New Yorkers need some wins. We’re staring into an apocalyptic abyss, so we talk about change, but we know we’re not doing nearly enough. We have to be the change we’ve been waiting for.

There are many changes we need. One on which I work is reducing the dominance of King Car in New York City. Here’s an idea specific to reducing traffic.

Let’s start with what’s called “tactical urbanism.” Workers from the city Department of Transportation could put out Jersey barriers and rubber cones overnight and close the Brooklyn Bridge to cars and trucks in both directions. Tomorrow, the iconic span would be one of the most popular places in the city.

Almost nine million people visited the High Line last year. A car-free connection between Manhattan and Brooklyn would be even more popular. There are only three routes across the Hudson River for cars coming from New Jersey and points south and east, but the East and Harlem rivers have 18. Sixteen of them are free, and one of them, the Manhattan Bridge, is right next to the Brooklyn Bridge.

My office made some drawings for changing Brooklyn Bridge five years ago when I was working on a Lower Manhattan plan for the Financial District Neighborhood Association, on a team led by Buro Happold. A couple of years later, I wrote a Daily News op-ed with former Milwaukee Mayor John Norquist about closing the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. We wrote about reasons why New York needs to do more to reduce traffic.

What I want to focus on here is how much better we can make life in New York City after we reduce traffic. On the Brooklyn side of the Brooklyn Bridge, the elevated BQE and all the ramps and access roads built by Robert Moses to rush traffic between the highway and the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges created an urban wasteland in the historic center of what was once America’s second-largest city. Removing all the automobile-scaled engineering would create acres of empty and quiet city-owned land between Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO, and the currently auto-dominated park that stretches between Borough Hall and the Brooklyn Bridge.

One of the drawings my office made is a quick bird’s-eye sketch that suggests how a few simple changes could repair the torn urban fabric while creating sites for affordable housing and civic buildings. Cadman Plaza Park (let’s rename the expanded greenspace “Ruth Bader Ginsburg Park”) would become a green oasis and gateway for the bridge and Manhattan.

The number of New Yorkers using the bridge to commute back and forth every day would quadruple — not only because of the pleasure of standing and riding on the great bridge, but because people on foot and bikes take up so much less space per person than one or two people sitting in a car. I see this bridge from my office window; day and night, it’s choked with cars in stop-and-go traffic.

The bridge will serve more commuters while becoming an outdoor promenade. Overnight, the bridge will become quiet and pollution-free, blessed by harbor breezes.

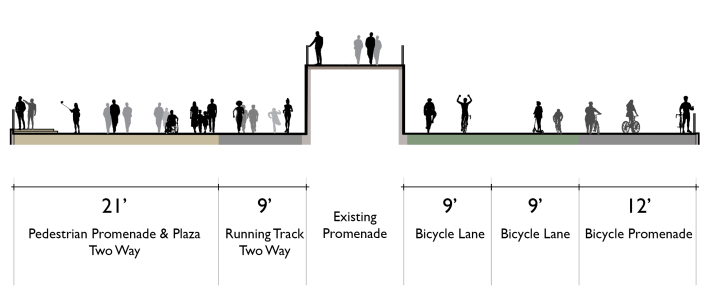

My office proposed reserving the north side of the bridge for cyclists. Today we would add electric scooters. It would be the greenest commute between Brooklyn and Manhattan (at least until its success led to the conversion of other interborough bridges).

The south side of the bridge, with stunning views of Lower Manhattan and New York harbor, would be for people on foot. The elevated walkway between the two sides of the bridge could be set up with food carts and seating. Some have proposed more activities and structures on the bridge, but the great bridge doesn’t need adornment. We proposed simple raised wooden decks between the beautiful stone piers.

The gateway would work in both directions, at both ends of the bridge. City Hall Park could be extended to the bridge. Walking from Borough Hall, through Ginsburg Park, and across the Brooklyn Bridge to City Hall and the Municipal Building would be one of the great urban experiences in the world. We wouldn’t have to do too much more than get rid of all the cars that now disfigure it.

I wrote a book called “Street Design, The Secret to Great Cities and Towns” with Miami urban designer Victor Dover. Syracuse recently hired Victor’s office, Dover, Kohl & Partners to plan for the removal of a downtown highway-in-a-trench, similar to a plan they’ve made for the removal of Interstate 980 in downtown Oakland.

Its Oakland watercolor shows a proposal to put Bay Area Rapid Transit tracks in the trench where the highway is now and then roof it over with a beautiful boulevard bordered by apartment buildings (see below):

The process is a bit like the cut-and-cover construction of the East and West Side IRT subway lines a hundred years ago in Manhattan and Brooklyn. Why can’t we do the same with the BQE viaduct in Cobble Hill and south? The discussion of where all that traffic would go is for another time, but no one who knows me will be surprised I have some ideas.

“My goal, my dream is to be like Amsterdam,” Sen. Chuck Schumer said recently. “I visited Amsterdam; bikes are way of life there. And it’s a beautiful way to live. New York has to aspire to that.” Then he announced he had secured “an effing lot of money” to make safer streets in New York City.

My colleague and op-ed co-author Norquist removed a highway spur from Milwaukee 20 years ago, spurring downtown development. Rochester removed a downtown highway a few years ago. If Milwaukee, Rochester, Oakland, and Syracuse can take highways out, we can, too. But our real North Star is in Europe. Their great cities already have more beautiful, safer streets than we have, while their residents generate a fifth or less of our carbon footprints per person.

We go to Europe to see great places. The walk or bike ride from Borough Hall to City Hall across an auto-free Brooklyn Bridge would equal any of them.