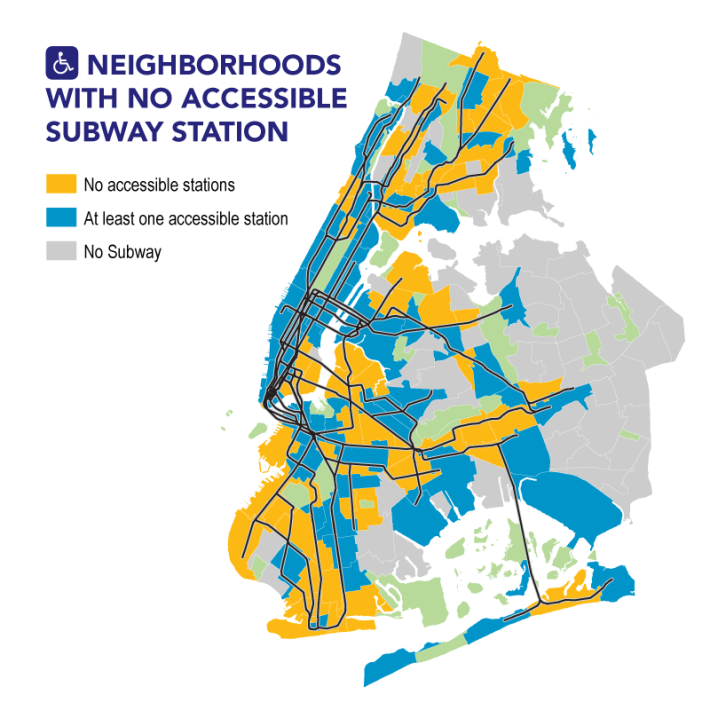

Only 24 percent of subway stations are accessible for people who can't use stairs or escalators. And less than half of the neighborhoods served by the subway have at least one elevator-accessible station, according to a new report from Comptroller Scott Stringer.

That's on a good day. Elevator outages and malfunctions are commonplace, making even the accessible parts of the system haphazard and unreliable.

What might be a 10-minute subway trip for most New Yorkers can take three hours for people with mobility impairments, Monica Bartley, an organizer with the Center for Independence of the Disabled NY, told the audience at a TransitCenter panel last night.

A few weeks ago, Bartley and her colleagues were on their way back to Union Square from a meeting with MTA officials four stops away at Bowling Green. When she got off the train, she learned that the 4/5/6 platform at Union Square is not elevator-accessible. She was advised to head to Grand Central. "When I got to Grand Central, the elevator there was not working," she said. "I went back and headed for Brooklyn Bridge, then I discovered that one was under construction."

Multiple trains and many hours later, Bartley was back in the Financial District at Fulton Street. She ended up taking the bus to Union Square.

"Whenever we plan to travel, we always have to plan for a lot more time than it would take someone normally to travel around the city," she said.

Improving accessibility is one of the four topline priorities in Byford's subway action plan, released in May. Over the next five years, the MTA plans to make 50 more stations accessible, so that wheelchair users are never more than two stops away from a station with an elevator. Byford has hired former TLC accessibility program manager Alex Elegudin to steer the agency's accessibility mission.

In addition to retrofitting stations with elevators, Byford's accessibility priorities reflect TransitCenter's #AccessDenied campaign: hiring staff with first-hand experience of the subway's accessibility shortcomings, improving the reliability of elevators, and a "streamlined" design-build approach to elevator installation.

Panelists pointed out that accessibility doesn't end with elevators. The width of platforms, the gap between platforms and trains, bus stop snow removal, and the clarity of audio and visual service announcements are all daily concerns for subway riders with disabilities.

Bartley and other disability advocates in the room applauded Byford's commitment to accessibility, but they challenged him to codify it legally.

Nearly three decades after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the MTA has dragged its feet compared to peers in Boston and Chicago, where about 70 percent of stations are accessible and the number is rising. The MTA is currently in the process of settling a class-action lawsuit filed by the organization Disability Rights Advocates related to recent station renovations that did not include accessibility upgrades.

"Fifty stations in five years... that is a very aggressive pace," panelist and Disability Rights Advocates attorney Emily Seelenfreund said of Byford's plan. "All we ask of Mr. Byford is to 'put your money where you mouth is,' and to enter into a court-enforceable, binding settlement agreement to make those stations accessible."

"As we know, the MTA is a public entity and priorities can change," she said. "We don't want this priority to change. We want it to be the letter of the law."