City Council members Ydanis Rodriguez and Mark Levine want to institute residential parking permits in New York City.

Their proposals are light on details, which would mainly be left to DOT to determine, but one thing is clear: The motivation for the bills is mostly about appeasing complaints from car owners who feel that out-of-city residents are infringing on their turf. Rationalizing New York's free parking giveaway isn't the point.

One bill, from Transportation Chair Rodriguez and Stephen Levin, would require DOT to implement a citywide residential parking permit system. The other, sponsored by Levine, Helen Rosenthal, Diana Ayala, and Keith Powers, would create a permit system in Manhattan above 60th Street only.

By discouraging non-residents from driving into the city, the council members argue, residential parking permits, or RPP, would reduce the number of vehicles on city streets.

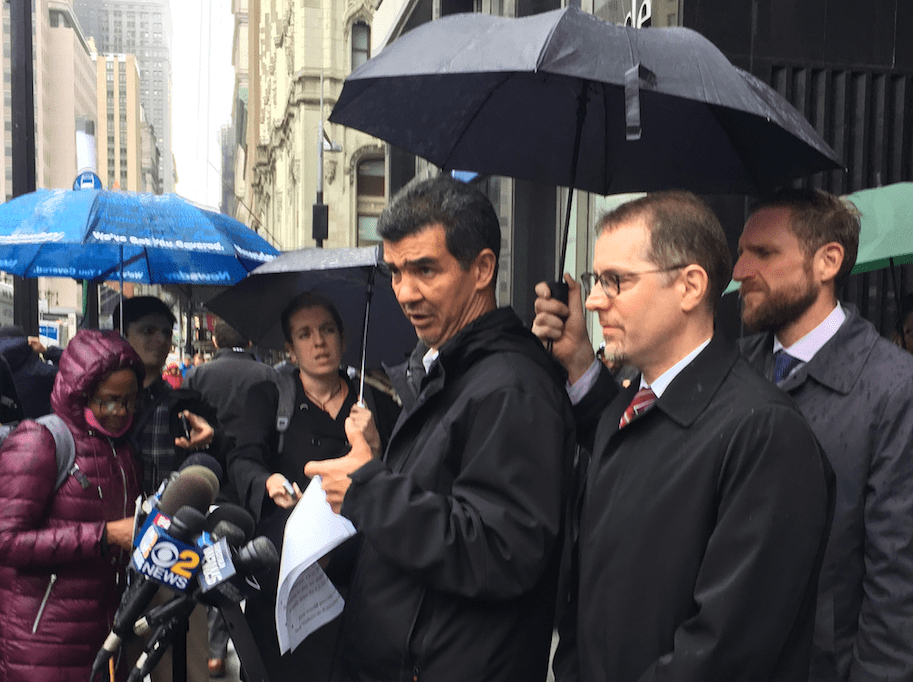

"[Congestion] is a problem that's just getting worse by the day, and it's being driven by [drivers] coming in from other parts of the region, who are dumping their cars on our streets to hop on mass transit," Levine said at press conference with Rodriguez. "Commuters from other parts of the region do not have a God-given right to park for free on our residential streets."

But the council members didn't offer any evidence that park-and-ride behavior on residential streets contributes substantially to city traffic. And even if park-and-ride trips are an issue in some neighborhoods, their bills would not address it: 20 percent of spaces in RPP zones would still be reserved for non-residents.

In general, not much thought has gone into how the permits would work. The main cause of the parking crunch in NYC isn't the lack of a permit system, it's the combination of finite curb space and free parking. With off-street parking typically costing hundreds of dollars per month, on-street spaces are always going to be crammed full as long as they're dirt cheap.

The price of the permits won't change that calculation. Rodriguez said he'd expect the annual fees to be around $150 or $250, or about $12-$20 a month -- pocket change compared to garage rates.

Cordoning off parking spaces just for residents raises a lot of other questions, like how contractors doing business on residential streets fit into the system. When the Bloomberg administration was developing a congestion pricing plan in 2008, DOT laid out scenarios for RPP that would address those nuances. The bills introduced by the City Council leave those details for later.

The regime the council envisions would link each permit to a New York driver's license and a specific license plate. DOT would designate areas where residential permits would be in effect, in consultation with local council members and community boards. Further details would be determined by DOT through the official rule-making process.

The last time the City Council took up parking permits, in 2011, DOT said that RPP alone wouldn't significantly affect traffic. (The council ignored City Hall's objections and overwhelmingly passed a resolution endorsing state legislation to enable a permit system. Then nothing happened in Albany.)

The best that can be said for RPP with low permit fees is that it might cut down on insurance fraud by compelling NYC residents to register their cars in New York, instead of cheating the system by registering in lower-cost states like Pennsylvania and North Carolina.

The other theory is that any change in the direction of regulating car storage on public streets is better than the status quo. Transportation Alternatives Executive Director Paul Steely White said the bills could indirectly generate momentum for smarter parking policies across the city, including dynamic curbside pricing on commercial blocks to encourage turnover and more dedicated space for deliveries.

At some point, Albany will probably have to get involved in enacting an RPP program. Every other city in New York with RPP got enabling legislation from the state, but the council's lawyers believe the city can implement permits on its own. Even so, Brooklyn Assembly members Jo Anne Simon and Walter Mosley are willing to put forward authorizing legislation, Rodriguez said.