They're costs for concern.

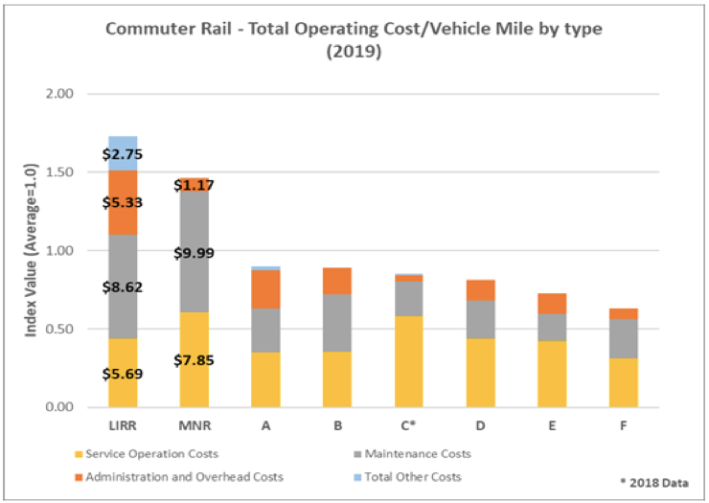

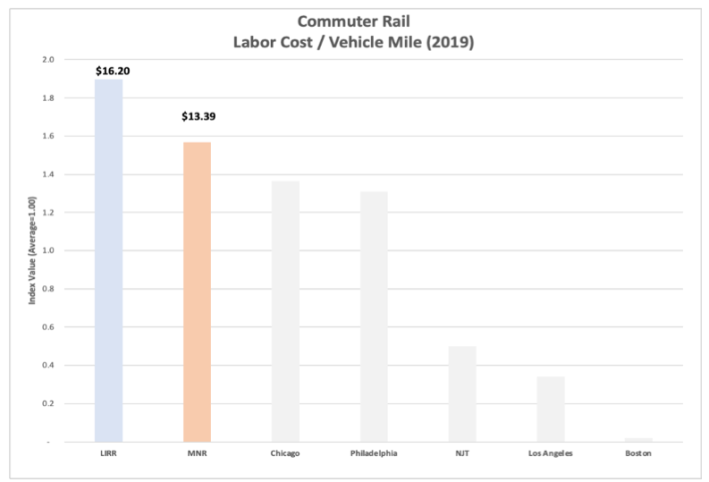

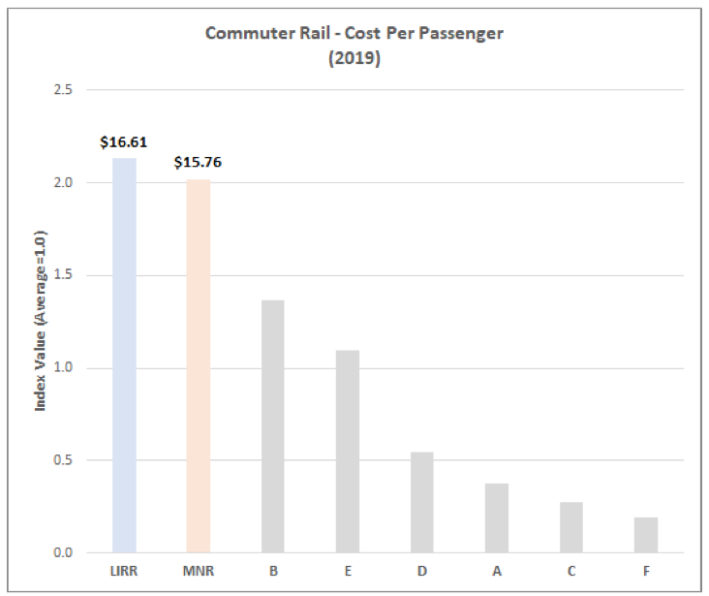

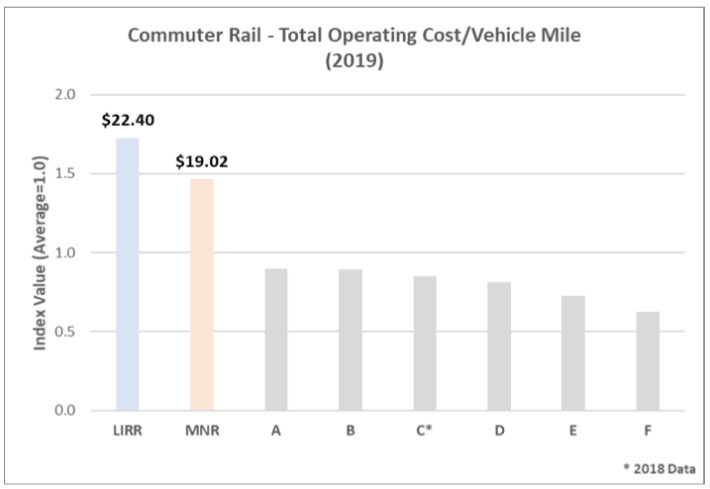

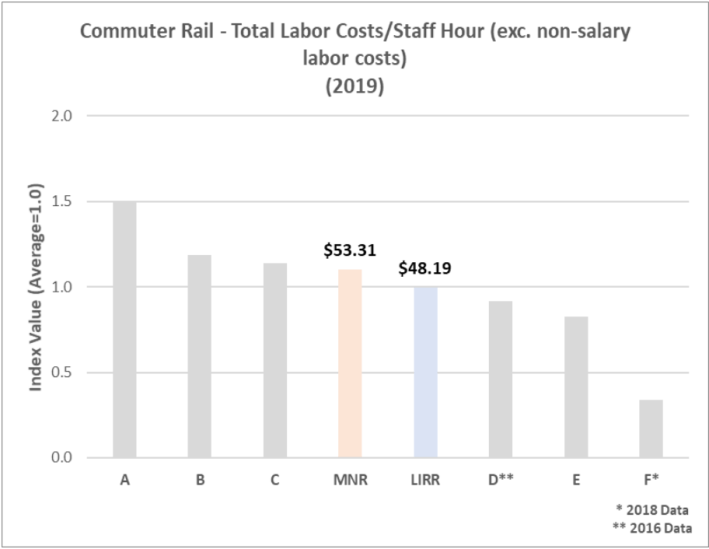

MTA efficiency does not stack up very well compared to cousin transit agencies around the country and the globe, according to the agency's first state-mandated performance report, a look at how much the MTA spends to run trains around our great metropolis and surrounding suburbs versus how it gets done everywhere else. Comparing New York to international cities, New York City Transit spends the most on labor, comes in near the top in areas like total costs per passenger and maintenance cost per mile. And on the heavy rail side, the MTA's commuter lines, the Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North, tower over the competition in terms of costs (one reason? MTA's commuter rail requires conductors to take tickets because its platforms are not controlled by fare boxes).

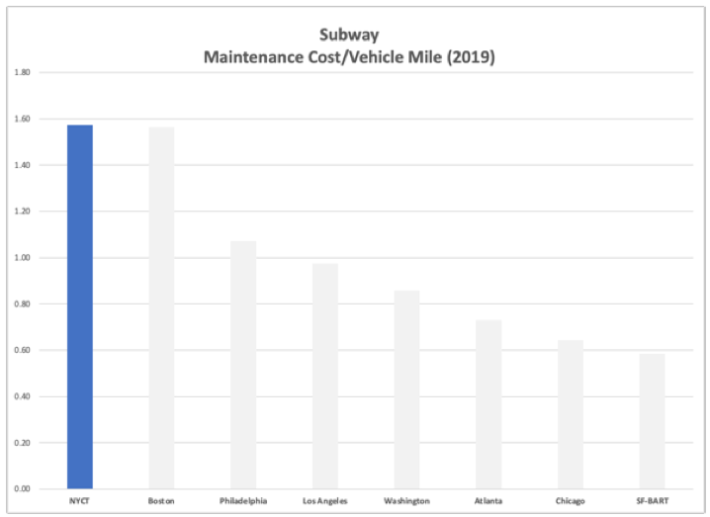

The MTA is famous (in a West Elm Caleb way) for its high construction costs, but the agency also has struggled to keep its operating costs down. The sprawling system is larger and has an older fleet than every transit system in America, which can help explain why NYCT's maintenance costs per vehicle mile are the highest in the country, while its overall operating costs per vehicle mile are third behind Los Angeles and Boston.

Internationally, NYCT is below average in terms of passenger trips per total staff and contractor hours, has the second-highest maintenance costs per car mile and the highest labor costs in the world. The LIRR also stands head and shoulders above international peers in terms of administrative costs, which the report says is due to the agency's pension contributions being classified as administrative costs, something international agencies and even Metro-North don't do.

For its part, the MTA said that it's learning and trying to change.

"A variety of factors drive MTA’s cost structure, including the age and size of the system, 24/7 operation, and the difficulty maintaining so many different — and older — models of train cars and other equipment," said MTA Communications Director Tim Minton. "Nevertheless, we have to make progress and are focused on specific opportunities for improvement, including addressing longstanding declines in employee availability rates and sharp increases in health-care costs and workers’ compensation claims and payouts."

Still, this kind of thing doesn't look great for our commuter-rail lines:

Nor does this...

