As the L train shutdown approaches and the release of a detailed plan of action from DOT and the MTA draws closer, the de Blasio administration is hesitating to take the necessary steps to prioritize buses and high-occupancy vehicles, according to internal planning documents obtained by Ben Kabak at Second Avenue Sagas.

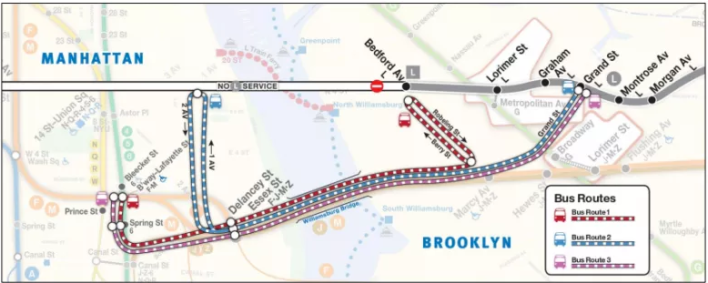

To keep transit riders moving when the western portion of the L train is out of commission for 15 months, starting in April 2019, the MTA will need to run a lot more buses, and those buses will need priority on streets between Williamsburg and the West Side of Manhattan.

Combined with high-occupancy vehicle restrictions on East River bridges, bus priority treatments have helped keep New Yorkers moving during previous events when a significant portion of the subway network was out of commission, like the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy. This requires disrupting the habits of motorists, and the big question for the L train shutdown is whether Mayor de Blasio has the political will to carry out the necessary changes.

The documents, which Kabak shared with Streetsblog, detail scenarios that DOT is considering to prioritize buses and high-occupancy vehicles during the shutdown. They do not represent final decisions made by agency staff or City Hall, but shed light on the thinking at DOT and the MTA and how far the city is willing to go to claim street space for transit. One caveat is that while the documents were produced in the past few months, they may not represent the current state of the city's internal planning process.

On the East River bridges, the scenario with the most impact on private car travel calls for allowing only vehicles with three or more occupants on the Williamsburg Bridge all day (and maybe overnight), and for HOV3 restrictions on the other three bridges from 5 a.m. to 11 a.m.

Other scenarios include making only the Williamsburg Bridge HOV3, or designating a bus- and truck-only lane in each direction on the Williamsburg Bridge. No scenario mentions combining HOV restrictions and bus lanes on the bridge.

The MTA's service plan, meanwhile, calls for running 60 buses per hour over the Williamsburg Bridge during peak hours. To keep those buses moving, they will need unobstructed travel not only on the bridge, but on the approaches to the bridge as well. While the documents show DOT considering bus lanes on Delancey Street (especially westbound) and other approaches, there is no indication of any firm commitment, though keep in mind that these questions may have since been resolved.

On 14th Street, where peak bus frequency would double to about one bus per minute, DOT is developing a plan for strong transit priority between Third Avenue and Eighth Avenue, with those treatments tapering off on each end.

On those five blocks, 14th Street would be exclusively for transit, except for deliveries and private vehicles getting to and from garages, which would be expected to use only the block of the busway closest to their destination.

Between Third Avenue and First Avenue, 14th Street would have standard painted bus lanes and other traffic would be allowed. And between Ninth Avenue and Eighth Avenue, eastbound buses would operate in a transit-only right-of-way, while westbound buses would have a standard bus lane. West of Ninth Avenue and east of First Avenue there would be no transit lanes.

Officials are considering substantial sidewalk expansions along 14th Street, but they are not planning for bikeways. The demand for bike travel on 14th Street isn't going away, however, and without designated space for cycling, many people will opt to ride in the busway.

With the caveat that these are preliminary plans and may be a month or two behind the most current thinking at DOT and the MTA, they raise some red flags. Transit priority on the Williamsburg Bridge and its approaches in both Manhattan and Brooklyn, as well as the eastern portions of 14th Street, appears to be provisional at best in these documents. And while the central portion of 14th Street could be in line for strong transit-priority treatments, the agencies seem to be dodging the question of how to safely accommodate bicycling on the 14th Street corridor.

There's not much time left to get these decisions right. DOT and the MTA are expected to reveal a plan sometime next month, after election day.