The city has finally broken ground on a 15-year-old plan to protect cyclists and pedestrians along a stretch of scary roadway in Sunset Park — but the plan falls short of what most commuting and working cyclists need, and doesn't fix the most dangerous part of the neighborhood, elected officials and advocates say.

Way back in 2005 — yes, when George W. Bush was still the president — the federal government allocated $14.6 million to build the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway. Fifteen years later, large swaths of the safe route have yet to be built, and the protected pathway planned for the upper part of Third Avenue in Sunset Park stops short of the roadway's more deadly sections, leaving pedestrians and cyclists, especially delivery workers, as vulnerable as ever.

“How many more people have to die before action is taken on Third Avenue?” César Zúñiga, the chairman of Community Board 7, said during a vigil earlier this month for the latest victim of Third Avenue — 31-year-old Clara Kang, who was killed near 55th Street on Oct. 3 by a motorcyclist after finishing her nursing shift at NYU Langone Hospital–Brooklyn. “I’m going to continue to ask in my role as chair to ask all our elected officials and agencies to step up and do something about something so basic as pedestrian safety and traffic calming.”

Today we mourn the loss of #CarlaKang. How many more have to die before @NYC_DOT and @NYCMayor take action to make 3rd Ave safe for pedestrians and cyclists? The #solutions exist - we need the political will and #leadership to make our streets safe for all. pic.twitter.com/MbTlARHAnm

— César Zuñiga 塞薩爾 🚵🏽♂️ (@zuniga_nyc) October 7, 2020

Third Avenue below the elevated Gowanus Expressway between 18th Street and 54th Street is an infamous death trap — it has three lanes of traffic heading north and another three heading southbound. South of 54th Street, the configuration is different: two lanes of traffic on a service road on each side of the expressway, and five high-speed lanes directly underneath the highway.

Drivers and truckers often avoid the gridlocked Gowanus by using Third Avenue, turning it into a dangerous speedway. And it's even more perilous at night, when the avenue, which is riddled with potholes, double-parked cars, and car washes with vehicles jutting out, is enshrouded in darkness because of the expressway above it.

Locals warn that Third Avenue is only expected to get worse before it gets better as private developers are planning to build the country’s largest last-mile truck distribution center in the neighborhood some time this year, making it even more imperative that the city fix the deadly roadway now.

“Third Avenue is really dark. The streets are in disrepair and there are a number of things that can be done almost immediately to make it a safer place before we even get the greenway going," said Elizabeth Yeampierre of UPROSE, a Latino community-based organization that promotes sustainability and resiliency.

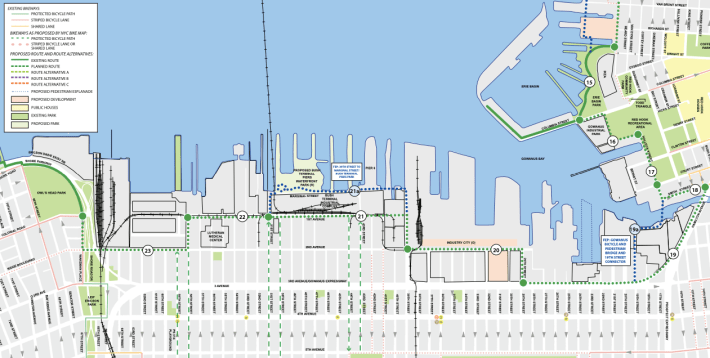

Thankfully, there is a plan — one that dates back to 2005, when Rep. Nydia Velázquez secured the $14.6-million federal grant for the entirety of the greenway, including a portion of Third Avenue south to 29th Street, where the protected bike path (see map below) turns west towards the waterfront instead of continuing down Third Avenue.

