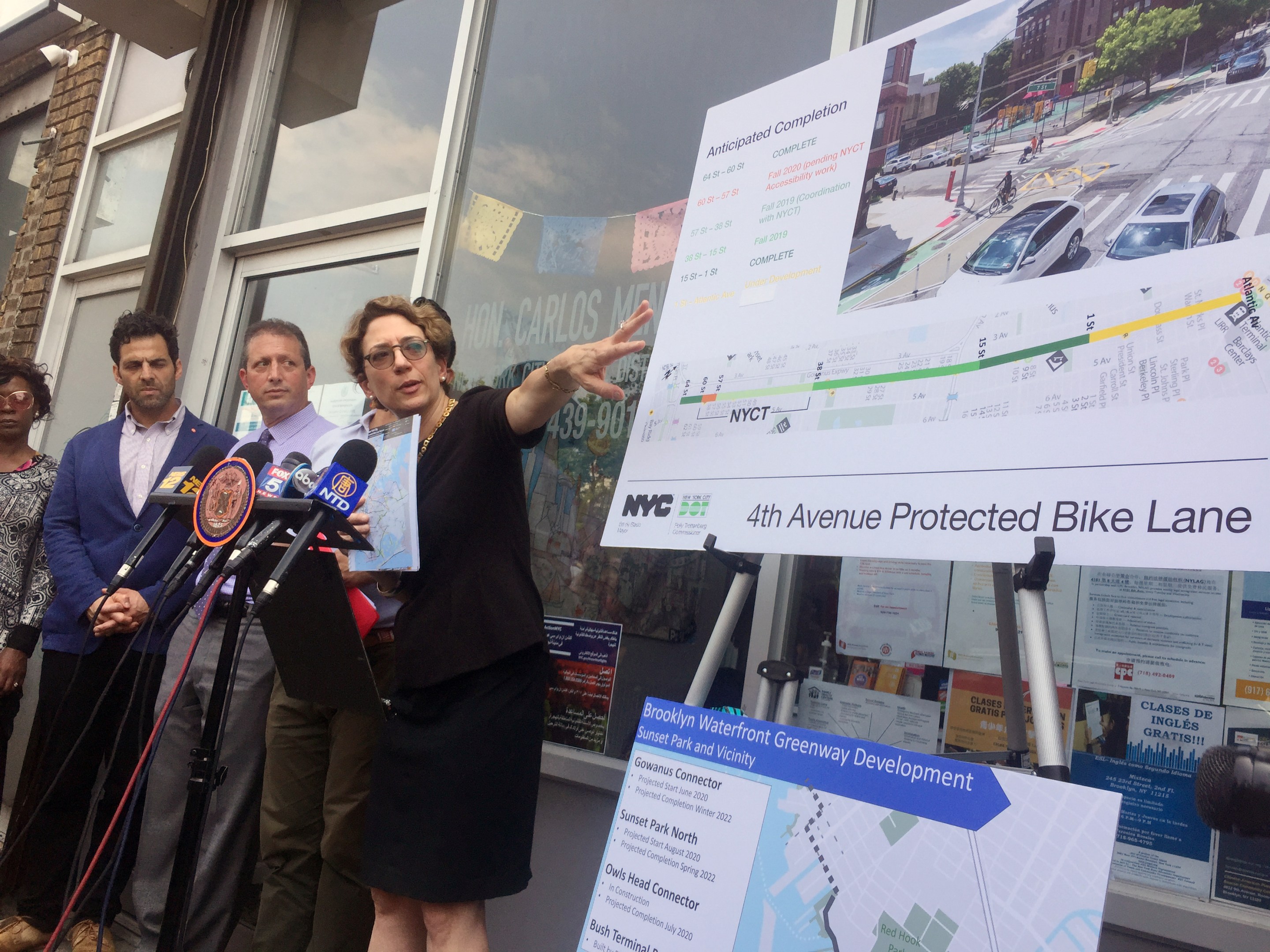

Department of Transportation officials took a victory lap in announcing on Wednesday that they would expedite a long-promised protected bike lane on Brooklyn's Fourth Avenue only to be reminded of activists' frustration over the agency's Achilles heel: gaps in protected infrastructure that suddenly throw cyclists back into traffic.

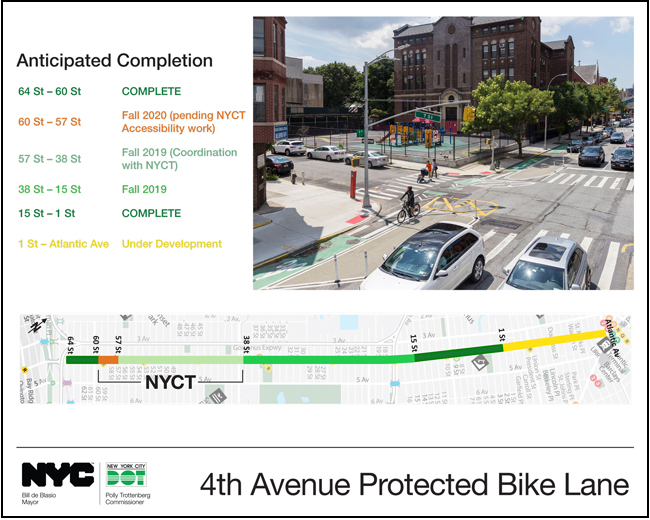

The good news heralded by DOT Commissioner Polly Trottenberg — namely, that cyclists will get near-complete protection from First Street to 60th Street this year as opposed to several years from now — was punctured by an admission that the DOT plan [PDF] does not currently include a stretch between First Street and Atlantic Avenue, which activists believe is a key piece of a bike route that could eventually protect cyclists heading through Park Slope and Fort Greene to the Manhattan Bridge.

