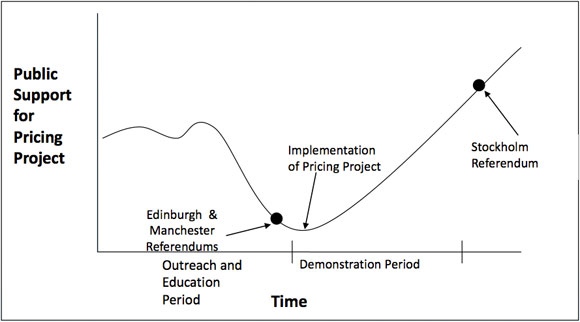

Last week, Columbia University professor David King ran a great response to the recent grousing about bike-share stations. He posted this graph depicting how public perceptions of congestion pricing programs change over time.

An outfit called CURACAO (one of the weirdest, most tortured acronyms of all time -- it's short for "coordination of urban road-user charging organisational issues") spent years analyzing various road-pricing attempts in Europe, including shifts in public opinion. This graph of theirs shows that the more people learn about congestion pricing, the more people feel vested in opposing it, and the less popular it becomes -- until it's implemented, after which everyone can see that it works, it becomes the new normal, and popularity climbs.

In Edinburgh and Manchester, voters rejected congestion pricing in referendums before they had a chance to see it in action. Stockholm did it differently, holding a six-month congestion pricing demonstration before asking residents to vote. Having seen the results of road pricing, voters decided to make it permanent.

Transpose this pattern to NYC street redesigns, and it's all the more impressive that the city manages to make changes, given the current community board process. DOT's toolkit now includes materials that make possible inexpensive, temporary changes -- demonstration projects, basically -- but community boards are always asked to vote before any demonstration can be implemented. Vote after vote in favor of pedestrian safety upgrades, protected bike lanes, and bus lanes happened at the point of maximum resistance on this curve. Now imagine if all CB votes happened after a six-month demonstration.

With regard to bike-share and the impending launch on Monday, I doubt the NIMBY noise about station placement signifies a broad drop in public support for the program, which consistently polls in the range of 70 percent approval. But we are at the point of maximum tabloid coverage, maximum litigation, and maximum resistance, such as it is. And in the long run, I think it's fantastic that the NYC press corps is recording all these complaints for posterity. When bike-share reaches the point where it's just a nice part of life in New York City, let's not forget all the screaming headlines from spring 2013. They're the proof that no matter how worthwhile or popular a given transportation reform might be, you have to overcome some resistance first.

There have been plenty of examples of this during Janette Sadik-Khan's tenure at NYC DOT. Remember the moaning about Fordham Road Select Bus Service, the Eighth Avenue protected bike lane, or the Times Square plazas? In the end those all turned out to be welcome, effective changes that worked well for local businesses.

Bike-share is on a whole other scale -- it's freaking huge, and while it doesn't cover nearly the whole city, New York's political and media elite are going to see these bikes every day. If they all remember the media uproar of the pre-implementation period after the dust settles, that could help other street redesigns and transportation reforms move forward in the future.

The next mayor could do so much to make city streets safer and more useful for New Yorkers -- converting car-clogged arterial roads into transit boulevards, ramping up the Slow Zone program to cover many more neighborhoods, expanding the protected bike lane network into Queens and the Bronx. Whoever wins the election should remember what happened with bike-share. People are going to complain about process. People will sue. The tabloids will bluster. And it will be totally worth it.

Enjoy the long weekend, Streetsblog readers, but come back here on Monday. We'll have a bunch of Citi Bike coverage for you.