“By denying responsibility for his transit system,” Brad Aaron wrote here last Friday, Governor Andrew Cuomo “is perpetuating a charade that has real consequences for New Yorkers.” That’s for sure. But can we express those consequences in dollars and cents? Can we estimate how much the ongoing degradation of transit service is costing us?

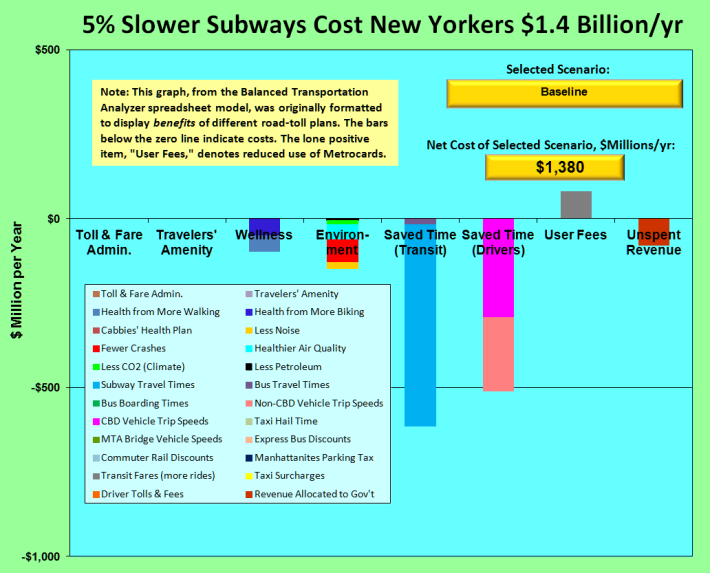

I believe we can. I’ve made a calculation of the cost of slower subways, and the number I’ve come up with, expressed on an annual basis, is $1.4 billion a year.

Most of that represents lost time -- straphangers’ time waiting on platforms and inside stalled and slowed trains, of course, but also drivers' time as wretched subway service motivates more driving, further worsening road congestion. And with more vehicles come environmental costs: more tailpipe emissions, and fewer opportunities for New Yorkers to safely walk and bike.

Averaged over every city resident, the $1.4 billion a year cost of subway slowdowns is equivalent to a new tax of three bucks per person each week, or $12 a week for a family of four.

To be sure, these figures don’t get at the human costs the way New York Times transit reporter Emma Fitzsimmons did a month ago in her searing front-page story, with its first-person accounts of missed appointments, job setbacks, and cascading frustration. My figure also omits longer-term costs of businesses and families abandoning New York (and fewer new ones materializing) as failing transportation becomes too much to bear.

Nevertheless, decisions on public spending can benefit from careful cost-benefit calculations. That’s where my BTA spreadsheet model comes in. Though I designed it primarily to model traffic-pricing scenarios like the Move NY toll reform plan, it’s equipped to analyze a wide range of transit and traffic scenarios. Here’s how I used it to put a price tag on subway slowdowns:

- In the absence of hard data, I assumed that the subways are now running 5 percent slower than in recent years. (If the true percent turns out to be different, just prorate my results.) Summed across the 1.76 billion subway trips last year, the extra minutes tacked on to subway journeys total around 36 million hours, which equate to $600 million in lost earnings and productivity.

- The BTA has a “time-elasticity” factor -- a relationship that says that each one percent slowing of subway service reduces ridership by around half a percent. Thus, the posited 5 percent slowdown would “disappear” 2.5 percent of the baseline 4.3 million daily subway trips to or from the Manhattan CBD, a loss of 108,000 daily trips.

- A lot of those 108,000 daily lost subway trips will switch to either for-hire or private vehicles. The BTA assumes that every 100 lost subway trips for work generate 70 new car or cab trips, and that 100 lost non-work subway trips give rise to 35 car or cab trips. The net result: a increase of 3-4 percent in the number of cars entering and occupying the Manhattan Central Business District each day.

- The higher volumes slow down traffic by 3 percent in the CBD and 1.5 percent on the network of roads and bridges feeding it, based on equations in the BTA that relate traffic volumes to speeds. Over the course of a full year, these prolonged vehicle trips add up to around 14 million hours, which equate to $500 million in wasted time.

- Increased auto use gives rise to environmental costs (principally, more crashes and pollution) estimated at around $150 million a year, and physical inactivity costs (reduced cycling and walking due to discouragement by higher traffic) that manifest as shortened life expectancies costing around $100 million a year.

Let’s do a reality check: If a 5 percent subway slowdown carries costs of $1.4 billion a year, then a 100 percent slowdown (i.e. loss of all service) should have a ballpark cost of $28 billion a year. That would equate to $3,300 per New Yorker, or $13,000 a year for a family of four, which doesn’t seem unreasonable.

So what is it worth to fix the subway slowdowns? If the solutions are only operational, then New York City Transit and the MTA should be willing to spend as much as New Yorkers are losing -- up to $1.4 billion a year. If capital investment is required, the MTA should be willing to lay out up to $24 billion (the capitalized value of an annual income stream of $1.4 billion, at 4 percent interest) in new outlays to cure the problems.