The easiest thing in the world is taking a train from Midtown Manhattan to America’s newest, and possibly most glorious, national park. The hardest thing in the world is getting from the train station in the center of the New River Gorge National Park to a hotel room or rental car.

And that, in a nutshell, is the problem for the brand new national park, which reached the elite status only in January of this year. Amtrak offers thrice-weekly direct service from Moynihan Hall to three stations inside the park — yet none of the depots offer services that are needed if the New River is indeed to become one of the top, environmentally friendly world destinations.

I am trying to change that.

But enough (for now) about me. This is the story of a stunningly beautiful, deeply historical, and long-exploited region that is poised to capitalize on sustainable tourism in an age when vacationing itself is fraught, thanks to the carbon footprint of all those cars and your planes. It’s sort of ironic that this corner of West Virginia is so well suited: for decades it was chewed up by the coal and rail industries. But now that they are finished exploiting the region, it has rebounded into a paradise — one accessible by direct train from Moynihan Hall in 12 hours.

The problem is, the new national park isn’t ready for you yet.

First, why you must visit

When you tell your fellow New Yorkers that you are headed to West Virginia on vacation, almost all will say, “Why?”

They say that because simply don’t know what they are talking about. And let’s let them keep thinking that way because we don’t need them ruining John Denver’s famous “almost heaven.”

Whitewater rafting enthusiasts have flocked to the gorge since the late 1960s, when commercial rafting companies started operating in a region only a few years removed from the last coal mining exploitation in the region (of course, other parts of West Virginia are still being decimated by coal extraction, which employs almost no one, yet still dominates the political landscape of the Mountain State). By the 1970s, the gorge was declared a “national river,” and more tourists came, still drawn by the championship-grade rapids of the Gauley River and the less-intense, but still heart-pounding current of the New River (which, despite its name, is one of the oldest rivers in the world).

The gorge created by New River as it makes its weird path from western North Carolina to Gauley Bridge, is a Grand Canyon of the East, albeit covered in lush greenery that reclaimed an area once fully denuded by coal companies. The rafting is still top notch, but now tourists flock for the hundreds of miles of hikes along the river, on top of the gorge and from the canyon rim down to ghost coal towns, some of which still have historic structures such as coal conveyors, mine shafts and rail sidings. Plus the region remains interesting to the history buff: it is a crucible of the American labor movement, and a reminder of the role Wall Street played a century ago in internally colonizing West Virginia (once reliably blue, now as deep red as anywhere in the nation). You could spend a week in this national park and only explore the union history, which was born in the dust of the mines and the heat of the coke ovens that still pockmark the gorge.

The saga begins

To get to the New River Gorge National Park without a car, you’ll need the Amtrak Cardinal, which, unfortunately is the red-headed stepchild of our already beleaguered national rail network. Three times per week, it cuts a bizarre arc between New York and Chicago:

It’s important to note that one of the reasons the Cardinal even exists is because freight rail was so crucial to the region’s initial exploitation — rails and coal mines financed by Wall Street sucked all the riches out of West Virginia, and when the riches were gone, investors sucked elsewhere. But the tracks remained, still hauling freight, but also offering a new way of thinking about tourism in America: the new freight is passengers.

The Cardinal costs just $82-$108 each way (group discounts apply, too), but the price alone is not going to make many converts out of Americans, who typically equate tourism with the words “road trip!” And here’s why:

The train leaves Moynihan station at 6:45 a.m. (an hour made all-the-more ungodly by the fact that there’s nowhere to sit at the Moynihan Train Hall) and arrives at Hinton (the first stop inside the national park) at 6:06 p.m.; at Prince at 6:43 p.m. and at Thurmond at 6:58 p.m.

Now, you can spend days poring over the Amtrak Cardinal schedule (we did), but you won’t be able to make the math work because, basically, after 6 p.m., West Virginia shuts down. Indeed, the only amenity at the depots in Prince or Thurmond is the sign with the town’s name next to the railroad tracks.

