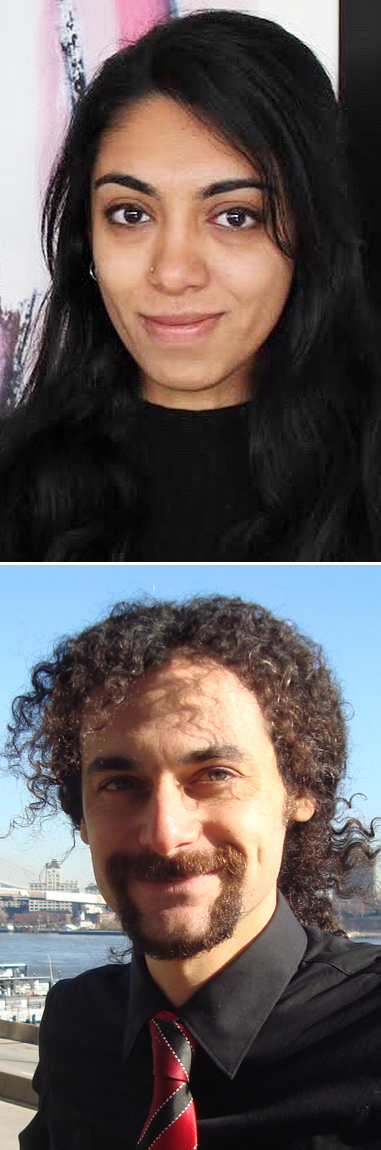

Sindhu Bharadwaj was NACTO’s program manager for policy until late 2022. In her role, Sindhu led NACTO’s engagement during the development of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and its subsequent implementation and worked to ensure cities had a stronger voice on the Hill and in the national discourse around transportation funding and policy. Matthew Roe is NACTO’s technical lead, with more than a decade of experience in planning and implementing great streets. He leads NACTO’s street design work in North America, serving as technical editor of the organization’s design guidance. Matthew has directly contributed to hundreds of miles of street redesign projects around the world — in addition to the streets designed thanks to NACTO’s street design guidance.