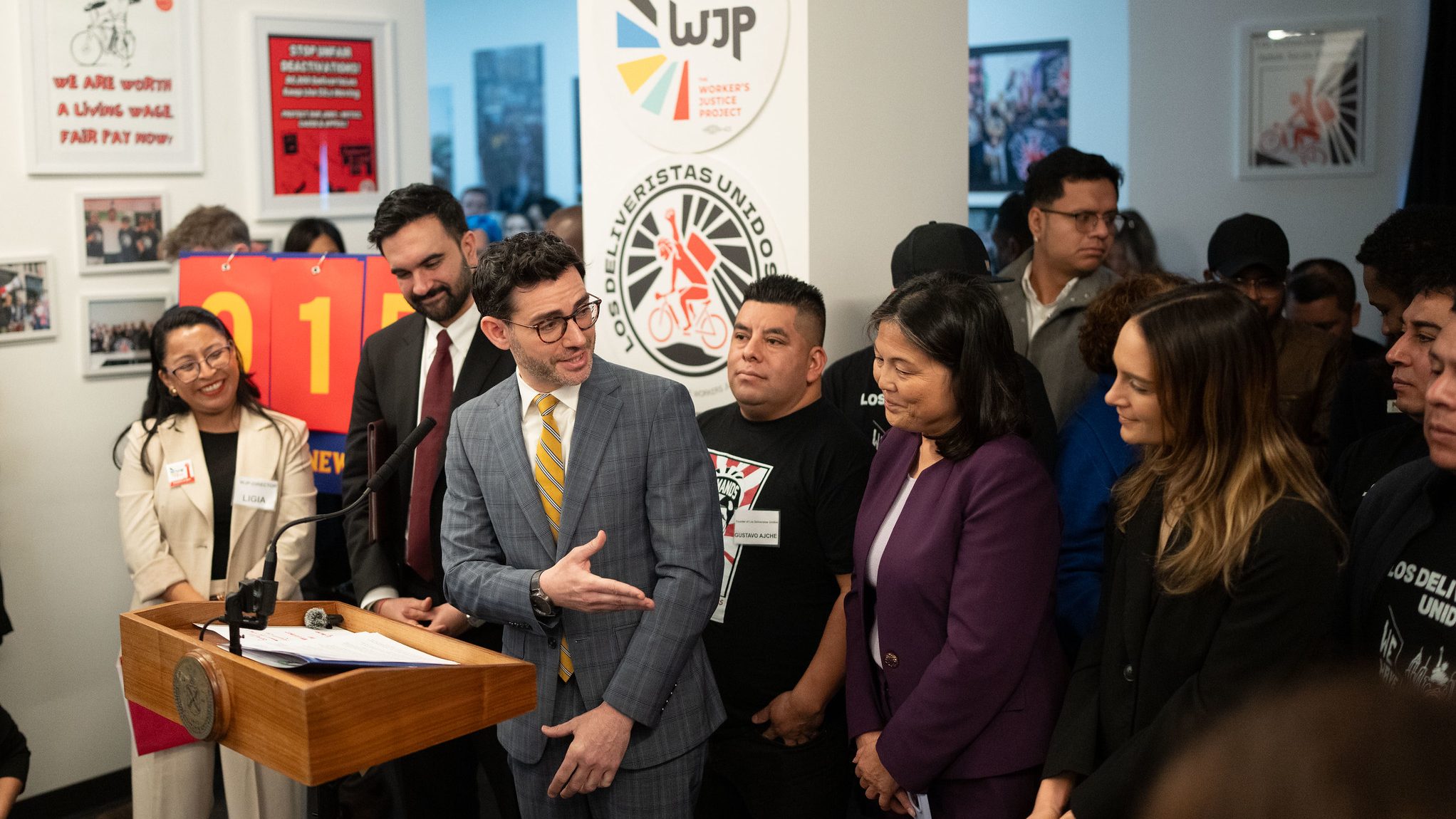

A plan to calm traffic on a speeding-plagued stretch of Riverside Drive in West Harlem would be gutted if Community Board 9 members get their way, but Council Member Mark Levine, who represents the area, wants DOT to move ahead with the safety plan.