By the time the Cardinal pulls into Prince or Thurmond, the rental car office in the nearest town (Beckley) is closed. The closest taxi service charges $50 to pick you up. That just wasn’t going to do, so I called the mayors of Prince (pop. 93), Thurmond (pop. 6) and neighboring Beckley (pop. 16,452) to find out whether any of them was working on a plan to connect car-free New York tourists to lodging or rental cars — or otherwise promote what some of us (well, for now, me and my girlfriend) believe is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity thanks to the new national park designation.

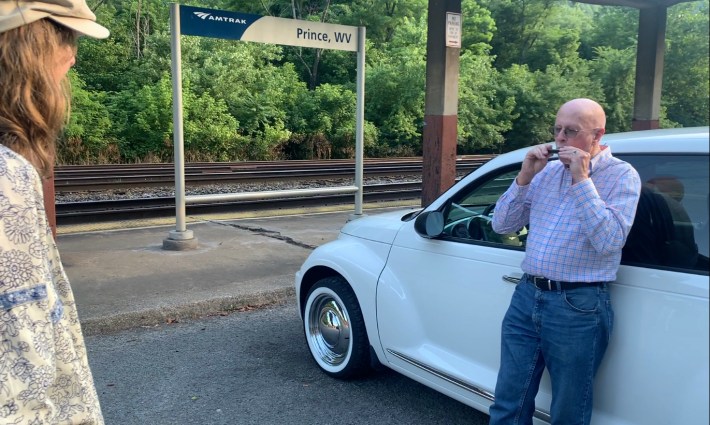

None of those cities had a plan, but all of the mayors did promise to pick me up personally (which is not really sustainable if thousands of New Yorkers start showing up in the national park three days a week on the Cardinal). The mayor of Beckley, Robert Rappold, hooked me up with rail enthusiast David Gay, who picked up me and my girlfriend in his 2000 Chrysler PT Cruiser, which looked like the day it came off the car lot — a gorgeous vehicle, but, again, not really a good plan for tourist hordes. (We ended up taking Gay to dinner at Pasquale’s and a subsequent Lady D concert at the Freefolk Brewery in nearby Fayetteville, so it all evened out.)

The other gorge-zone city with an Amtrak stop is Hinton, which is poised to be the southern gateway to the entire region. “Poised” is the operative word. Thanks to the decade-long efforts of a local millionaire (more on him later), there is a seven-room B&B within walking distance of the train, but no rental car agency. (Hinton’s nice, but not that nice. This is one of the few times Streetsblog will ever publish this sentence: You need a car for this trip because the many attractions of the gorge are inaccessible otherwise.)

Hinton Mayor Jack Scott spoke to me at length over two conversations (one held uncomfortably next to the town’s Confederate memorial). Like me, he is convinced that Hinton will be the park’s boom town, thanks to its location at the convergence of three rivers, near two state parks in addition to the national park, near the picturesque Sandstone Falls (itself a destination), and with a dam that creates a large lake for recreational boating and fishing. It is not hard to imagine tourists using Hinton as a base, but it is hard to realize: twin, decades-long crises — the collapse of the local economy and the rise of opioids — have left Hinton a shell of its former self as a prosperous coal center. Right now, one third of Hinton consists of well-maintained homes and historic businesses, one-third run-down homes that are barely holding on, and one-third homes that are simply abandoned. But therein lies the possibility, too.

“I feel confident you will see dramatic change in the next 12 months,” Scott told me. “Hinton is going to be a player in all of this!” But he also admitted that one challenge is getting Amtrak to promote the Cardinal to New Yorkers (and would-be tourists from Chicago, too) and then making sure there are services for them when they arrive. When I reminded him that there’s no way for people to get around once the Cardinal drops them in Hinton, he cheerfully said, “You’ve got a great point there, buddy.” (I also reminded him that the Confederate monument is a monument to hate and insurrection that must be removed. He was less concerned about that than he should be.)

Amtrak: part of the solution?

One challenge is Amtrak itself. The rail system barely promotes its Cardinal line, which is the only train east of the Rocky Mountains with direct service to a national park from New York, Washington and Chicago.