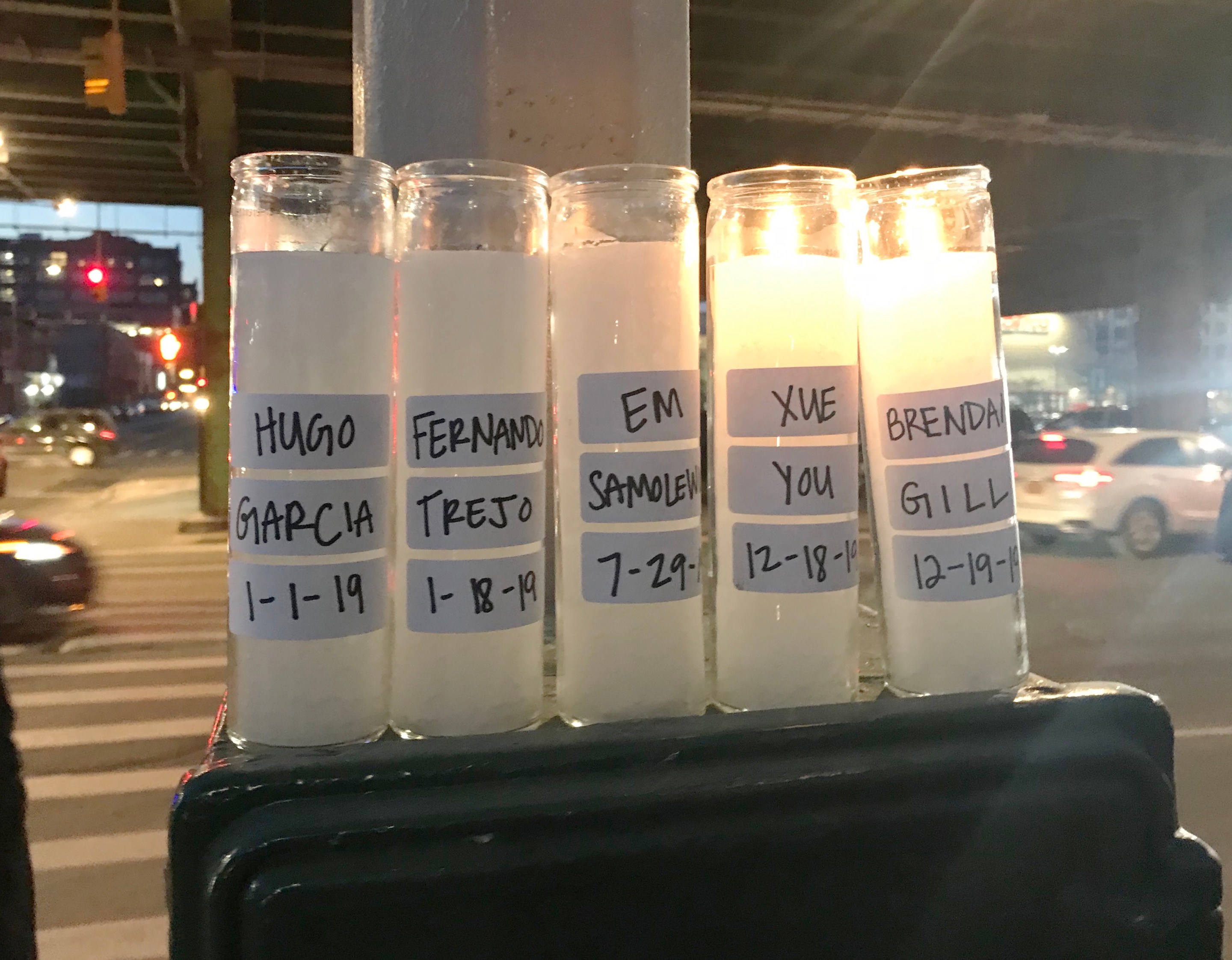

Kang's death was mourned at a vigil last month featuring many of the same people who had gathered late last year nearby for a vigil for the four people that had been killed along Third Avenue in 2019 — three of them south of 29th Street.

In December, a truck driver killed 85-year-old Brendan Gill near 39th Street; in July, the driver of a tractor-trailer fatally ran over 30-year-old Em Samolewicz after she was doored into traffic near 35th Street; and in January, drivers killed 27-year-old Fernando Trejo near 52nd Street, and 26-year-old Hugo Garcia near 28th Street.