“It's all really sensible stuff that’s been succeeding in other parts of this district and this city,” Levine said. “I certainly value all the community input, and it needs to go through all the steps on the community board, but... I think DOT should move forward.”

The proposal features a mix of curb extensions and pedestrian islands on Riverside Drive between 116th and 135th Streets. Between 2008 and 2012, there were 20 serious injuries on this stretch of Riverside, including one pedestrian and 19 motor vehicle occupants [PDF].

The most dangerous section, according to DOT project manager Dan Wagner, is the Riverside Drive viaduct, which runs from just north of the General Grant National Memorial to 135th Street.

The average speed on the viaduct is 36.5 mph, according to DOT, with 79 percent of drivers clocking in above the posted 30 mph limit. In December, Levine and fellow Council Member Helen Rosenthal asked DOT to bring Riverside's speed limit in line with the citywide 25 mph default [PDF].

DOT says it will do that, but only if the street is also redesigned to reduce speeds. Under the agency's proposal, the viaduct from the Grant Memorial to 135th Street would be slimmed from two lanes in each direction to one, with the remaining space used for wide striped buffers. (Though Riverside is already a busy cycling route, DOT has refused to propose bike lanes.)

The road diet also creates space for new sidewalks and crossings near bus stops at the north end of the Grant Memorial. If two lanes are retained over the viaduct, DOT says there will not be enough room for the pedestrian space.

Last night, the Manhattan Community Board 9 transportation committee held its third meeting about the project. As before, board members and some residents argued that the street should retain its speedway design, or else drivers who use Riverside as an alternative to the West Side Highway will cause traffic jams and pollution.

DOT says its traffic models show the redesigned viaduct would be able to handle the traffic without leading to more congestion, but nothing could convince opponents last night. "I just find it hard to believe that you won’t have more congestion," said CB 9 member Victor Edwards, who complained that a road diet on St. Nicholas Avenue had slowed down his car trips between 125th and 155th Streets.

The committee did not vote on a resolution last night, but took a poll of members and meeting attendees on the project's various components. The road diet failed to gain majority support, as did DOT's plan for 120th Street. There, the agency is proposing four pedestrian islands, with eight new trees, as part of a road diet between Riverside and Broadway.

Instead, CB 9 member Ted Kovaleff argued to scrap the pedestrian islands for back-in angled parking, and after lots of confusion over what was up for a vote and who was voting, he got a majority of board members in the room to go along with him. Kovaleff is the same CB 9 member who said last month that Riverside Drive should remain a cut-through route with no road diet.

The results of the vote will inform CB 9's draft resolution on the proposal. “This is democracy in action. This is what community boards are all about," Kovaleff told the audience as the meeting was being adjourned. "I hope that some of you seeing this say, 'Hey, I want to get involved even more.'"

Levine, an elected official who helps appoint community board members, supported the 120th Street pedestrian islands. "This is a pedestrian district," he said. "If you had the angled parking, you would lose all the safety features that DOT is proposing for pedestrians, and frankly I would expect that adding more parking there would further snarl traffic."

Levine also strongly backed the Riverside Drive road diet. “It’s not intended to be an alternative commuting route to the highway. This is a local street for us,” he said. “To the extent that we can calm traffic some, I think it will change people’s commuting patterns and they'll stay on the highway... That would mean fewer cars, and lesser amounts of fumes in an area with high asthma.”

“It’s a little counter-intuitive," Levine said of road diets. "You are actually going to smooth the movement of traffic. Now, it might be a little bit slower, but we want people to adhere to the speed limit. And [right now] they’re not coming anything close to that."