Everyone wants to paper over that lack of promotion. When I asked about it, several people inside and outside the company sent me a link to the “Amtrak and America’s National Parks” page on the rail system’s website, but that page not only does not have a link to the Cardinal web page or the New River Gorge National Park, but the only two national sites it lists — Glacier National Park and the historic site at Harpers Ferry — have links to dead web pages. (When I first asked Amtrak to comment for this story, a representative of the rail system merely sent over a fact sheet about the Cardinal — and a link to that very same national park web page … with those very same dead links.)

Fortunately, Amtrak Vice President of Long Distance Services Larry Chestler saw the importance and the possibility of Cardinal-to-Park transportation and agreed to speak to me. What he said, however, was not that optimistic:

“We have not done anything specifically to raise awareness of the new park, and it remains an opportunity,” he said, shifting the conversation to the relaunch and modernization of the rail network’s popular $499 USA Rail Pass.

He also touted Amtrak Vacations, which feature packages put together by third-party tourism companies. Currently, no such packages are offered in the New River Gorge National Park, though.

Chestler sense my pessimism that Amtrak could play a leadership role in getting hundreds of people to the park in one train rather than in scores of cars.

“Your point is valid about the role we play in promoting specific destinations,” he said. “I don’t know that we’ve had a discussion with [Amtrak Vacations] about the New River Gorge. The truth is, there is limited [tourism] infrastructure there and we don’t have the wherewithal to create it. Maybe part of the value of your story is helping people to understand what is needed.”

The situation leaves locals frustrated.

“I’m not aware of any effort by Amtrak,” said Ken Allman, the aforementioned local hero who made his fortune in medical software, and has been buying up properties, renovating the local depot, planning a hotel, opening a popular restaurant and theater and generally serving as the town’s biggest booster. “It’s like something out of a reality show that all of a sudden the world might want to come to our town after so long. But we need Amtrak to be receptive to supporting us. The Cardinal has been the stepchild of Amtrak. But there is a greater reason to use the Cardinal than ever, thanks to the park.”

According to the National Park Service, visits to the New River Gorge have increased 24 percent since the park was designated on Jan. 20, 2021. But Amtrak’s numbers do not show a similar increase; people are visiting this park in droves, but they’re not doing it by rail.

West Virginia Director of Tourism Chelsea Ruby admitted she was most focused on getting people to her state via car or plane, which doesn’t do anything but add a lot of pollution to a warming planet.

“We could not be more excited about the new national park designation,” she told me. “Time magazine just called the gorge one of the world’s greatest places.”

But for now, Ruby said the state’s efforts were limited to helping tourists make itineraries once they get to the region.

“Most people will drive or fly,” she said. “But we will be looking into a rail strategy.”

The answer: David Gay

Anyone who starts making calls to random mayors as part of his planning process for visiting the New River Gorge National Park by train eventually ends up talking to the aforementioned retired pharmacist with the pristine PT Cruiser, David Gay.

When I finally got him on the phone to discuss my trip from Penn Station to Prince station, he spoke rapturously.

“So you are going to come to the New River Gorge by rail — as God intended it!” he said.

He was, of course, well versed in every single scenario that my girlfriend and I had tried to map out: getting to the park is easy; getting away from the Prince station is impossible. Many of the area cities — Fayetteville on the north, Beckley on the west, Hinton on the south — have bus service, but none of those transit systems connect to each other at Prince, which would be a logical place (at least on the days when the train comes in).

Gay’s mission for now is convincing local authorities to act because the Cardinal has the potential to transport thousands of New Yorkers to the gorge region — and the region stands to profit mightily from the influx.

“Tell everyone in New York: Imagine being able to ride from Penn Station, as God intended it, to a national park! How do you think the people of New York would like that?”

First, Gay wants the Cardinal to operate daily, which is logistical challenge because Amtrak operates on tracks owned by CSX, a huge freight operation that is interested in making money for shareholders, not memories for tourists. How could that situation be changed? As the Rutles sang, “All You Need is Cash.”

Daily Cardinal service (which existed until 1981, and has long been sought by West Virginia politicians including Sen. Joe Manchin) would not be difficult, Chestler said, if Congress would cough up more resources so Amtrak could get more access to the busy CSX freight lines through the gorge. (Neither Manchin nor the Mountain State’s junior senator Shelley Moore Capito returned our calls.)

