About 12 years ago, a coalition of advocates under the banner of the New York City Streets Renaissance set out to transform city transportation policy away from the car-oriented status quo and toward people-first streets. Streetsblog and Streetfilms have their origins in that campaign, propelling a growing public awareness that NYC doesn't need to settle for dangerous, traffic-choked streets.

The ideas promoted back then -- protected bike lanes, dedicated street space for transit, carving away traffic lanes for car-free public spaces -- seemed a little outlandish at the time, but many elements of that agenda have become official city policy in the years since. And yet -- the vast majority of NYC streets remain dominated by private cars.

While small interventions like signal changes, pedestrian islands, and safer markings have touched many neighborhoods, only a sliver of a fraction of city street space has been reallocated from cars to other modes. You're less likely to lose your life in traffic now than 12 years ago, but New York still doesn't have streets where, say, parents feel comfortable letting a child in elementary school walk a few blocks on their own to a friend's house.

New York can be a city where everyone from young kids to elderly seniors can get around without fear, where neighborhood streets can be places of congregation and activity instead of motorways. To become that city, we'll have to shift a lot more street space from cars to transit, biking, and walking.

Last night at the Museum of the City of New York, Streetsblog publisher Mark Gorton and Transportation Alternatives launched Streetopia, a campaign that aims to show what our streets are capable of when we no longer accept the primacy of the private motor vehicle. Here's the message in a 90-second Streetfilm:

Last night's event was a showcase for a maximal vision of street transformation -- where car-free street space is the norm, not the exception.

Parts of the city where transit access is high and car ownership is low are primed for car-free streets, says Mike Lydon of the Street Plans Collaborative, who displayed concepts for low-car, people first streets in Lower Manhattan, East Williamsburg, Downtown Flushing, and the Upper West Side.

In congestion-choked Flushing, Lydon proposes dedicating Roosevelt Avenue and Main Street entirely to buses and deliveries, while limiting other streets in the neighborhood to high-occupancy vehicles.

On the side streets of the Upper West Side, removing street parking would open up the street as a public space for walking, socializing, and play. Motor vehicles would be allowed, enabling essential deliveries or pick-ups/drop-offs for people who need direct access to paratransit, but traffic volumes would be very low and speeds extremely slow. Access to buses, shared vehicles, and protected bike lanes on avenues and major crosstown streets would be just a short walk away.

