The New York region's commuter rail network is failing to keep up with current travel patterns, said panelists at Friday's Regional Plan Association annual assembly. MTA chair Tom Prendergast agrees, but he doesn't expect that to change much anytime soon -- there are too many other priorities that need to be taken care of first, he said.

For generations, New York's commuter rail system -- Metro-North, the LIRR, and NJ Transit -- has been run to serve one primary purpose: carrying suburban commuters into the central business district in the morning and back home in the evening. But riders are increasingly using it for other purposes -- trips between boroughs, between suburbs, and at off-peak times.

RPA has some big ideas to re-orient commuter rail to meet the growing need for connectivity between places outside the Manhattan central business district. Among the proposals RPA is considering for its fourth regional plan, set to be released next year: one-seat rides between New Jersey, Long Island, and the areas served by Metro-North; an integrated regional fare system; increasing service within New York City; and third tracking the New Haven Line to allow for more local service between Connecticut towns.

RPA Vice President for Transportation Richard Barone said the MTA and NJ Transit have to change things up to meet new travel demands.

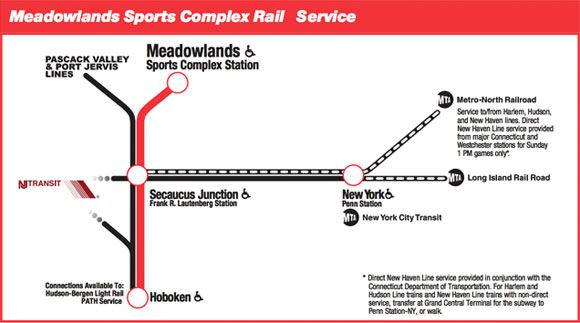

Running trains through Penn Station, for example, would open up the possibility of new service patterns. "When you hit Penn Station, you're at a dead end," Barone said. "It operates like a terminal even though, quite frankly, it's a station: you should be thinking of running service through it." (The commuter railroads already do this -- but only on very rare occasions, like Giants or Jets games.)

Within New York City, there are 36 commuter rail stations -- many in transit-starved parts of town -- but high fares and low service frequency discourage residents of surrounding neighborhoods from making intra-city trips. Re-orienting commuter rail service to be more appealing to city residents could ease the capacity crunch on some subway lines while cutting outer borough commute times significantly, Barone said.

Prendergast, whose agency encompasses the LIRR and Metro-North, responded positively to RPA's ideas, but did not see them happening in the near future.

Expansion projects often "take years that are measured in decades," he said. Several years passed before the politics of third-tracking the Long Island Railroad main line, for instance, reached the point where building the project seemed feasible. Now the MTA is playing catch-up. "We're behind the curve in the sense that the demand is occurring before we have capacity," Prendergast said said.

As for a regional fare system, first the MTA has to replace the Metrocard. Last month, the MTA put out a request for proposals for a new fare collection system. Prendergast said it's imperative for the new system to have no "technological impediments" to fare integration between rail operators.

The thorniest question is regional coordination between agencies -- Prendergast said he has more pressing priorities to deal with than getting the MTA and NJ Transit to take on the challenge of running a unified system. "I’m definitely on board with the discussion on governance," he said, "but simultaneous with that, we’ve got to do what we can within our own structures, within our own planning, within our own frameworks, to be able to do what needs to be done to make the investments for state of good repair."

The MTA itself has had a hard time handling rivalries between its different divisions. "It is probably the most minefield-ridden area to deal with," said Prendergast. "We have a governance structure that has existed since 1978. It’s fairly successful, but it’s got its own challenges within our own family. And I know how difficult it is to change governance within our own families, so when we transition out of our agencies, and other agencies, across state lines, it gets very very difficult."