The Law Office of Vaccaro & White is representing the victim in what may be the first case of a precinct-level charge for violating NYC Administrative Code Section 19-190, also known as the Right-of-Way Law.

The Right-of-Way Law provides for criminal misdemeanor penalties for a driver who strikes and injures a pedestrian or cyclist with the right of way. The law was designed to allow precinct-level officers to charge sober but reckless drivers who stay at the scene -- something that for years, only a tiny, specialized group of officers assigned to the NYPD Collision Investigation Squad were permitted to do in a handful of the most serious cases.

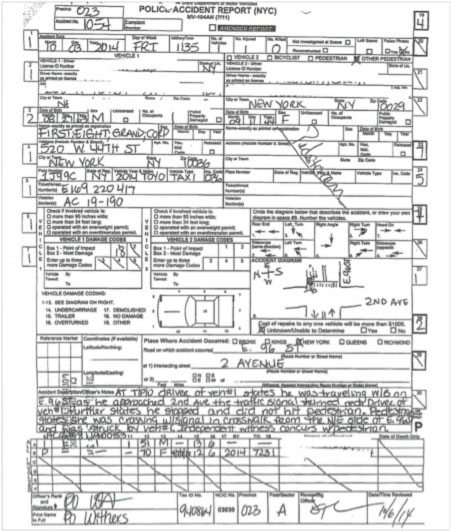

The crash involved a 70-year-old woman attempting to cross East 96th Street from north to south at the eastern leg of the intersection with Second Avenue, walking from home to the Stanley Isaacs Senior Center. A cab driver who was proceeding westbound on East 96th Street ran a red light and struck her in the crosswalk while she had the walk signal. The victim suffered serious but not life-threatening injuries. The cab driver admitted that his light was red, but claimed that he obeyed the red light and never made contact with the woman. According to the report, the police officer from the 23rd Precinct responding to the crash interviewed an "independent witness" at the scene, concluded that the driver’s account was false, and charged the driver with violation of the Right-of-Way Law.

The charge is significant because it may reflect an end to NYPD's "observed violation" rule, which prevents precinct cops from issuing citations for motorist violations they do not personally witness, as well as other limits on precinct-level investigation and enforcement against reckless driving.

NYPD crash investigations have until now proceeded along one of two tracks. Only the worst crashes -- causing fatalities and critical injuries -- are investigated by a 20-member Collision Investigation Squad (CIS), while the other 90 percent of serious crashes are investigated by precinct-level officers.

Under this two-track system, CIS officers can interview witnesses, gather videotape and other forensic evidence, and issue charges against sober drivers who stay at the scene. In contrast, precinct officers responding to non-life-threatening crashes are not permitted to issue summonses for reckless acts not observed by police -- in keeping with the so-called “observed violation” rule -- and often ignore criminality other than DWI offenses, even hit-and-run cases.

The Right-of-Way Law was designed to remove the limits on precinct-level traffic crash investigation and enforcement and to make precinct officers, who respond to 90 percent of serious crashes, the vanguard for street safety. Two features of the Right-of-Way Law make this possible. First, by defining a driver’s violation of a pedestrian or cyclists’ right of way as a misdemeanor -- a crime -- instead of a traffic violation, the law eliminates application of the “observed violation” rule (which apparently only applies to traffic violations). Officers no longer have to randomly observe a traffic violation that causes injury in order to take enforcement action against it.

Second, the Right-of-Way Law allows a criminal charge based only on evidence of specified conduct, rather than requiring proof of the driver’s recklessness or intention to do harm. This feature of the law bridges a critical gap between two types of criminal laws: conduct-based laws, such as DWI and fleeing the scene of a crash, and culpability-based laws, such as reckless endangerment and criminally negligent homicide. Guilt under conduct-based laws is proven with evidence that a driver unjustifiably engaged in certain specified conduct, while guilt under culpability-based laws requires proof that the driver was subjectively aware of the risks he or she created, or was otherwise "morally blameworthy."

In the case of the woman who was hit crossing 96th Street, a precinct-level officer was able to charge a driver for violating the Right-of-Way Law based on reliable evidence that the driver struck a pedestrian with the right of way, without inquiry into the driver’s mental state.

This is exactly the type of enforcement action that proponents of the Right-of-Way Law sought. NYPD has been remarkably tight-lipped about enforcement of the law, refusing to publicly state whether precinct officers would receive any training or information after it took effect on August 22. This instance suggests that precinct-level officers have been notified of the Right-of-Way Law and given guidance in its use by NYPD.

The statement in the MV104 report that “independent witness concurs with pedestrian” is striking and bespeaks a critical, investigative type of inquiry by the officer, rather than the uncritical and passive “report what you see and hear” narratives more typical of such reports. The officer responsible deserves praise from safe streets advocates, and officers in other precincts should be encouraged to follow this promising example.