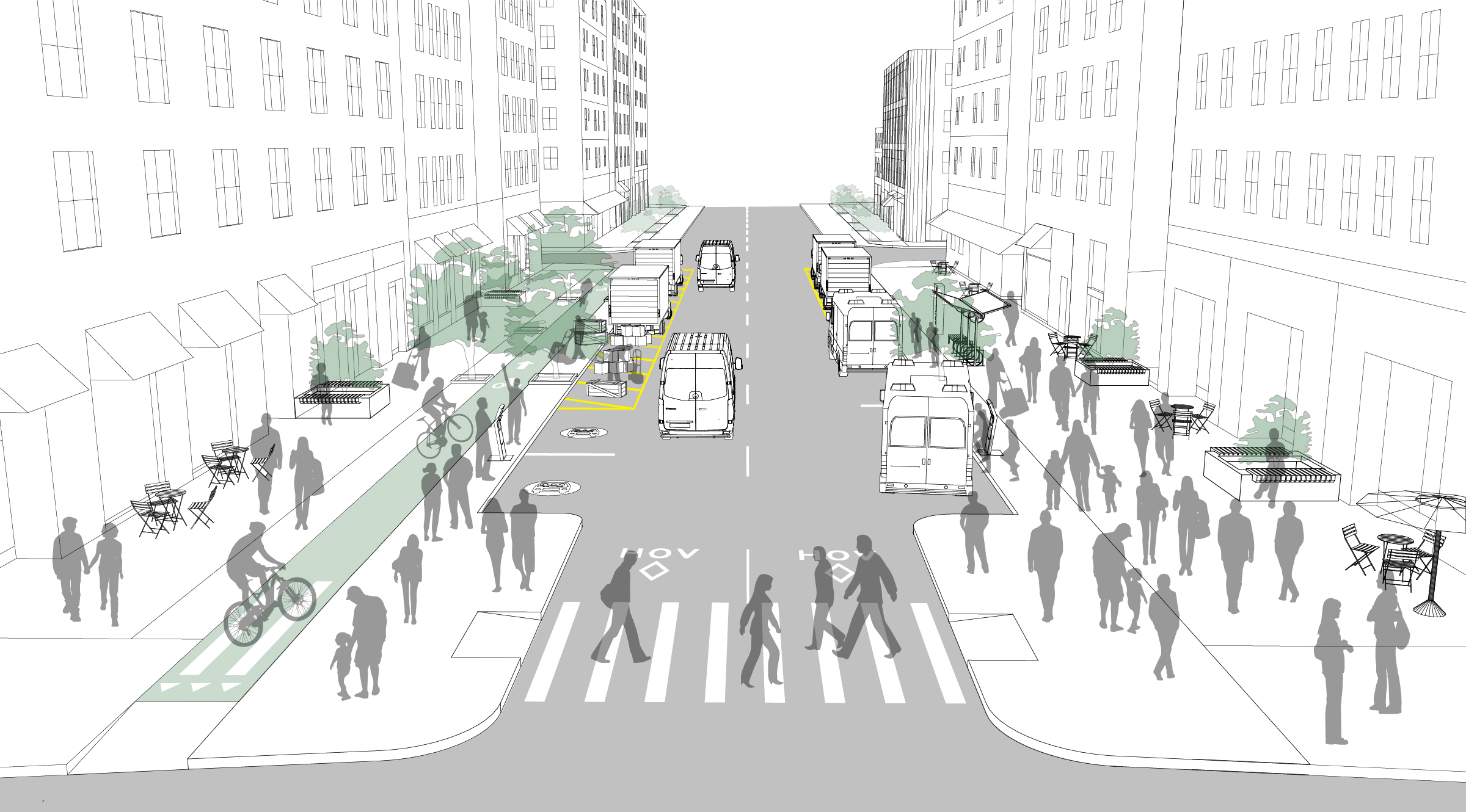

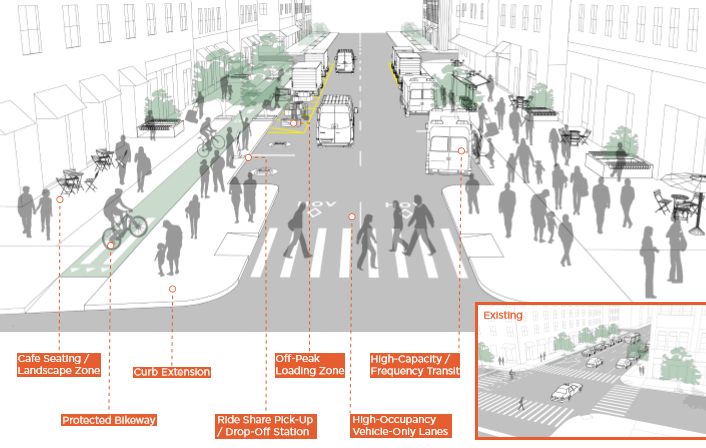

On major streets like Manhattan avenues or Grand Street in Williamsburg, Lydon's team proposes eliminating on-street private parking, adding protected bike lanes, and narrowing the roadbed for a two-way motorway where buses and high-occupancy vehicles would take precedence. Pull-outs in curbsides would be reserved for transit stops and deliveries.

In this transportation system, very few trips would be made by private vehicle. In Lower Manhattan, where cars are already pinched, the shift would not necessarily be that dramatic, but in other neighborhoods a concerted effort to reduce car use would be necessary.

"This plan implies serious congestion pricing, complete parking reform privileging not only ride-hail, taxis, pick-up and drop-offs, but also deliveries," said Lydon. "The vast majority of the space would not only be designed, but programmed and managed for the use of people."

It won't be easy to get to Streetopia. But if we don't put bold ideas out there, big changes will never happen.