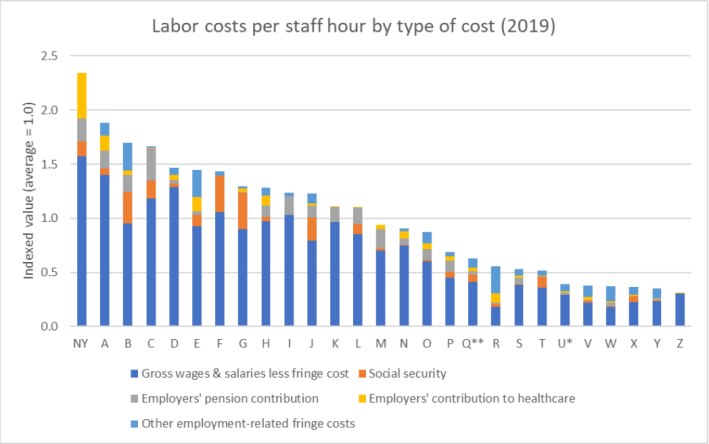

Nor does this...

Nor does this...

What else did we learn from the report? Here are the toplines (one caveat: the MTA's report did not name the 38 other international cities against which it was comparing itself because the international benchmarking organization, the Community of Metros, allows externally shared data to be anonymized):

Two people costs more than one

One Person Train Operation, otherwise known as OPTO, has been seen as the job-shedding white whale for MTA efficiency hawks for years. The concept, in which a train is operated by a single person instead of by driver and a conductor who controls the train doors, could save the MTA $221 million per year. Of course, it would also cost many jobs, making the proposal controversial in the eyes of transit unions, to say the least.

The MTA's internal view seeks to avoid a fight as well: The report noted that the agency's labor costs at NYCT are "above average" compared to other national transit services, but its authors said subway cars need two people for a reason that subway blogger Ben Kabak once called "New York exceptionalism at its finest."

"Given the significantly greater length of NYCT trains compared to most peer agencies, maintaining both the existing operator and conductor has been strongly and consistently advocated for by riders and elected officials," the MTA wrote in the report.

The line suggests the MTA is punting on the idea for the time being, but advocates for OPTO say that the MTA should consider the cost savings and get to it.

"The MTA really should be on a path to OPTO," said Citizens Budget Commission President Andrew Rein. "This would require fewer staff, would free up conductors to retrain as operators, and could thereby have mitigated some of the need for overtime and service reductions. They should be pursuing this now to help stabilize both service and costs in the future."

Thru-running can save money

Metro-North and the LIRR differ from other big cities because its trains stop dead in the central business district before turning around and heading back to the suburbs. In other places, those trains just keep going, picking up passengers as they make their way through big train hubs.

"[M]any international commuter rail systems feature through-running from one branch to another through their Central Business District, offering an efficient operating environment. In contrast, MNR and LIRR run terminal service operations into New York’s central business district, which requires making additional non-revenue train moves and drives up costs," the MTA wrote.

The transit agency and Amtrak have suggested that they can institute through running ... in 2080, after Penn Station is refurbished and the nearby Penn South annex is built, but advocates for making the change much faster noted that the agency has known about this problem and should do something about it before the end of the current century.

"In 2014, the MTA's Transportation Reinvention Commission released its final report, highlighting seven key strategies to help the agency plan, prepare for, and fund the next 100 years of transit investments," said Tri-State Transportation Campaign Policy and Communications Manager Liam Blank. "The Commission's recommendations called for increasing connectivity between the MTA and other regional transportation providers, implementing through-running service between MTA railroads and NJ Transit, and strengthening regional cooperation and integration. So this isn't news to them."

The tix fix

Speaking of things the MTA has known about for quite some time, the LIRR once tested out fare gates on its trains back in 1964, back when the idea of a Mets World Series was the height of comedy behind only The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Decades later, the LIRR and Metro-North still don't have fare gates or any other type of labor-free proof-of-payment system, which means when the MTA looks at efficiency issues, we get things like a chart that says, "If you take out the benefits paid to employees, these services are very efficient."

Axing over a thousand jobs is something the MTA would approach lightly, which is why the cost savings area of the report went hard on the commuter rail agencies' efforts to modernize their fleets and bring down maintenance costs. But budget-watchers say the small stuff can only go so far.

"This is really not a technical issue, it's politics and bargaining," said CBC Senior Research Associate Alex Armlovich. "The way this is written is consistent with the view that [the MTA] is going start with with low conflict stuff first."

The national failure of health care

The MTA, like all employers in these United States, bears the cost of its employees' health insurance (the yellow line in the chart above). Those yellow lines show up in other cities' overall labor costs — but you won't see similar yellow lines in the lines that represent European cities, or other cities in nations with national health-care coverage.

Freedom really isn't free — you're paying for it in health-care costs borne by employers.