A classic piece of British folklore about cities is the story of "Dick Whittington and his Cat" — a tale, with roots stretching back to the 14th century, about a young man who travels to London because he's heard that the streets are paved with gold. Finding a cruel reality of poverty and grime, he learns from his illusions, becoming the mayor of London and improving the lives of the people.

The idea behind the story sets the scene for a new campaign linking New York, Paris and London. Car Free Megacities seeks to leverage the huge opportunities to build back better from the coronavirus pandemic and improve our health and quality of life. Like young Whittington, residents of the three metropolises face streets not paved with gold, but rather clogged with traffic and full of air pollution that smarts our eyes, weakens our immune systems and shortens lives. As in the tale of Whittington and his cat, we hope that mayors can help bring about a turn in our collective fortunes.

Car Free Megacities's dashboard shows the striking similarities and also the differences between London, Paris and New York — the metrics the cities can use to learn rapidly from each other and take actions that will save lives, make streets healthier, pleasanter places and deliver critical progress toward urgent climate goals.

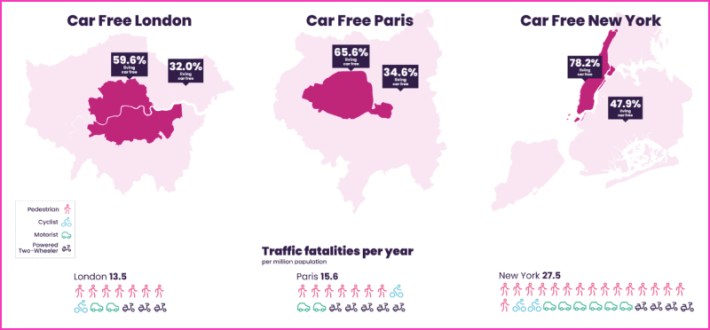

The cities have fairly similar populations — ranging from seven to nine million. Even as each has seemingly endlessly congested roads, large numbers of people based in each inner city areas already live car free. Six out of 10 people live without cars in London, slightly more in Paris and almost eight out of 10 in New York. Unfortunately, the fact that many New York households lack cars hasn’t yet made its streets safer than those of Paris and London — pointing to one area that could see dramatic improvement. New York saw at least 243 killed in traffic in 2020, compared with 110 in Paris and 121 in London.

Meanwhile, Paris, despite its romantic reputation, scores worst among the three in air pollution, as measured by nitrogen dioxide and small-particulate matter. London and New York have similar, bad air-pollution problems; both routinely breaking World Health Organization guidelines. London, for example, overshoots the air-pollution limits set for a whole year by the first week of January.

Parisians could spend their time in many better ways than being stuck behind the wheel of a car, but drivers there lose the most time in traffic, with London second and New York third. Even so, Paris has the largest proportion of trips made by foot — fully half — compared with just one in four in London and just under one in three in New York.

Even as the pandemic lockdowns have underscored the importance of making more space for people on city streets, cars hog huge amounts of space in all three cities, around 11.5 square miles or more, the equivalent of around 4,200 soccer fields. A glimpse of better potential city living at the height of lockdowns when traffic reduced dramatically, came from how nature crept back into our lives, with more people taking advantage of green spaces, and with nature making itself more heard with birdsong.

London, New York and Paris have something else in common: in all three, residents resisted traffic-reduction measures that ultimately proves popular once people experienced their benefits. In London, it was congestion pricing; in New York, pedestrian plazas; in Paris, "Respire" zones, a car-free scheme in which certain districts are closed to motorized traffic on Sundays and public holidays. The campaign hopes to leapfrog and fast track measures for traffic reduction, by demonstrating that common, shared fears about them typically evaporate with familiarity. Our research shows that this has been the case internationally for decades.

Paris, London and New York in the leading peloton of the greenest cities where cars would become the fifth wheel of the coach? Yesiiii 😃!

— Gaudinot Élisabeth (@GaudinotE_green) March 4, 2021

The "Car-Free Megacities" project starts today 🚲!

FB➡️https: //t.co/EWgWDtNwGr

Registrations➡️https: //t.co/yWZaaaBq5v https://t.co/FGaqci4N0A

A "car free city" is not a city with no cars. Some people, including those providing essential services or with disabilities, will require use of a car. But reducing the overall number of private cars in megacities will make living easier.

In the British story, "Mayor" Dick Whittington turned around his fortunes and London's. Car Free Megacities exhorts the mayors of Paris, New York and London to learn from the pandemic, and from each other, and work together to make their cities more livable. It’s not about paving streets with gold, but rather about cleaner air and allowing more space for people and nature.

To learn more about the Car Free Megacities campaign, visit https://www.

Andrew Simms (@AndrewSimms_uk) is co-director of the New Weather Institute, coordinator of the Rapid Transition Alliance and co-author of the original Green New Deal. Hirra Khan Adeogun (@hirr4) is the overall coordinator and campaign lead of the Car Free Megacities. Car Free Megacities is a collaboration of climate charity Possible, the New Weather Institute, Paris sans Voiture, Brooklyn Spoke, Westminster University’s Active Travel Academy and Glimpse, supported by the KR Foundation, and Brompton.