Updated | This story was updated at 7:35 p.m. on Monday to reflect new information from the NYPD.

The NYPD has made thousands of crashes on Staten Island simply disappear — and now is poised to do the same thing for the entire city.

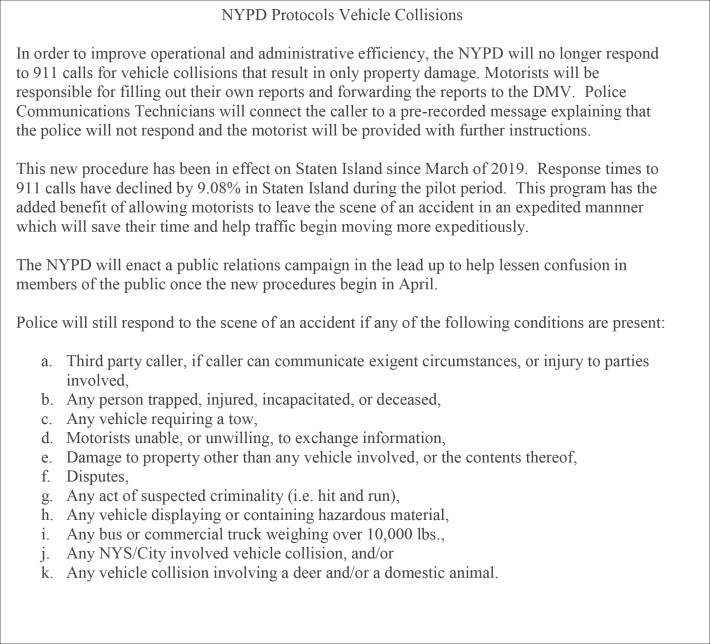

Streetsblog has learned that the NYPD has quietly floated expanding a pilot program begun last year on Staten Island that calls for officers to no longer respond to automobile crashes involving only minor property damage — fender-benders, if you will.

"NYPD will no longer respond to 911 calls for vehicle collisions that result in only property damage," the agency told lawmakers this morning (Streetsblog saw the note). "Drivers will be responsible for filling out their own reports and forwarding the reports to the DMV."

It would represent an expansion of a policy that has been the subject of virtually no discussion outside the ranks of the NYPD. Last year in New York City, there were 165,707 crashes that did not cause injuries, roughly 450 per day.

So how well did the pilot program perform? The NYPD declined to discuss the program, but two data points stand out:

First, the practice dramatically deflates the number of non-injury crashes that show up in city stats:

- In the year defore the pilot went into effect (March 19, 2018 to March 18, 2019), there were 9,571 total non-injury-causing crashes recorded by NYPD in Staten Island, according to city data.

- In the year after (March 19, 2019 to March 18, 2020), the NYPD reported only 3,640 non-injury-causing crashes in Staten Island, a decrease of 62 percent.

Obviously, if there had really been a 62-percent drop in crashes on Staten Island, authorities would be taking a well-deserved bow. But here's why no one is: The number of crashes in Staten Island was likely roughly the same during the comparable March-to March-segments. The only difference is that on March 18, 2019, the NYPD announced quietly that it would stop responding to what it called "minor fender-benders."

The second data point is a claim by the NYPD — which did not provide supporting evidence — that emergency response times on Staten Island have improved 9.08 percent.

The NYPD said it changed its policy on Staten Island because there are so many crashes on Staten Island — roughly 32 per day — that officers were becoming overwhelmed with paperwork.

“That's a tremendous number of hours that could be spent on working on something else, and if we're talking about improving response times to emergency situations where seconds count, it could be very significant," the island's top police official, Assistant Chief Kenneth Corey told NY1, which reported on the new policy last year.

The number of crashes with injuries also dropped a bit after the policy went into effect — from 2,074 to 1,809, or 12.8 percent less — but citywide crashes with injuries were down about 5 percent over the same period.

The NYPD declined our initial requests for comment, but after publication of this story, NYPD Spokeswoman Devora Kaye said, "The NYPD is reviewing ways to help police officers respond to critical situations faster while keeping New Yorkers safe and saving them time."

She said the Staten Island pilot "has proven successful for officers and residents."

She added a citywide expansion is pending once "New Yorkers are educated on the proper steps should they be in a vehicle collision."

There is no question police officers spend far too much time attending to motorists who damage their vehicles or other people's property through errors or recklessness. According to lawyer Steve Vaccaro, the time has long come for taxpayers to no longer play a role in how private property owners settle disputes of their own making. As such, he hailed the new policy.

"It's absurd that public resources are being used to provide loss adjustment services for free for the insurance industry," Vaccaro said. "It's yet another externalized cost that drivers put on the rest of us. You want to store or move your $50,000 piece of private property through the public right of way, you should pay the price of the [insurance assessment]."

City Council Member Justin Brannan also said he saw positives in the policy change.

“It’s a strange time for a policy change like this, but it makes sense," said the Bay Ridge Democrat. "People often complain that it took the cops three hours to show up to the scene of their fender-bender, but that’s because cops are out fighting actual crime and responding to real emergencies. If no one was injured, move your car out of the way so you’re not blocking traffic. It’s a fender-bender not the JFK assassination. You don’t need the cops for this. Let’s get it together, folks."

That said, the potential for fraud increases when officers are not part of the equation. In 2006, then-Attorney General Eliot Spitzer put out a report showing how easily fraudsters were perpetrating a scam outside the eyes of cops by steering fake crash victims to shady doctors. Insurance fraud remains a problem.

The "disappearance" of thousands of crashes from city crash data should not be a cause for alarm among street safety advocates, either, said Jon Orcutt, a former city DOT official who now works at Bike New York. He said that city officials only look at serious crashes — those with a serious injury or a fatality — when making decisions about road redesigns.

But it is still raised the possibility of confusion if intersections in Brooklyn showed large numbers of crashes and similar intersections in Staten Island appeared "safe" because police officers never responded to the crashes that occurred there.

After initial publication of this story, the city Department of Transportation issued the following statement:

DOT's Vision Zero work has always been guided by data, particularly killed/seriously injured statistics more than minor crashes. We are in constant communications with NYPD at the borough and precinct levels on any issues that may arise as well as gathering feedback on specific locations. And as you are probably already aware, Staten Island has seen single digit fatalities in the last two years and we hope to continue limiting serious injuries and fatalities throughout the borough and city-wide.