Second, there’s the logistical challenges for tourists upon arrival.

Allman is the one person who stands athwart hope and history. Several people I spoke with in the region said he has the capital and the vision to seize on the region’s inevitable boom. He’s operated a small hotel since 2007, but delayed his own plans for a bigger lodge at the train station itself because “it didn’t look promising.”

But that was before the national park designation.

“The world is coming to Hinton and we’re not ready,” he admitted. “Now you have to give us two years.”

He expressed disappointment that when Outside Magazine recently did its own guide to the gorge region, it focused mainly on Fayetteville, the “Coolest Small Town” at the park’s northern end that has been serving whitewater tourists for decades and is mostly fully built out as a tourist destination (the article also did not mention listing the park via Amtrak, another oversight).

But Allman is hopeful because local, state and federal officials are finally all on the same page.

“That’s huge,” he said. “Everyone is listening. Nobody really saw a path forward until now.”

If you go

We don’t do a lot of service journalism at Streetsblog, but if you’ve come this far in the story, maybe you’re actually thinking of visiting the region. It’s impossible to list all its attractions, but here are a few:

Hiking

There are so many historic or merely picturesque hikes in the park and on its fringes. Here were my favorites:

- Nuttallburg Coal Tipple hike: probably the best preserved remnants of the region’s coal exploitation past.

- Long Point: An easy hike, but the best view of the gorge and the great bridge.

- Endless Wall Trail: the best view of the gorge without the bridge.

- Kaymoor Mine hike: You’ll need to prepare yourself for 826 steps, but this hike offers lots of coal history.

- Old Ferry Road hike: For a view of the Gauley River, where Confederate General John B. Floyd and his troops fled after the Battle of Carnifex Farm.

Rafting

Whitewater rafting on the New and Gauley rivers offers excitement at all levels. The Upper New (confusingly the southern part of the river) offers gentle rafting. The Lower New is exciting but not death-defying. The Gauley — especially during the October season when water is released from a nearby dam — features world-class level rapids.

- Adventures on the Gorge

- New and Gauley River Adventures

- ACE Rafting

- Cantrell Rafting: Operates on the calmer Upper New — perfect for families.

Historic sites:

- Carnifex Battlefield: a fairly crucial early Civil War battle.

- Beckley Coal Mine Museum

- Historic grist mill: The still-working mill on Glade Creek in Babcock State Park dates to the 18th century.

Biking

- Greenbrier River Trail

- Arrowhead Bike Farm: mountain-biking trails, goats, camping and a beer garden.

Other recreation

- Summersville Lake: Formed by a Johnson-era dam on the Gauley.

- Bluestone State Park: Featuring Bluestone Lake, formed by a dam on the New River near Hinton.

- Bluestone National Scenic River: Lives up to its name.

- Pipestem Resort State Park: A family resort park with ziplines, but also hiking.

- Sandstone Falls: The biggest falls on the river. Just north of Hinton.

Other

- Bridge Day, Oct. 21, 2021 (third Saturday of the year): The New River Gorge Bridge — the highest arc bridge in the Western Hemisphere — is closed for a full day of activities including BASE jumping.

- Autumn Colors Express (also Oct. 21): a full-day rail ride between Huntington and Hinton to look at the leaves.

- Bridge Walk: Walk in the undergirding of the gorge bridge for a once-in-a-lifetime view (and engineering lesson).

- Ritz Theater: First run movies in Hinton.

Eating

- Freefolk Brewery: The aforementioned brewery offers great food (try the potato nachos) and a stage with regular local musical performances.

- Pies and Pints: The flagship of a growing southern pizza chain with surprisingly good pies.

- The Pink Pig: A new BBQ joint in the heart of Fayetteville.

- The Market on Courthouse Square: Great sandwiches and burgers in Hinton.

Gersh Kuntzman is editor of Streetsblog. He is also a huge booster of the New River Gorge region. If you have any questions for him, he would likely answer them. Email him here.