Governor Cuomo is literally all over the subway map.

Speaking on WNYC on Monday, Cuomo claimed to be "against" a fare hike that's long been scheduled by the MTA for next year — as if he has no control over it. Then he argued that MTA officials "have to do more" even as he once again championed a congestion pricing plan to raise billions for the agency.

"The MTA’s first job is to look within," the governor told host Brian Lehrer, rhetorically sidestepping his own authority over the state agency. "There is waste, there is inefficiency that currently goes on at the MTA that has to end.

"I don’t control the MTA board," he added. "They have to do more."

Then he vowed to fix it.

It's hard to know where to start with obfuscation like that.

In addition to controlling six of the board's 14 seats, the governor hand-picks its chairperson. Cuomo wades into the agency's internal workings as he sees fit, whether picking specific tiles in its tunnels to match the state's official colors or redirecting the agency's dollars towards bailing out upstate ski resorts. In 2014, when the agency's largest union contract was on the line, Cuomo put himself front-and-center. And no one made sure he was more identified with the completion of the Second Avenue subway than Cuomo, despite billion-dollar cost overruns that somehow he never got blamed for.

And Cuomo is now using its structure of obfuscation to obfuscate.

— Vincent Barone (@vinbarone) November 19, 2018

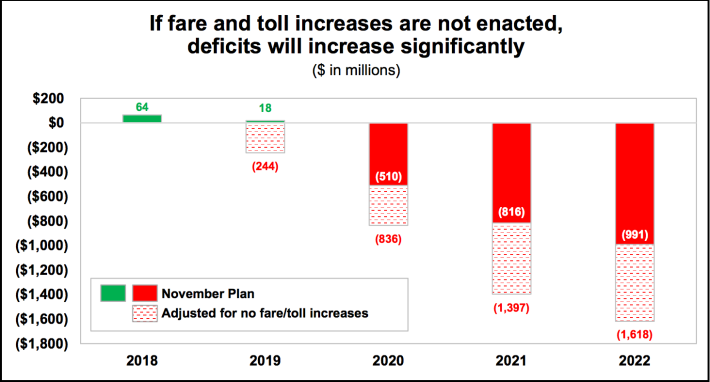

Congestion pricing, meanwhile, is expected to net around $1 billion per year, enough to cover the MTA's operating deficit through 2022 — provided that it goes ahead with scheduled fare and toll increases [PDF - Page 14]. Without fare hikes, the annual deficit will grow to $1.62 billion. And that's not even getting to the agency's longterm capital needs, which are expected to top $60 billion.

Last week, the MTA board confirmed that the New York's mass transit system is on the cusp of a death spiral. Officials anticipate huge operating deficits in the near-future. Meanwhile, ridership is down — in large part due to off-hour service cuts and line closures meant to speed up maintenance.

The anticipated fare increases, which the agency committed to regularly enacting nearly a decade ago during a previous financial crisis, will likely compound that downward trajectory.

Some observers, like the Daily News editorial board, insist that fare hikes are a fiscally responsible, necessary evil, but transit advocates are asking why the burden of bailing out the MTA falls on the backs of working-class New Yorkers rather than all taxpayers, as everyone benefits from the transit system, even its non-users.

"We all bare the costs of a declining system, but low-income and middle-income fare payers bare those costs the most," Riders Alliance spokesman Danny Pearlstein said. "If you raise the fare now, the people who can least afford to do so are asked to pay more and more for less and less."

Still, other funding sources will be hard to find, according to Jamison Dague, analyst at the Citizens Budget Commission. Federal support is a thing of the past; the leaves politically challenging tax increases as the main untapped funding stream. Without an influx of revenue, everyone is going to have to chip in — riders, drivers, and workers.

"There’s not a whole lot of leeway as far as other places to go as far as revenue sources," Dague said. "It’s a shared sacrifice that’s going to be necessary."