Council Member Brad Lander of Park Slope, a strong supporter of protected infrastructure, pointed to the DOT map and highlighted its main shortcoming — coming just a few days after he attended a memorial on neighboring Third Avenue for cyclist Em Samolewicz.

"You see some yellow on the right side of this map and it cannot stay yellow very long because I don't want to be standing at a vigil because someone got killed because we did not move fast enough to get a safe protected bike lane the rest of the stretch," Lander said. "The plan does not have a clean, firm protected bike lane for that stretch. We need to get it and we need to get it as soon as we can."

Trottenberg said the agency is still "figuring out how we can that protected infrastructure all the way to Atlantic Avenue."

"That is our commitment, she added, "hopefully next year if we can, but stay tuned."

For the most part, of course, advocates hailed the city's plan for Fourth Avenue, which will create miles of safe roadways for cyclists.

But the successes and shortcomings of the Fourth Avenue project are a fitting metaphor for a city that is fighting a political civil war over a safe, sustainable vision of the public roadways. On Fourth Avenue, Trottenberg has the strong support of not only the local elected officials — Lander and Carlos Menchaca — but also many community groups and activists that are actually calling on her to move more aggressively to make roads safer.

And since Mayor de Blasio announced his cycling safety program expansion, several council members — most notably Jimmy Van Bramer — have asked the city to send those "Green Wave" waters flowing their way.

Meanwhile in so many other neighborhoods — where the council members are named Koslowitz, Deutsch, Diaz Sr., Treyger, Yeger, Gjonaj — Trottenberg faces politicians who not only oppose her life-saving street safety improvements, but actually organize communities and community boards against them. Streetsblog pointed out to Trottenberg that a bike lane in Menchaca's district is the low-hanging fruit — and asked about her plan for the harder-to-reach crops.

"You are right," Trottenberg said. "We are going to go into a whole lot of neighborhoods where there is not only intense opposition, but in some cases we are being sued. At DOT, our role is to design the best projects and to work with local communities. ... But we [also] look to the leadership of council members. Maybe it's not their district, but from the Speaker on down, the Council has sent us a strong message: they want to break the car culture in New York, and want to see much more aggressive Vision Zero projects and we hope they'll be a part of that dialogue. ... It is collective responsibility."

Trottenberg also did something rare (for her). She then called out a specific neighborhood that has resisted her efforts at its own peril, though she did not call out Council Member Kalman Yeger or longtime (though now ex-) Assembly Member Dov Hikind by name.

"What breaks our hearts is that there are some neighborhoods — Borough Park, I'll mention one — where we saw a tragic fatality this summer. I can safely say there is not great enthusiasm [from the elected officials] for the work we want to do over there. Those are places where I hope collectively we can come together. To do what we've pledged to do in this plan, a connected network for the whole city, we're going to have to be everywhere."

Menchaca said he and Lander function as ambassadors to sway car-biased lawmakers.

"We talk to them to find out what is at the heart of the resistance," he said. "It's about fear, misunderstanding and a different orientation. But all of that can change. It will change with conversations."

Lander recalled that when he joined the council in 2010, the chairman of the Transportation Committee was James Vacca, a Bronxite who did not support street safety initiatives (his successor, Mark Gjonaj, has maintained the tradition). But by the time he left the council in 2017, Vacca was a convert.

"Over time, you can see his mind has been changed," Lander said. "That's a person you would have seen on that list of council members who oppose street safety. ... He's come to think differently on these issues because of the organizing work. We have all evolved."

Make that some. The conversation about Fourth Avenue naturally dovetailed to a discussion about the rollout of DOT's vital residential loading zone program, which has seized back curbside space from private car owners to make room for trucks to make deliveries in residential neighborhoods — which have skyrocketed in the online retail era. Many car owners have pushed on the program because it means that there will be less room for them to store their cars for free — but street safety advocates hail the project because it will mean fewer trucks parked unsafely in the roadway.

Trottenberg admitted that she could use some political support for the program.

"Some neighborhoods have been embracing it," she said. "Some neighborhoods, not as much as we would hope."

Seeing a new front in the city's civil war, Streetsblog pressed Trottenberg that she needs to do more.

On residential parking, you are getting pushback from car owners who believe that the curbside space belongs to them, in many cases for free. So isn't it time for the DOT to push back on that notion, as Community Board 7 is on the Upper West Side is saying, "You know what, the curbside is public space. It does not belong to private car owners to put their cars there, mostly to be stored, as your own studies show, up to 90 percent of the time. Can you do more, actively, to aggressively change the conversation about the notion of on-street car storage?

"We can always do more," Trottenberg started. "The point of this pilot — as with Citi Bike and car share and more bus lanes and more bike lanes — is the idea that we can use the street space much more efficiently. ... Certainly with this loading zone pilot, I won't lie, we can use some political support. But we are exactly trying to send that message."

Perhaps it needs to be sent louder, when even a protected bike lane project that's being expedited in a year with 18 cyclists deaths still has a 15-block gap in it. Or Queens Boulevard isn't complete. Or the city gets sued by some of the wealthiest Upper West Siders when it proposes to build a bike lane on Central Park West.

"One of the fastest ways we can get to that vision of safe streets is to hit the idea of free parking head on," Menchaca said. "Elected officials who want to keep doing this work should champion that issue if they are truly for safer streets."