Analysis: Yes, MTA Should Shut Lines — But Not the Whole Subway! — for Repairs

12:01 AM EST on February 4, 2021

Metropolitan Transportation Authority officials offered yet another rationale for their overnight subway closures last week, saying that barring patrons between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. has allowed workers to accelerate much-needed repairs — but all that does is raise questions about how the MTA does its work in the first place.

“We’ve gotten a ton of extra work done,” Janno Lieber, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s chief development officer, said last week, calling those accomplishments “a huge benefit to the system.”

The closures — which began on May 6, 2020, ostensibly for the purpose of disinfecting trains and evicting the homeless — have saved the 2,000 to 3,000 workdays on a range of projects, even as the authority continues to run empty trains throughout the system during the overnight hours, Lieber and other officials told a state legislature budget hearing on Jan. 26.

Let’s stipulate that the shutdown has actually been a boon for projects. But are the closures — the first such nightly cessation of service in the system's 107-year history — the best way to accomplish the work? As subway ridership remains low — it’s still 70 percent below the pre-pandemic figure of 5.5 million passengers daily — some analysts and advocates think the the MTA could do better by restoring full 24-hour service, but entirely shutting down lines that need repair to finish work quickly and efficiently while inconveniencing fewer people.

That's especially true as a host of lawmakers — including several who questioned the MTA officials at the hearing — have expressed the concern that the closures unfairly burden communities of color and essential workers, who must make extraordinary, time-consuming arrangements in order to get to overnight jobs. According to TransitCenter, an advocacy group, census figures show that the vast majority of those workers — 69 percent — are Black or Hispanic, and about a third are low income.

"Gov. Cuomo’s decision to shut down the system each night has stranded tens of thousands of New Yorkers who depend on the subway to access overnight shifts at hospitals, airports, pharmacies, and bodegas," said Colin Wright, TransitCenter's senior advocacy associate. "Targeted line closures with replacement bus service can improve track access and construction efficiency without the severe, inequitable impacts of a systemwide shutdown. Cuomo and the MTA can help New Yorkers get to work by balancing the need to keep the subway safe with the need to keep the system running."

Others saw a bit of flim-flam behind the MTA's boasts.

“The MTA is searching for an ex-post-facto rationale to explain why they have denied so many essential workers access to the subway for the duration of the pandemic,” said transit expert Ben Kabak, who blogs at Second Avenue Sagas. “The trains are still running, and if work productivity has become one of their chief concerns, there are better ways to tackle that problem, including shutting down single lines and providing adequate replacement bus service. Simply put, the MTA system is too vast and the list of pending projects too large for all work to happen at once in four-hour windows overnight, and the MTA knows how to improve worker productivity if that is a driving concern."

The idea that subway work is best accomplished by extended closures on parts of lines is hardly controversial. The august Regional Plan Association proposed a more-efficient approach to repairs in its “Save Our Subways” report several years ago.

“Providing longer work windows is essential to completing work faster and more cost-effectively ... by closing lines entirely for a shorter duration, such as the planned 15-month suspension of L train service to repair damaged tunnels,” the report said, referring to a plan that never happened because Gov. Cuomo intervened. “The MTA should prioritize lines that have a critical mass of issues that affect capacity, and they should provide robust alternative surface transit service options during the closures.”

The closures must be accompanied by “frequent high-speed bus service,” which would “even provide superior service for most riders given that late-night service subway service is already infrequent and unreliable, and that buses could run frequently on largely uncongested streets overnight.”

Of course, providing fast routes for MTA buses would be the job of the city Department of Transportation — which has moved slowly on busways.

In order to compensate for crucial subway work, the MTA should be “running priority bus lanes on Queens Boulevard, Lexington Avenue, and Eighth Avenue,” said Danny Pearlstein, the director of communications and policy of Riders Alliance, although he acknowledged the sticking point that such bus lanes would “require coordination with the DOT” and likely “three years of public meetings.”

The question of what the MTA could be doing differently or better is worth asking as the prolonged closures engender controversy among lawmakers, transit advocates and the public — and as the MTA suspends the bulk of its $51-million capital plan because of its dire financial situation, curtailing all but current projects.

Many have questioned whether the closures really are for the purpose of disinfecting the system, calling the cleanings so much “hygiene theater.”

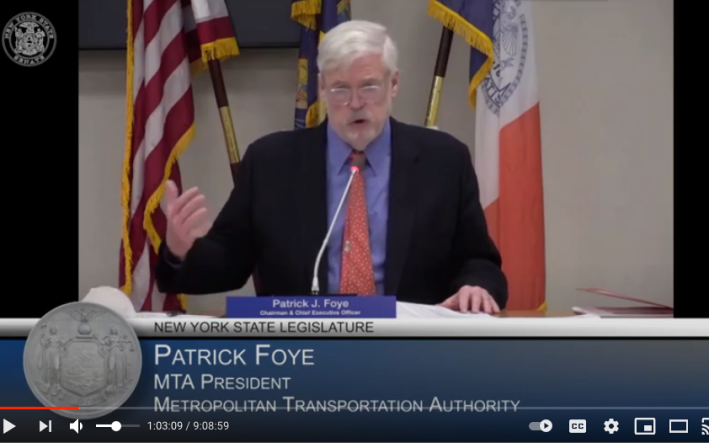

At the hearing, MTA President Patrick Foye defended the closures as a pandemic necessity even as several lawmakers described the hardships the lack of overnight subway service visited on their constituents.

“When [Gov. Cuomo] declares the happy day that the pandemic is over, we will begin to move to restore” 24/7 service, Foye told the hearing — although he couldn't produce any data buttressing his disinfection claims, even in the teeth of extended questioning from lawmakers.

Researchers have shown that transit is not a vector of coronavirus spread. A study conducted by the American Public Transportation Association and looking specifically at New York City found no direct link between the subway and COVID-19 infection rates.

Others have charged that the closures are really for the purpose of ridding the system of the many homeless New Yorkers who live in it. As the Daily News noted last week, “Gov. Cuomo ordered the subway shutdown after reporting from the Daily News revealed homeless New Yorkers were using the system for shelter during the pandemic, calling the conditions ‘disgusting.’”

Meanwhile, MTA officials acknowledged at the hearing that the closures haven’t saved the authority a dime.

“That was not done as a cost-saving effort,” MTA Chief Financial Officer Bob Foran told the lawmakers. “We are still running trains to get our workforce back and forth and we are running buses to help our passengers and our customers to move.”

So what's the point?

“The MTA stands for ‘Money Thrown Away’ during the overnight shutdown of the city’s subways,” as the Daily News put it last week.

And the city and its workforce suffers.

“At this point, the sanitation theater is about assuaging a nervous public and removing homeless New Yorkers from trains,” Kabak said. “Neither of these are worth the cost of denying so many people powering the city a fast and convenient subway ride each night, especially considering the trains are still running.”

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog New York City

Friday’s Headlines: Canal Street Follies Edition

Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine isn't happy. Plus otherness.

Daylight Again: Bronx Community Board Backs Parking Ban at Intersections

The Boogie Down is down with daylighting!

Community Board Wants Protected Bike Lane on Empire Blvd.

Brooklyn Community Board 9 wants city to upgrade Empire Boulevard's frequently blocked bike lane, which serves as a gateway to Prospect Park.

The Brake: Why We Can’t End Violence on Transit With More Police

Are more cops the answer to violence against transit workers, or is it only driving societal tensions that make attacks more frequent?

Report: Road Violence Hits Record in First Quarter of 2024

Sixty people died in the first three months of the year, 50 percent more than the first quarter of 2018, which was the safest opening three months of any Vision Zero year.