A Brooklyn man was killed by a hit-and-run driver on a notoriously dangerous stretch of Atlantic Avenue in East New York on Friday night — a fatal crash that presents real-time evidence of the incompetence and apathy of city officials in keeping its most vulnerable residents safe.

Jose Ramos, 56, who was unable to hear, his family said, was walking home on Essex Street from a late shift at a store at around 10:10 p.m. when a white or light-colored sedan traveling westbound on Atlantic Avenue slammed into him, causing severe body trauma, cops said. Ramos's wife Martha, who is also deaf, told Streetsblog through her sister-in-law that Jose had called her from the store and asked her to join him so they could walk home together because Atlantic Avenue is so dangerous.

Martha said she and Jose, who was walking with his bicycle, stopped in the median of Atlantic at Essex Street, and waited for the light when the sedan "came out of nowhere" and slammed into Jose. The car, she said, was "racing" down Atlantic — an extremely common occurrence, she said.

"Everything happened so fast," Martha said.

Martha said she ran home, two blocks away, to get a family member to call an ambulance. When she returned to the crash site, the car was gone. EMTs took Ramos to Interfaith Medical Center, where he died.

Atlantic Avenue east of Pennsylvania Avenue is a speedway — and that is apparently how the Department of Transportation wants it.

The most-recent timeline of the agency's failure to control drivers in that area began in 2013, when then-Council Member Erik Martin Dilan, who was never a primary force for street safety, asked the agency to redesign Atlantic because of its race-like conditions. That request came shortly after the 2012 death of MTA bus driver James Neverson, who was killed nearby as he tried to cross another notorious strip, East New York Avenue.

Substantive changes were made to the western end of Atlantic Avenue around the same time, after Council Member Steve Levin shamed DOT in 2012 by bringing out a speed gun and reporting that 88 percent of the drivers between Hicks Street and Flatbush Avenue were going 10 or more miles per hour above the speed limit.

But the East New York stretch languished. In 2014, just after Mayor de Blasio took over, the city named Atlantic Avenue a "Vision Zero corridor." And Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams was optimistic, telling Streetsblog, "In 10 years time, we want to see a completely different Atlantic Avenue." At the time, city planners saw Atlantic as a true hub, thanks to nearby transit infrastructure. They promised "new public plazas," according to reporting at the time.

In December, 2015 — more than two years after Dilan raised the issue and well over a year after Atlantic was named a safety corridor — the DOT came to Community Board 5 with a proposal [PDF] so underwhelming, it is startling to think it even needed to be discussed with a community board.

At the time, the agency told board members that 52 people had been killed or seriously injured in more than 1,100 serious crashes on the 1.2-mile strip between Georgia Avenue and Logan Street between 2010 and 2014, placing it the top 10 percent of Brooklyn streets for severe injuries and fatalities per mile.

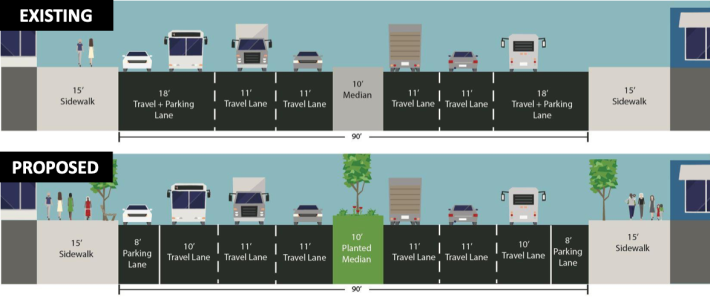

The agency's plan? Replace the three fast-moving, wide lanes with ... three fast-moving, wide lanes. Here is the picture that DOT actually presented to board members. Note the only change is a green median strip:

The road itself was not redesigned substantially, a violation of DOT's roadway reconstruction rules at the time, which stated that “excess width should be reallocated to provide walking, transit, and bicycling facilities, public open space, green cover, and/or stormwater source control measures.” (The PDF that contained that rule has been removed from the DOT website.)

