Here's some great news out of Center City Philadelphia: Housing is replacing parking.

The number of off-street parking spaces in downtown Philly and nearby neighborhoods declined 7 percent between 2000 and 2015, from about 50,000 to 46,400. As parking became less abundant, the appetite for it also waned: Parking occupancy rates have fallen almost 2 percent over the same period.

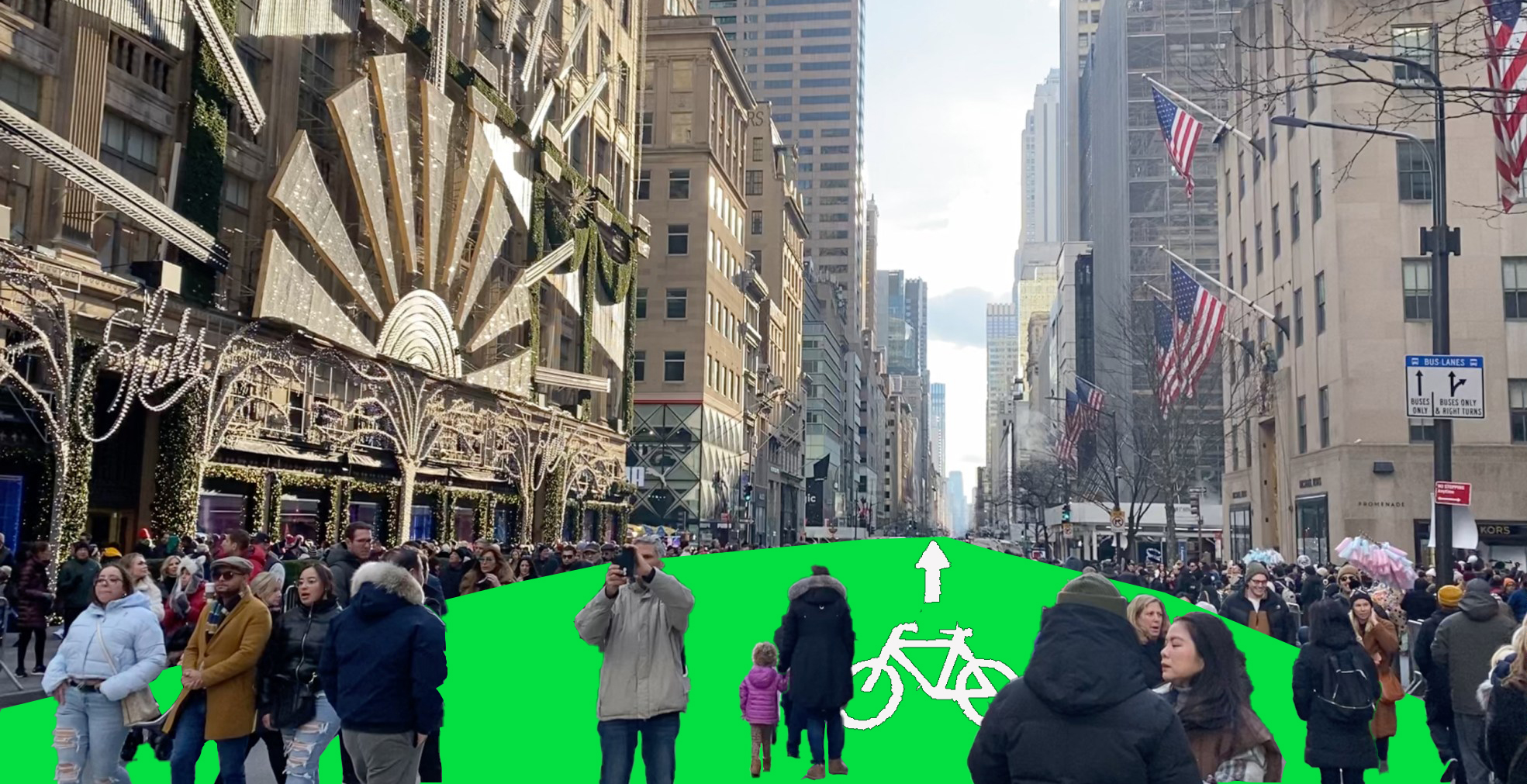

What's happening in Philadelphia is evidence of the "virtuous cycle" that results from reducing dependence on cars. Making parking less convenient is leading to greater walkability.

It's also the result of deliberate public policies -- mainly tax incentives, with a dash of zoning -- which Jonas Maciunas of the Philadelphia-based urban design consultancy JVM Studio described in a presentation at UConn earlier this month. Other cities scarred by excessive parking in central neighborhoods should take note. If, like Philadelphia, there's demand for growth downtown, these four steps can channel it to create more walkable places.

1. Raising the parking tax

Philadelphia levies a surtax when people pay for off-street parking. Between 2007 and 2015, the city incrementally raised this tax from 15 percent to 22 percent, making parking more expensive for consumers.

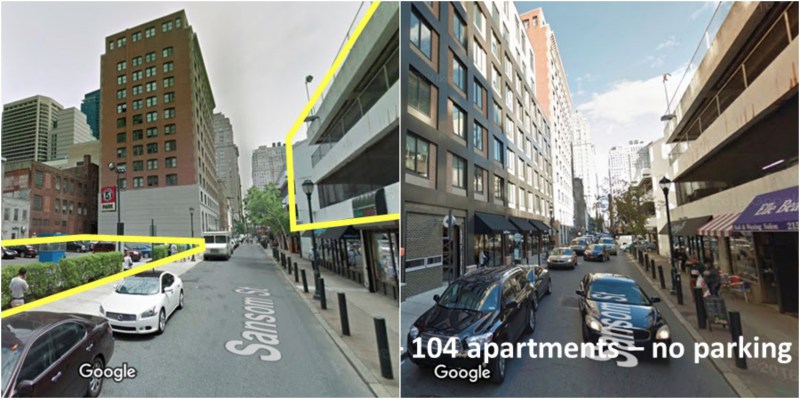

2. Reducing parking minimums

When a parcel is developed in central Philadelphia, the zoning code makes it easier to build for walking, not driving. In 2012, the city eliminated parking minimums for commercial buildings in the center city. It also dramatically reduced residential parking requirements. For every 10 residences, the old rules required seven parking spaces, while the new rules require three.

3. Tax abatements for new construction

In 2000, Philadelphia enacted a tax abatement to attract development, which had been flowing mainly to the suburbs. The city granted a 10-year property tax exemption on improvements to residential and commercial properties. New or renovated buildings are tax-exempt, while the land itself is not.

Obviously, the abatement alone would not work without market demand. Nor would it be necessary if the market was already primed to build. But in Philadelphia's case, it appears to have helped tip the scales, coinciding with a shift in development patterns, according to data from the Building Industry Association of Philadelphia:

4. Reassessing property values

In 2013, Philadelphia changed the way it assesses property values and updated all 579,383 properties on its tax rolls through the "Actual Value Initiative." Some properties had not been reassessed since the 1980s, according to the Pew Charitable Trust.

The new assessment methodology places greater emphasis on the value of land in relation to structures. Last year, for instance, most properties -- 85 percent -- saw no change in total value, but 92 percent saw an increase in land value, reported Jon Geeting at Plan Philly. The 14 percent of properties where assessed value increased were concentrated in areas with hot real estate markets.

The effect has been to create incentives for construction. When land is taxed more relative to buildings, that encourages property owners to develop, rather than retain low-value uses like parking lots.