But Yeampierre says she's not shocked that the city's greenway plan wouldn't dare go deeper into Sunset Park, where many of the neighborhood's immigrant and low-income families live, and instead include only the area that's now referred to by real estate brokers as Greenwood Heights.

"Low-income communities of color get treated differently, they get different investments in infrastructure. I'm not surprised that it would end in a place we're not even calling Sunset Park anymore, even though it is," she said.

According to Census figures, the Sunset Park tracts between Hamilton Avenue and 33rd Street have a median household income of $82,124 and are roughly evenly split, population-wise, between white and Latino people.

But in the tracts between 33rd and 60th streets — where no safety work is being conducted — the median income drops to $48,996, and the ratio of Latino to white people increases from 1:1 to 5:1.

And as Streetsblog has reported previously, the richest and whitest neighborhoods in town have the best bike infrastructure. In the Bronx, for example, bicyclist injuries are up 42 percent this year — the highest of any borough. The borough lacks high-quality, widespread protected infrastructure. It is also by far the poorest of the five boroughs of New York City.

Yeampierre says UPROSE's own plan for the greenway, which dates back to 2008, focuses more on building out protected pathways that connect all of Sunset Park's communities to the waterfront — not just one that only looks nice next to the water.

"We think greenways should connect communities, not just wrap around the waterfront," she said.

So far, only the less-dangerous parts of the full greenway project have been built: West Street, Columbia Street and in Brooklyn Bridge Park. The city is currently working on the Owls Head Connector, Flushing Avenue, Kent Avenue South, and Second Avenue near Industry City and the Bush Army Terminal.

The just-begun work on the upper part of Third and Hamilton avenues — a bike lane on the southern side of both roadways between Smith and 29th streets — isn't expected to be completed until the fall of 2022, or 17 years after the federal government funded the project and five years after the DOT initially said it could finish the work, according to this 2014 presentation.

The DOT says all the funding has now been allocated towards the project, but that work was delayed due to "several funding and design issues, as well as delays related to COVID-19."

Velázquez blasted the city for failing to start work sooner after she worked hard to get the funding 15 years ago.

“Here we are again and again. Too many times we have come together [at vigils]. The city of New York, the state and federal government, must come together to make sure that our communities are safe,” Velázquez said. “I secured money, and I don't want to go through that again. Vision Zero means nothing if we cannot implement these most basic measures to make sure our children, workers, everyone is safe. It’s not about sitting around, it’s the process, the bureaucracy to move all this money, that is the part that is frustrating.”

The federal pol demanded that the city "come up with some other money" to provide safety further down Third Avenue. But DOT says the only greenway expansion planned for Sunset Park includes 29th Street between Second and Third avenues, and Second Avenue between 29th and 39th Streets (as shown in the map above).

Since 2005, the city has done some work to make Third Avenue safer, like lowering the speed limit late last year from 30 to 25 miles per hour, installing speed cameras, and improved pedestrians crossings. DOT also installed a two-way protected bike lane on Fourth Avenue between Atlantic Avenue and 64th Street. But it clearly hasn’t been enough, activists say.

"I want to see an end to political pageantry like this and for the people that say they're gonna fix something to actually do it," said Sunset Park resident and transit advocate Jorge Muñiz-Reyes. "Put some lights under there, get rid of some of the cars, maybe put a busway, fix it. Make sure it's not dangerous. I want to see our neighborhood get better safer, stronger."

“This is where I learned how to ride my bike,” says @jmunizreyes. “This was an essential healer. A lot of promises were made to fix Third Avenue. Third Avenue doesn’t look fixed to me. Nothing had changed. I want to see an end to political pageantry like this.” pic.twitter.com/wTMdvCbII1

— SunsetPark1890 #NotMeUs 🌹🌈🌍 (@sunsetpark1890) October 6, 2020

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story conflated two things: The Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway is the public infrastructure being built. The Brooklyn Greenway Initiative is a private, non-profit organization dedicated to the development, establishment and stewardship of the Brooklyn Waterfront Greenway.