Instead of narrower, or fewer, lanes to provide better walking or public open space, the DOT moved ahead with one part of its mission: stormwater control measures. The planted median that was, in fact, included in the project as flood control for the Long Island Rail Road tunnel beneath Atlantic Avenue. And in one way, it made the roadway safer for pedestrians, albeit in a manner that sought to make their lives more difficult so as not to inconvenience drivers: At the time, walkers frequently crossed the roadway by merely crossing the then-low median. The raised plantings eliminated their shortcut, as the photos below show:

The city's presentation also promised "high visibility crosswalks" and curb extensions to shorten crossing distances. The "high visibility crosswalks" amounted to a new coat of paint. And the curb extensions that were added to 15 locations removed a half of a parking space each; they did not reduce the width of the roadway or provide any traffic calming, as the photo below shows:

In fact, the project seemed entirely focused on making sure drivers are not delayed in the high-speed corridor between Eastern Parkway and Conduit Avenue; in its presentation, the DOT said that there were "design constraints" because of "heavy traffic volume" in the area that reduced the agency's ability to make the roadway truly safe. The goal, the agency admitted, was to create a "more comfortable driving experience" that included left-turn bays so that drivers were not stuck behind other drivers.

As Streetsblog reported at the time, "The design proposed by DOT will make Atlantic look nicer ... but it does not fundamentally alter the geometry of the street." (Later, Transportation Alternatives singled it out as insufficient, on the grounds that "these interventions are designed to protect pedestrians from dangerous drivers, instead of implementing changes that would fundamentally alter dangerous driving behavior, such as ... decreased traffic lane width and other complete street innovations.")

Crucially, the city's timeline for the project has been epically slow. Though it was presented to the community board in mid-2015, work did not begin until late 2018, according to archival photos. The $48-million project was completed in mid-2020, and a city press release praised the effort to make Atlantic Avenue more "welcoming." It is certainly that. But is it safer?

In 2017, the last full year before the renovations, there were 561 reported crashes in the 1.2-mile strip, injuring 154 people: six cyclists, 26 pedestrians and 122 motorists. So far in 2021, 124 people have been injured on that stretch of roadway — on pace for 159 injuries, or roughly the same number that the roadway experienced before renovations were made.

The project between Georgia Avenue and Logan Street was designated merely as Phase I of the so-called "Great Streets" project for Atlantic Avenue. Phase II of the project, between Logan Street and Rockaway Boulevard, was almost mentioned along with Phase I back in 2015, but it was not presented to the community board until early 2018 [PDF] — too late to save the life of Rodney Graham, a pedestrian struck on that stretch in early 2016. Under the revised timeline, construction was supposed begin in 2019.

It never happened.

Now the project does not appear to even have funding. According to the DOT's dashboard for the project, $33 million had been lined up in 2016 to pay for the raised, planted median, additional cement for curb and median extensions, street trees ("where feasible"), public art, wayfinding signage and CityBenches." At that time, the project was supposed to be completed by May, 2020.

In May 2019, the budget had mysteriously grown to $42 million, and the completion date had been pushed back until December, 2021.

By October, 2020, the project's budget had increased to $44 million, and the completion date pushed back to December, 2022.

Now the project does not have a budget or a completion date, according to the dashboard. Advocates also noticed that this week:

Once again, @NYC_DOT’s ignoring Atlantic Ave, the only @NYCMayor #VisionZero “Great Streets” to not be fixed: After putting off needed #bikenyc/#walknyc-friendly project for *years*, there’s now no completion date to #fixAtlantic at all!

— DHFixAtlantic (@DHFixAtlantic) October 15, 2021

Where’s *our* Great Street DOT? https://t.co/jxmkpxZyBG pic.twitter.com/W7o8D9Ppll

But delays and lack of concern are common in the poorer corridors of this city, where existence is barely eked out and the wealthy tend to only notice as they speed past on their way to JFK. Atlantic Avenue, Pitkin Avenue, Pennsylvania Avenue, New York Avenue — these remain dangerous speedways with conditions that are simply not improved year after year.

And now Jose Ramos is dead.

"A nicer guy, you'd never meet," said his landlord, Lilly Rivers. "He was one of the best. Anything he could do for you, he would do for you. It's a terrible thing that he is dead."

Rivers told Streetsblog that she never goes to Atlantic Avenue even though it is just two blocks from her home.

"Drivers are crazy over there," she said. "That's why I don't go."